Long-range forecasts: how are climate outlooks made?

16 August 2018

Climate outlooks, also called long-range forecasts, tell us which way our weather will lean over the coming months or seasons: Wetter or drier than usual, hotter or colder, or no strong push either way. So, what information goes into them and how are they made?

Climate outlooks can be powerful tools to help you make decisions on activities affected by weather variability—from workforce planning and agricultural methods, to severe weather season preparation or even when to take a holiday.

They work because weather isn’t simply random. Weather is driven by the energy from the sun and by the transfer of energy, mass and momentum between the oceans, atmosphere, ice and land—and all this occurring on a spinning, tilted planet.

In the past, climate outlooks used relationships between the bigger climate drivers, such as El Niño and La Niña, and the average weather for a region at a given time of year. As a blunt instrument for broad areas, that did pretty well—certainly better than pure guesswork. But we now have the climate science and computing technology to calculate a Climate Outlook based on the current state of the oceans, atmosphere, land and ice, and how they are likely to interact and evolve with time.

Gathering the data

Every day the Bureau collects around 40 million observations, from ground stations and ocean buoys to weather balloons, aircraft and satellites. These observations cover every corner of the globe and allow us to create a highly detailed three-dimensional view of the current state of the Earth's environment.

Image: Our observation network gathers information from a vast array of equipment operating from under the sea through to space.

Our long-range forecast computer model places this huge amount of data into a three-dimensional grid, then uses mathematical relationships that represent the physics of oceans, land, ice and atmosphere, and their interactions, to calculate how each value could change over the next few months. Think of it as taking the conditions we can measure on the globe today, placing them onto a separate but identical world, then fast-forwarding a few months.

Many possible futures

When we look several months ahead, there is a lot of chance for apparently random changes in the weather to occur. This means the weather over the next few months isn't preordained—there are several very real possibilities.

Image: A long-range forecast model is like creating a second Earth, one which we can perform experiments on to see what weather could occur in the months ahead

Using a model Earth means we can test what these future states may be. We do this by making small changes to the initial conditions (the observations) that we feed into the model—these changes represent our uncertainty in the observations. For example, we might run the forecast model 100 times, with slightly different initial conditions each time. The 100 different scenarios that this would generate are called an 'ensemble', with 100 'ensemble members'. If, say, 80 of these 100 outlooks predicted wetter-than-average conditions developing in an area, we say the likelihood of a wetter-than-average season in this location is 80 per cent. If only 50 of the outlooks turn out wetter than average, we give a 50 per cent chance.

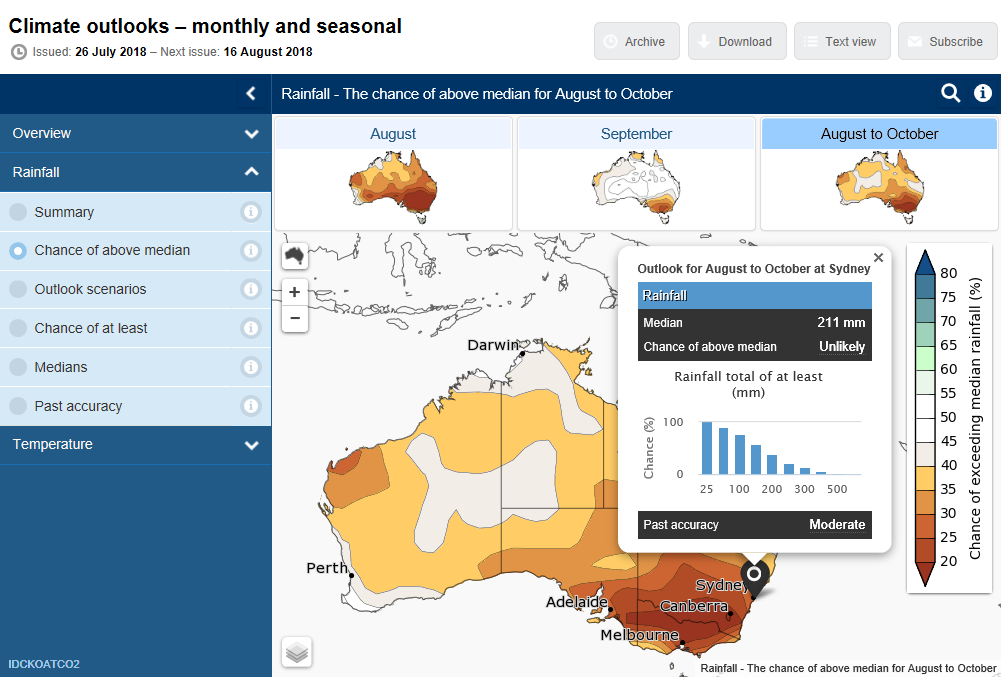

Image: Climate Outlooks website showing the chance of above median rainfall

Testing the model

To test the reliability of our model, we run it over a period in the past—usually about 30 years. We compare the historical outlooks from those runs ('hindcasts') with what actually happened. Since some climate events (such as La Niña or El Niño) don't occur each year, we use as long a period as we can to test how the model would behave in different situations. We're somewhat limited, because the detailed ocean observations we need to start the forecasts are only available for the recent past.

Just like our outlooks, we also run ensembles for our hindcasts. Having multiple start dates with multiple ensemble members over many years generates a lot of data—of the order of tens of thousands of model years—enough for us to be confident the model works

Since we are doing so many calculations and generating such a huge amount of data, our long-range forecast model runs on one of the most powerful supercomputers in the southern hemisphere.

Turning data into outlooks

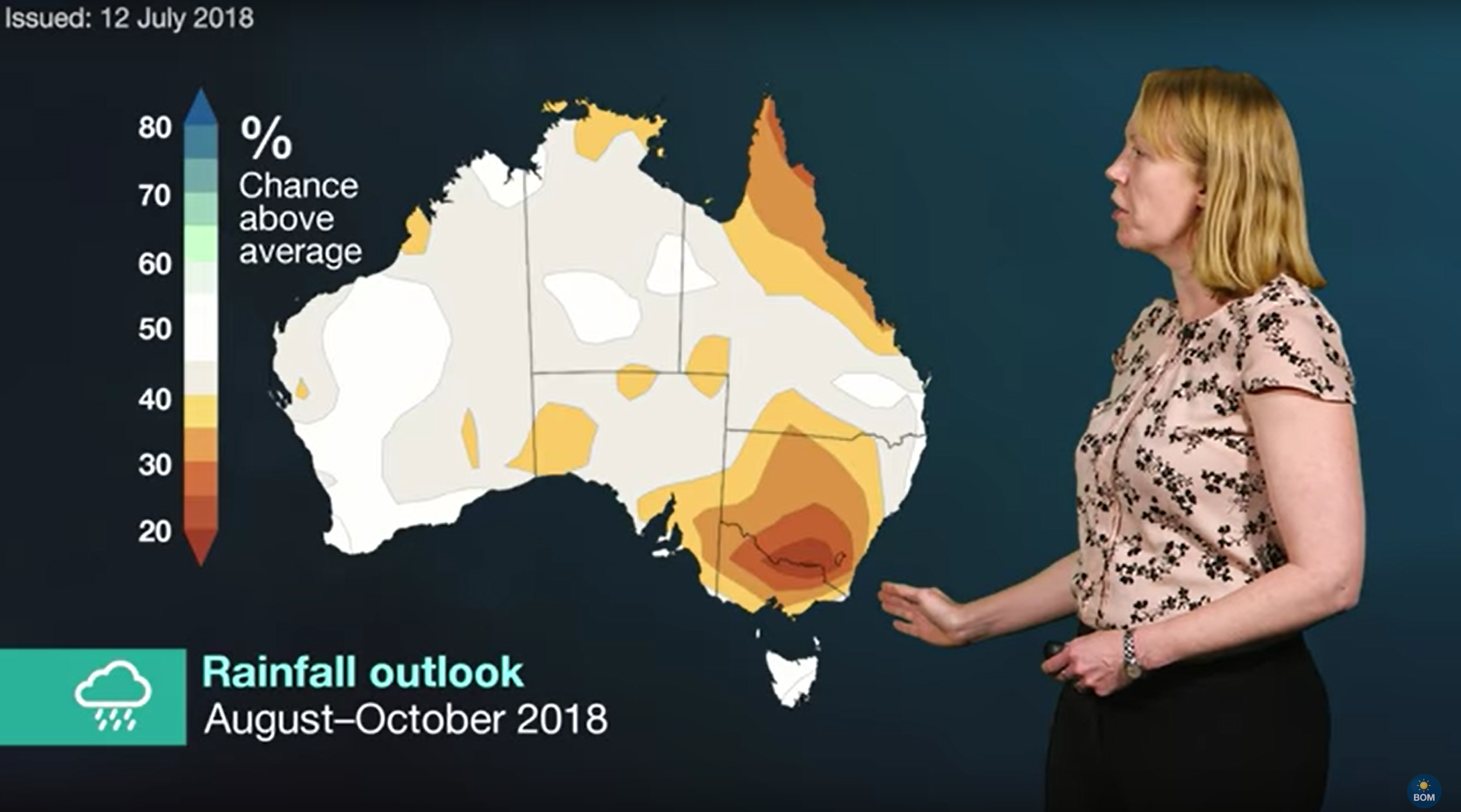

To understand and explain the outlooks, our climatologists interpret all this data and transform it into useful information. Effectively, they pull apart the model information to determine what is driving the outlook and, by combining this with their knowledge of how the model works, create a picture of the broad drivers of our climate and how much confidence we should have in the outlook. It's then their job to present that information to the community—online, on TV and radio, in print, and in person.

So next time you're wondering 'When's it going to rain?', have a look to the heavens for a satellite, think about a century of climate science, consider 1015 calculations being done every second for months on end on a supercomputer, and marvel at how much science and technology goes into that 'chance of above-average rainfall'.

Image: Our outlook videos explain the long-range forecast for the upcoming three months.

More information

Check out the latest Climate Outlook and subscribe to future editions.

What to expect from the climate when the outlooks are neutral

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.