Hands across the ocean: How global collaboration has transformed our tsunami warnings

22 December 2014

A decade after the Indian Ocean Tsunami caused one of the greatest natural disasters of our time, the Bureau of Meteorology and Geoscience Australia are providing the technological backbone of one of the world’s most advanced tsunami warning systems.

There can be few adults on the planet who do not remember the tragic events of December 26th 2004. That day, 10 years ago, should have been a time of peace and celebration for communities around the world. Instead, it is seared into our collective memory as the day that a series of colossal waves swept across the Indian Ocean – swallowing entire towns, claiming more than 230,000 lives, and displacing 1.6 million people in a terrifying surge of overpowering water.

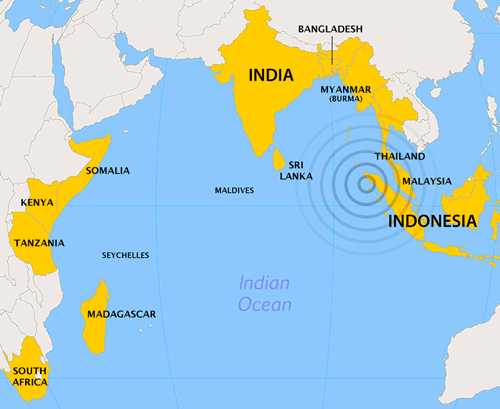

If one lesson came from the 2004 tsunami, it was of the overriding importance of knowledge. From its devastating impact within minutes in the Indonesian province of Aceh, where it cost more than 130,000 lives, the ‘wave train’ took at least 1.5 hours to reach the shores of Thailand, India and Sri Lanka – where 50,000 more lives were lost. After a further 10-12 hours, travelling at speeds of up to 900 km/h, the tsunami had crossed the Indian Ocean, claiming further lives in Kenya and Somalia.

It was clear, early on, that thousands of people could have been saved with a simple system of advance warnings.

Before 2004, the risk of a tsunami occurring in the Indian Ocean had been considered relatively low by many, and most countries had no tsunami warning system in place. Although Australian scientists and emergency managers were aware of the risk, the region had limited seismic information to quickly analyse earthquakes, and almost no real-time sea-level information to verify and monitor tsunamis. With no tsunami warning centres or national contacts to inform them of an impending threat, coastal communities were completely unaware of the risk of tsunamis – and utterly unprepared to respond.

Australia was one of the countries for which the 2004 tsunami served as a powerful wakeup call. While no lives were lost here, as most of the tsunami energy had travelled westward, 30-40 people had to be rescued from dangerous surf conditions along the Western Australia coast. As one of Indonesia’s closest neighbours, Australia was among the first nations to respond to the unfolding humanitarian crisis. It also quickly emerged as a key player in the scientific response to the tragedy – the clear and urgent need to develop a unified tsunami monitoring and warning system for the Indian Ocean basin.

At the Bureau of Meteorology, there had been a basic tsunami alert system in place for several years, although this system was largely focused on threats emanating from the Pacific, where Australia had been an active member of the Pacific Tsunami Warning System since 1965. Dr Ray Canterford, now the Bureau’s Deputy Director of Hazards, Warnings and Forecasts, was the national contact for this system – and as a result, was thrust into the whirl of urgent diplomatic activity that followed the 2004 tsunami.

“It was very emotional, but also very inspiring how quickly everyone mobilised,” recalls Dr Canterford. “I’ve been involved in international work for over 30 years, and I’ve never seen anything like this in terms of countries coming together and supporting each other.”

By the end of January 2005, a series of ministerial and regional meetings had ratified the urgent need for a regional tsunami network uniting the 28 countries of the Indian Ocean basin. In Australia, work began in earnest to establish a world-class tsunami warning system. This would not only provide advice on any tsunamis generated by the tectonic fault lines surrounding Australia that could impact our coastal communities, but a suite of technology and expertise that could assist countries across the Indian and Pacific oceans to strengthen their warning systems.

Over the next four years, Dr Canterford and his counterpart at Geoscience Australia, handpicked a team of technical and warning experts to develop a robust real-time network of ocean-monitoring instruments, seismic stations, and numerical tsunami forecast models with the goal of providing at least 90 minutes’ warning of any potential tsunami impact on Australia’s coastline.

“Several government agencies, including the Bureau of Meteorology, Geoscience Australia, the Attorney General’s Department and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade worked together to achieve the goal of a world class tsunami warning system,” said Dr Canterford.

JATWC was officially launched in 2008, and three years later – together with India and Indonesia – providing tsunami threat information for the entire region.

Understanding the risks

The Indian Ocean Tsunami was caused by a major undersea ‘megathrust earthquake’ centred off northwest Sumatra, at the northern end of the Sunda Trench, a deep-sea trench where the major Indo-Australian tectonic plate slides or ‘subducts’ under the Andaman plate.

Although it was a rare event seismologically in terms of its size and location – the magnitude 9.1 quake was not unique. The tectonic plates in this area have been pushing against each other and building pressure for thousands of years. Such pressures continue to build along all subduction zones where tectonic plates collide, including the ‘Ring of Fire’ which circles the Pacific Ocean. The pressure is from time to time released, when one of the plate edges buckles up. This deformation of the sea floor (which in 2004 created a permanent cliff up to 10 metres high and 1,200 km long) displaces the water above it, creating a tsunami. Many scientists believe the further release of such pressures will cause another significant tsunami in future.

Although the Sunda Trench and the Puysegur Trench off New Zealand are arguably the most active fault lines around Australia, we are surrounded by more than 8,000 km of fault lines, including the Solomon-New Hebrides Trench to the northeast and the Kermadec-Tonga Trench to the east. Since 2004, several other major earthquakes – in Java in July 2006, Samoa in September 2009, Chile in February 2010, the Mentawai Islands in October 2010, Japan in March 2011, Bali in October 2011, Sumatra in April 2012, and the Solomon Islands in February 2013 – have all served as reminders of our continuing vulnerability.

Animation showing modelling of wave height dissemination during the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Credit: Geoscience Australia

Tsunami warning network

The Bureau’s tsunami warning services are based on three separate pieces of technology, each highly specialised in its own right. The first is a network of six deep-ocean tsunami detection buoys, which provide the backbone of the agency’s ocean monitoring – and a critical part of global monitoring in the Indian and Pacific oceans. The buoys are located in pairs (to provide immediate backup) in three sites that are particularly prone to earthquakes: two in the Indian Ocean, close to the Sunda Trench; two in the Coral Sea, on the edge of the Pacific Plate; and two in the south Tasman Sea, close to the Puysegur Trench.

Although the buoys are extremely accurate, each costs more than $1 million to build and deploy. Their exposure to heavy weather provides significant maintenance costs for the Bureau. However, they are a critical part of Australia’s tsunami infrastructure: providing instant alerts and verification of sea-level changes caused by tsunamis that are unnoticeable on the surface in the deep ocean, by measuring changes in sea levels as small as 1 mm. (It is only in shallow water that tsunami waves slow down and grow to threatening heights.)

The Bureau also maintains a vast network of tide gauges attached to coastal piers and jetties, with 43 gauges currently operating around Australia, our offshore islands, and in our 14 partner countries in the Pacific. Data from both the gauges and buoys is updated every minute through JATWC’s phone and satellite network, and added to real-time data servers linking hundreds of other gauges and buoys across the world’s oceans, and exchanged freely in real-time between countries.

The Bureau’s third technology is the sophisticated computer modelling software that holds the key to predicting tsunami threats and determining the need for any warnings. This is performed on a powerful supercomputer at the Bureau that uses data on the location, depth and magnitude of earthquakes to simulate how much water could be displaced by the seafloor – and in which direction it is likely to travel.

Animation showing monitoring, detection, analysis and warning of the Australian Tsunami Warning System. Credit: Geoscience Australia

Time to save lives

While Australia is very close to the Pacific ‘Ring of Fire’ – the source of 75% of the world’s volcanoes, and 80% of its major earthquakes – we occupy a very stable location in the middle of a continental plate, away from major fault lines. Despite our geological stability, however, tsunamis generated by earthquakes in the Pacific or Indian oceans have the capacity to approach our coastlines at the speed of a jetliner – taking as little as two hours to reach the Australian mainland or Tasmania. This is the vital ‘window’ within which JATWC must determine their threat and issue the warnings that underpin our communities’ and emergency services’ response.

When Geoscience Australia registers an undersea earthquake of magnitude 6.5 or above through its world-class monitoring of global seismic data, its objective is to let the Bureau know within 10 minutes of the earthquake occurring. The Bureau then combs through its database of pre-computed tsunami simulations to find the best match to GA’s seismic and locational data, from which it assesses the potential of a tsunami threat to Australia and countries across the Indian Ocean. (The speed and precision of the Bureau’s supercomputer enables it to create a vast database of tsunami scenarios from all possible undersea earthquake sources around the globe.)

JATWC’s goal is to provide tsunami warnings within 30 minutes of any magnitude 6.5+ undersea earthquake occurring anywhere in the world, providing Australians with at least 90 minutes’ warning of any threat – as well as critical information for Indian Ocean countries, and valuable data for the Pacific Ocean system.

Most earthquakes pose no tsunami threat to Australia, and JATWC will issue a National No-Threat Bulletin when it assesses the threat to be either non-existent or negligible. On average, JATWC has been issuing No-Threat Bulletins about once a week, reassuring Australians that we are fully aware of large earthquakes happening around the world – but they pose no tsunami threat to us.

If the model does indicate a potential threat, JATWC will immediately issue a Tsunami Watch for relevant areas. It will then monitor its ocean and coastal networks to see if a tsunami has developed, how dangerous it is, and where it is heading. If a tsunami is confirmed or the threat is within 90 minutes of Australia, the Watch will be upgraded to a Tsunami Warning – repeatedly reissued on an hourly basis or updated when new information is available – detailing which coastal zones are under what specific level of risk.

There are two categories of tsunami threat: a Marine Threat for dangerous ocean conditions such as strong currents and surges, when people should get out of the water and move away from the water’s edge, but do not need to evacuate; and a Land Threat, when low-lying coastal areas may be inundated, and people should move at least 1 km inland or to ground at least 10 metres above sea level.

As soon as JATWC confirms the existence of a tsunami threat, the Bureau will give the relevant emergency authorities a ‘heads-up’ call before specific warnings are issued. It also liaises closely with national and regional media to ensure that the public receives timely warnings on radio and TV, as well as via the Bureau’s website and a dedicated tsunami hotline (1300 TSUNAMI). The warnings are also delivered to a number of other relevant authorities and organisations, such as port and maritime authorities, the Department of Defence, Surf Life Saving Australia, and the Australian Maritime Safety Authority. JATWC also provides its tsunami threat advices for all Indian Ocean coastlines to national tsunami warning centres across the ocean basin.

“Australia has played a major role in building the Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System, and it’s something we can all be proud of,” says Dr Canterford. “I will never forget standing on the beach in Phuket four weeks after the 2004 tsunami, among all the memorials and that total, terrible devastation.

“We must never forget that dreadful day, and we must always maintain our commitment and our vigilance to ensure that if such a tragedy happens again, we have the best possible systems, based on rigorous international collaboration and efficient, well-managed warning systems, to minimise the loss of life as far as we possibly can.”

Further information

Further information on JATWC and the Australian Tsunami Warning System can be found at:

http://www.bom.gov.au/tsunami/index.shtml

https://www.emknowledge.gov.au/connect/tsunami-the-ultimate-guide/#/

Scientists at the Bureau’s National Tidal Centre have also prepared an animation to illustrate how the 2004 tsunami travelled around the world’s ocean basins: http://www.bom.gov.au/tsunami/info/media/sumatra_plan_topog.avi

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.