The big chill: what is a cold front?

11 July 2016

A cold front is a feature we see every day on weather maps, particularly through southern parts of Australia. So what are they, and should you put your outdoor activities on ice when one is heading your way?

The cold front shirtfront

Cold fronts can pack a powerful punch. In 2014 a sequence of strong cold fronts crossed southeast Australia between 22 and 29 June, bringing squalls and gusts in excess of 90km/h across many areas. In Melbourne and surrounding bayside suburbs the associated low pressure system caused a storm surge, large waves and tidal flooding. Flooding in bayside suburbs and along the Yarra River caused significant disruption to transport, as well as widespread coastal erosion.

Extensive storm damage was reported in Victoria, New South Wales and South Australia. In Victoria, more than 80 000 properties lost power and two deaths were associated with collapsed walls. Heavy rainfall later in the event led to flash flooding in northern Tasmania. Substantial snowfall was reported in the alpine regions of New South Wales and Victoria, elevated regions of Tasmania and the highest peaks of South Australia’s Mount Lofty Ranges during this event.

While not all cold fronts produce such damaging impacts, abrupt changes in temperature, wind speed and direction, and rainfall are common features of cold fronts anywhere in Australia.

Waves crash across Kerford Road Pier in Albert Park, Melbourne, 24 June 2014, driven by the passage of destructive cold fronts. Photograph: Liam Edleston.

The cold, hard facts

A cold front is the leading edge of a relatively cold air mass moving into a region of warmer air. In the Australian region, warm moist northerly winds often occur ahead of the cold front, while colder dry southerly winds typically follow behind the cold front.

As the surge of cold southerly air moves northward and meets the warm air moving southward, a large difference in air temperature occurs and may extend as a ‘line’ across hundreds or thousands of kilometres.

The biggest change in temperature occurs with the passage of the cold front, however this is not necessarily the coldest air. The coldest air may move over an area many hours after the frontal change, sometimes bringing snow in wintertime. In summer, cold fronts can see temperatures plunge by as much as 10–15°C within the first 30 minutes.

The air behind the front is colder, drier and denser (heavier) than the air preceding the front. This cold air pushes under the warm moist air lifting it higher in the atmosphere. This lifting can produce cloud, causing rain bands, showers or thunderstorms to form, generally within 100 kilometres of the front.

The surge of denser cooler air ‘squeezes’ the atmosphere ahead of it. This squeezing effect is like putting your finger over the end of a running garden hose; the water speeds up. The squeezing strengthens the wind ahead of the front.

A front also usually brings a significant change in wind direction. In Australia, this is typically from a northwesterly direction in the warm area ahead of the change, around to a southwesterly direction behind the change.

Winds and gusts strengthen the closer you get to the cold front, with the strongest winds just ahead of the front. Behind the front winds can remain strong and gusty for a period of time, making conditions particularly dangerous for mariners.

Cold fronts can also move very quickly. A fast moving front can cover 100km in an hour.

When do they occur?

Cold fronts occur all year around, but they have different impacts throughout the year. In summer, strong northwesterly winds ahead of the cold front can bring very hot, dry air from inland over southeast Australia, leading to extreme fire danger. The wind change with the front can rapidly change the direction of any fires, further increasing the danger.

In winter, the inland air is cooler, but damaging winds and heavy rainfall can occur with the passage of a strong front, while snow can develop behind the front in the coolest air.

Cold fronts are generally stronger in southern Australia during springtime when the Australian continent is starting to warm up but the sea to the south is still very cold.

Want to know if a cold front is heading your way?

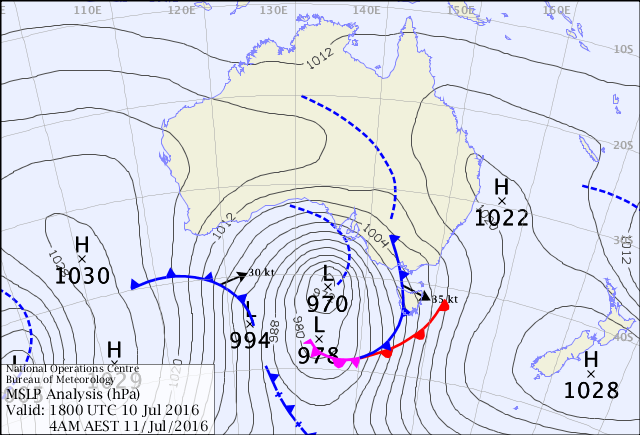

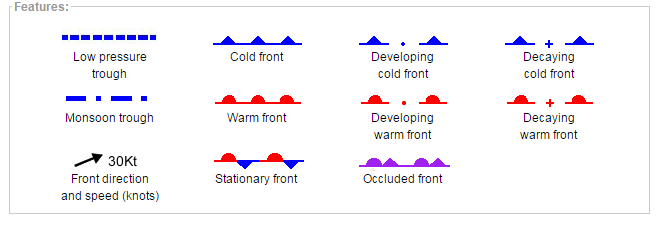

Look for yourself on our synoptic charts; a cold front is represented by a solid blue line with triangles along the front pointing towards the warmer air and in the direction of movement.

If a cold front is expected to bring potentially dangerous weather, the Bureau will issue a Severe Weather Warning. Check the latest weather warnings at www.bom.gov.au.

Mean Sea-Level Pressure Analysis 11 July 2016

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.