To Bourke and beyond: one scientist’s epic journey to 112 weather stations

18 August 2016

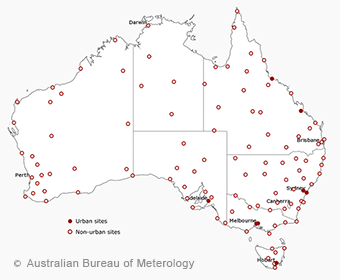

There are 112 weather observation stations that feed into Australia’s official long-term temperature record—and Bureau scientist, Blair Trewin, has made it his personal mission to visit all of them! Having travelled extensively across Australia—from Horn Island in the north to Cape Bruny in the south, Cape Moreton in the east to Carnarvon in the west—Blair has now ticked off all but 11 of those sites.

Map: the 112 observation locations that make up Australia's climate monitoring network

Some of the locations are in or near the major cities, but many are in relatively remote areas and can be difficult to access. Blair says perhaps his most adventurous site visit was on the 2009 trip at Kalumburu, an Aboriginal community on the northernmost tip of the Kimberley, and two days’ drive on a rough track from Broome. ‘I asked the locals the wrong question—they said I’d be able to get in, but I didn’t ask them whether I could get back out again’. After striking trouble at a creek crossing leaving town, he spent an unplanned week there waiting for his vehicle to be put on a barge back to Darwin.

While these locations are remote now, in some ways they were even more remote in the past. These days you can get a signal for your mobile phone in Birdsville, Queensland, but as recently as the 1980s, the only means of rapid communication was often-temperamental radio relays through the Royal Flying Doctor Service. Today distance is no longer an issue; the majority of weather stations in the Bureau’s climate monitoring network—including Birdsville—are automated, with thermometers that submit the information electronically.

Photo: Blair Trewin at the weather observation station at Tarcoola, in the far north of South Australia. The Stevenson screen houses a resistance temperature device (thermometer) and a relative humidity probe

But, even some of the sites closer to home have posed a challenge for Blair’s mission. To get to Gabo Island in Victoria for example, you need to either fly or take a boat, and the runway is just a few hundred metres long, so it can only be used in light winds. ‘I spent two days in Mallacoota waiting for the winds to drop enough to get over there’.

Similarly, the site at the Wilsons Promontory lighthouse, if you don’t use a helicopter, is accessed through a 37 km return hike, which Blair did as a training run with one of his Victorian orienteering teammates.

Blair has been a national-level orienteer for most of the past 25 years, which has taken him to parts of the country that are somewhat off the beaten track. Many of his site visits have been done during the course of orienteering trips, although more recently he has planned his travel with observation sites as a specific target, including a trip around Australia when he took long-service leave in 2009.

Photo: road sign along the Diamantina Developmental Road, which runs from Charleville in south-central Queensland to Mount Isa in the state's north-west

So why the fascination with visiting all 112 sites? Data from these stations are inputs to the Australian Climate Observations Reference Network – Surface Air Temperature (ACORN-SAT) dataset, which Blair played an essential role in developing. Combined, these stations hold over 100 years of records and allow scientists to better analyse long-term variations and trends in Australia’s climate.

However, Blair says seeing the sites in person sometimes has more than symbolic value. While the Bureau has extensive documentation about its sites—in databases and, for older information, on paper—some of the subtle influences on local climates are hard to appreciate without being there. ‘One example is at Cape Bruny in Tasmania, where we have two sites 50 m apart, one on the top of a hill and one just off to the side in a more sheltered location. Visiting there on a windy, showery, day made me appreciate how much more exposed the hilltop site is, and it turns out the hilltop site measures 17 per cent less rain than the more sheltered one, because some of the rain blows over the top of the gauge’.

Blair’s most recent trip was through a slice of previously unexplored territory in northwest New South Wales and western Queensland. ‘All the easy ones are done—the rest are in remote parts of Western Australia, the Northern Territory and northern Queensland’.

Photo: Road sign near Charleville, Queensland

Perhaps the most challenging site he is still to get to is Palmerville, in the remote interior of Cape York Peninsula. Located 80 km from the nearest significant road, it has one of the best long-term climate records in inland tropical Australia. ‘It was a late 19th century gold-mining settlement which became a ghost town, and for 40 years observations were made by the town’s last remaining resident, before an automatic station was installed in 2001’.

Blair isn’t quite sure when he will reach the remaining sites, but with in-depth knowledge of each station combined with orienteering skills, one thing’s for sure—he’ll be heading in the right direction.

For more information, including details of each weather station and a history of observations at the location, view the ACORN-SAT station catalogue.

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.