Subtropical ridge leaves us high and dry this June

06 July 2017

The first month of winter was very dry across most of Australia, causing concern for many farmers. So what's happened to our winter rain?

A dry start to winter

June 2017 was the second-driest on record for Australia and the driest June the nation has experienced since World War II. In large areas of southern Australia, including the entire State of Victoria, this was the driest June since national records began in 1900.

Image: Rainfall deciles across Australia for June 2017.

The dry weather brought very warm daytime temperatures to Australia. Southwest Western Australia experienced its warmest June days in over 100 years of records.

Image: Maximum temperature deciles across Australia for June 2017.

At the same time, parts of southeastern Australia were very cold at night and had frequent frosts. This has continued into July, with record-breaking overnight temperatures across Victoria and New South Wales.

Image: Minimum temperature deciles across Australia for June 2017.

High and dry

So what's behind this sunny, chilly and dry weather?

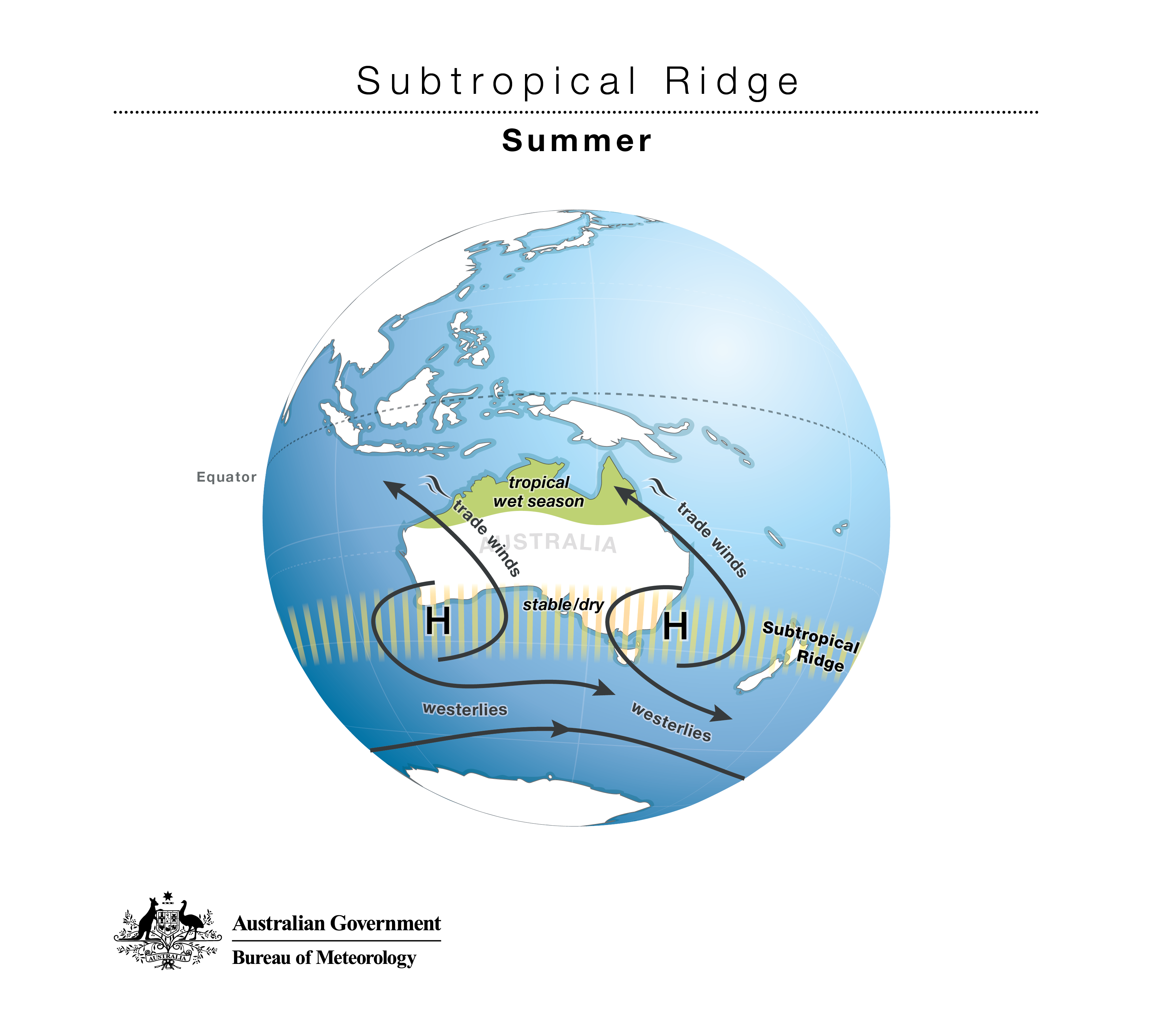

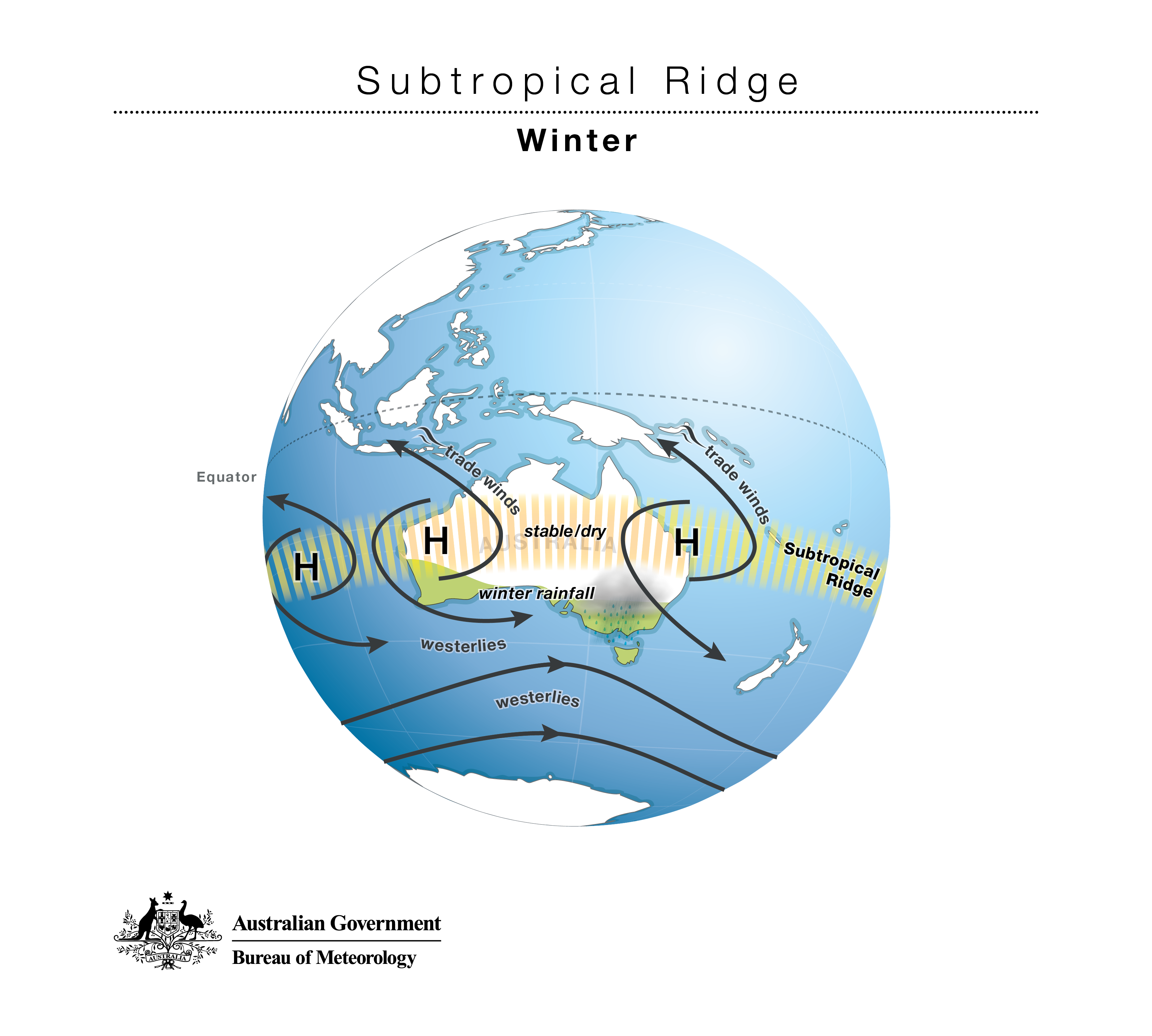

The subtropical ridge is a belt of high pressure systems that circles the southern hemisphere midlatitudes—the region of the globe between about 23°S and 66°S. It is a dominant influence on the climate of Australia. The belt of high pressure is associated with blue skies for the parts of the country that sit beneath it. During our summer it tends to sit over southern Australia, bringing generally dry weather. But in the winter it usually migrates north, allowing cold fronts and low pressure systems to move up from the Southern Ocean and bring rainfall to southern Australia.

Image: The subtropical ridge of high pressure over Australia usually moves north in the winter but has stayed down south this year.

This winter, that hasn't happened. Instead of a steady progression of rain-bearing fronts, southern Australia has seen high pressure system after high pressure system, bringing clear, dry days.

The subtropical ridge has remained firmly down south: it's currently sitting near Albury when it should be closer to Tamworth. Pressure across much of southern Australia is averaging more than 7 hPa above normal.

Not only is the subtropical ridge further south than it should be, but it's stronger as well: the strongest we've seen in June since 1944, which was the driest June on record for southern Australia. Almost all of South Australia and Victoria have recorded their highest June average pressure values on record, and some stations—such as Horsham and Mount Gambier—recorded their highest daily pressure values at any time of the year for at least 10 years.

The strength and location of the ridge means southern Australia has been missing out on the winter westerlies.

It's not all cut and dry

As well as dry weather across much of southern Australia, the lack of clouds associated with a strong subtropical ridge means warm days and frosty mornings. This has been very much the case for winter 2017 so far.

Image: Frost on the grass in Macleod, Victoria, June 2017. Credit: Catherine Ganter

Victoria had its coldest winter nights on record during 1944 and 1982, which were also its two driest winters on record. Both of these had an exceptionally strong subtropical ridge, although only one (1982) was also an El Niño year.

On the flip side, there is one area where a strong subtropical ridge can actually mean more rainfall: the east coast. In this region, a strengthening of the subtropical ridge and weaker westerly winds means an increase in the frequency of easterly onshore winds, which bring moist air from the Tasman Sea. June 2017 was a good example of this, with above-average rain along the coast from Sydney to Brisbane, while areas west of the Great Dividing Range were very dry.

The pressure is on

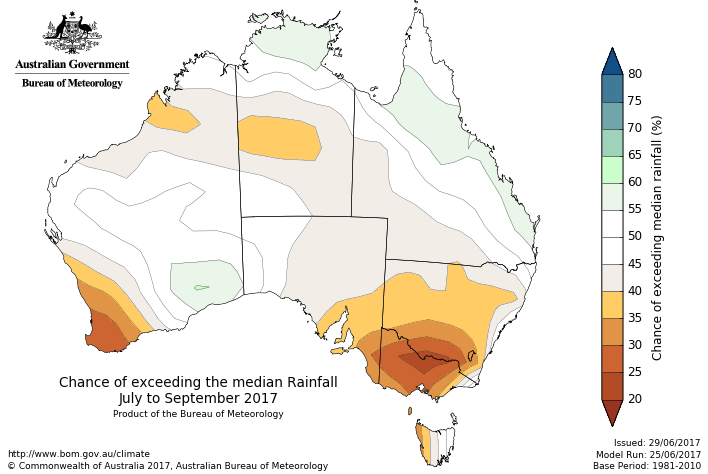

The Bureau's seasonal forecast models are suggesting very high pressure over southern Australia will continue for the next few months, and for those westerly winds to shift even further towards Antarctica and away from Australia.

Southward movement of the subtropical ridge is also related to a positive phase of the Southern Annular Mode (SAM), which refers to the poleward movement of the westerly winds across the whole southern hemisphere. The Bureau's models predict that SAM will be positive for much of July at least.

This means the dry conditions we've seen in southern Australia are likely to continue for the rest of the winter. While sunny days in winter sound lovely, this outlook has implications for many who look for winter rainfall in southern areas, like farmers, water managers and fire services.

The dry conditions and lack of fronts can also mean a lack of snow, although the cool nights are perfect for snowmaking and help the snow that falls to linger on the slopes.

Image: The outlook for July to September suggests dry conditions will continue in southern Australia.

Does this have anything to do with climate change?

It’s difficult to say how much of this year’s rainfall patterns are influenced by climate change, although early results suggest that climate change has increased the likelihood of dry Junes for Australia as a whole.

Rainfall in Australia is highly variable. There are a number of natural climate features which interact with each other to influence the subtropical ridge and rainfall more generally, including the El Niño–Southern Oscillation, the Southern Annular Mode and the Indian Ocean Dipole.

Climate change is also influencing rainfall over southern Australia. Research suggests that climate change is likely to be responsible for a 10–20 per cent decline in autumn and winter rainfall over southeast Australia in recent decades, and a 20–30 per cent decline in rainfall over southwest Western Australia.

While it is only one month, the pattern we have seen in June 2017 bears a striking resemblance to the characteristics of that rainfall trend. Indeed, the lack of rainfall in many southern areas due to a lack of fronts started earlier in autumn this year—June is just a continuation of this pattern.

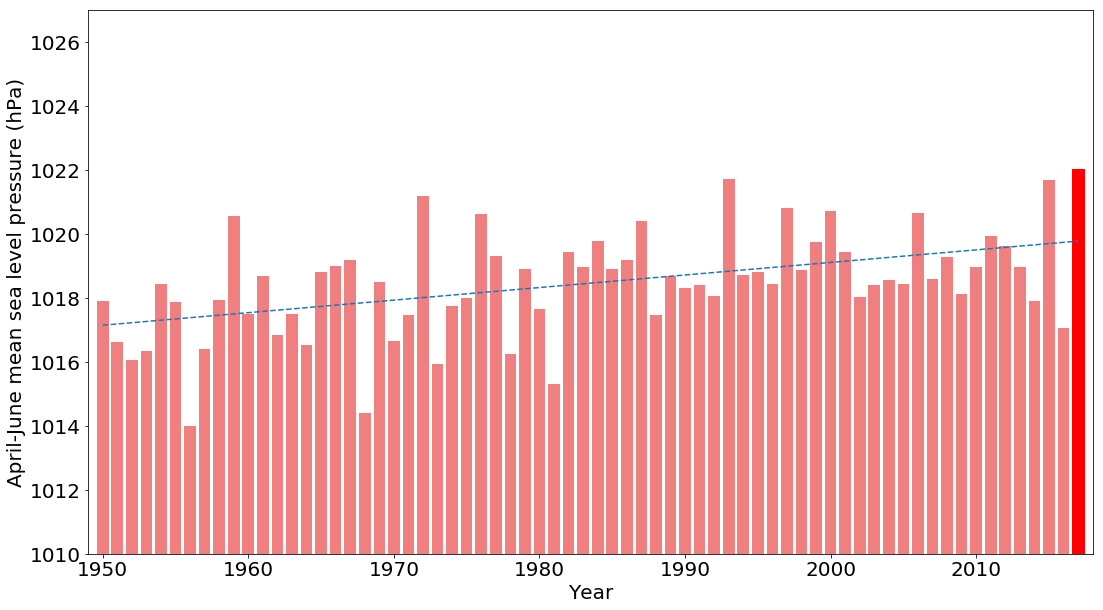

Image: Average mean sea level pressure over southern Australia from April to June, 1950 to 2017. Last month was the highest on record, almost 4 hPa above the long-term average. Data: NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis.

Global warming has seen an increase in the intensity of the subtropical ridge, as well as a more summer-like pattern of pressure year-round in southern Australia. This has been associated with a reduced influence of cold fronts and low pressure systems compared with the climate of the mid-20th century.

This pattern has also been associated with an expansion of the world’s tropical zones, which is pushing winter weather south while bringing increased tropical moisture during the summer months.

Natural drivers like La Niña and the Indian Ocean Dipole can still bring very wet years. Just last year we saw record-breaking rainfall in southern and inland Australia from May to September, associated with very warm sea surface temperatures to the northwest of Australia and a negative Indian Ocean Dipole.

But the background trend is reasonably clear. While our weather will continue to vary, dry Junes such as we have just seen are part of a broader pattern of higher pressure and less rainfall in much of southern Australia during the cooler months of the year.

More information

Explore climate outlooks for your region and sign up to receive our climate information emails.

Subscribe to this blog to receive an email alert when new articles are published.

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.