La Niña—but not as we know it

23 November 2017

The likelihood of a La Niña later this year is increasing. So what’s been going on in the tropical Pacific Ocean and what does it mean for Australia’s weather this summer? It might not be what you think, as a weak late-season La Niña can be quite different from those we’ve seen in the recent past.

Most climate models forecast the sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific Ocean will cool to La Niña levels during summer, but return to neutral values by March 2018—just long enough (around three months) to be declared an official event. So, we are looking likely to have a late, weak and short-lived La Niña—but it's unlikely to bring the widespread above-average rainfall to Australia that many of us have come to expect.

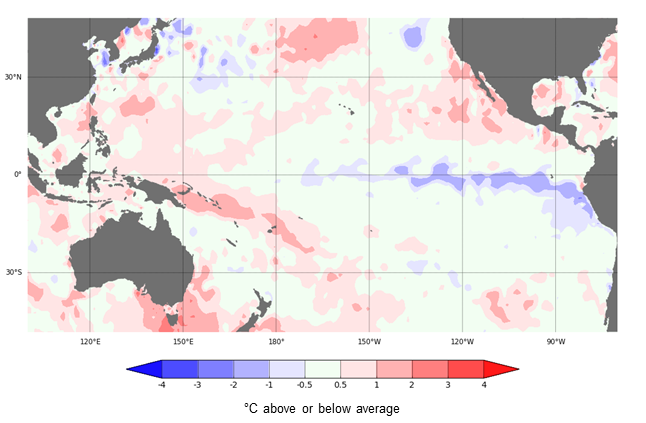

Map: Cooler-than-average sea surface temperatures in the eastern tropical (or equatorial) Pacific Ocean for the week ending 19 November—these are one of the indicators of La Niña.

What exactly is La Niña?

La Niña is one of the three phases of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO)—a recurring climate pattern that can influence Australia’s seasonal weather conditions. The others are El Niño, and a neutral, or normal, phase. Most of the time ENSO is in the neutral phase and doesn't impact our seasonal weather. But roughly every three to seven years it locks into the La Niña phase, typically for several months. This usually happens in late autumn or winter, and once the oceans and atmosphere enter a La Niña cycle, the pattern typically persists until the following autumn.

Usually, La Niña means above-average winter–spring rainfall for eastern and central Australia, and the early arrival of the monsoon across the tropical north. The extra cloud and rainfall over eastern and central Australia normally brings with it lower temperatures. La Niña also typically brings more tropical cyclones, more widespread flooding, and longer (but less intense) heatwaves.

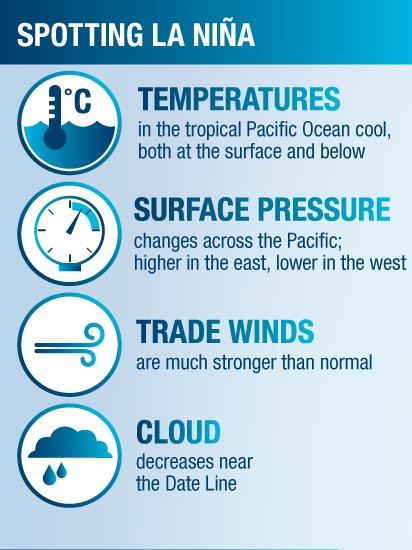

Image: The environmental indicators of La Niña.

What can we expect from a late-season La Niña?

Audio: Listen to Dr Andrew Watkins, manager of long-range forecasts, explaining the likely effects of a late-season La Niña on our summer weather.

Most La Niña events develop in the autumn or winter, with events starting in the last months of the year being rare. The most recent late-forming La Niña was 2008–09. That saw cooler and wetter conditions in November–December for many areas of eastern Australia, before turning dry in January–February, particularly in the southeast. Southern Australia had its third-warmest January–February since records began in 1910.

While no two La Niña events are ever exactly the same, the Bureau's three-month rainfall outlook for summer 2017–18 also doesn’t show a typical La Niña rainfall or temperature pattern. The rainfall outlook for December 2017 – February 2018 shows no strong push towards a wetter-than-average summer for any part of Australia. And both daytime and overnight temperatures are likely to be above average for most of eastern and central Australia.

Why? Well the strength of La Niña events is linked to the strength of their impact on the Australian climate. And with any 2017 La Niña likely to be short lived and weak-to-moderate at best, it's not expected to push our climate into a wetter and cooler than normal pattern, like the 2010–12 strong La Niña did. On top of that, neither the eastern Indian Ocean nor waters around northern Australia are forecast to be reinforcing the impacts of the La Niña pattern—as they often do and certainly did in 2010–12. In fact, the current Indian Ocean pattern would normally be expected to keep things a little drier.

A busy year for the oceans around us

So how did we arrive here? It’s been a year of change in the tropical Pacific. At the end of last summer, in February, temperatures in the tropical Pacific were warming up and the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI), a key indicator of the strength of El Niño and La Niña events, was dropping, signalling an El Niño was on the cards. Climate models from around the globe also suggested an El Niño was possible and the Bureau's ENSO Outlook dial shifted to El Niño WATCH. But the development towards an El Niño stalled at the beginning of winter: sea surface temperatures plateaued, the SOI returned to neutral values and the El Niño WATCH was cancelled. Then at the beginning of spring, tropical Pacific Ocean temperatures above and below the surface cooled, hinting at a possible La Niña. After closely monitoring these conditions, the Bureau's experts moved to a La Niña WATCH at the start of October. Since then, strengthening oceanic and atmospheric observations, and model forecasts have elevated to La Niña ALERT thresholds. This means there is around a 70 per cent chance of a La Niña event later this year, which is around three times the average likelihood.

![]()

What happened during the last La Niña?

The last La Niña (2010–12) was one of the strongest observed so far, and corresponded with Australia's wettest 24 months on record. It started in autumn 2010 and by spring the SOI had climbed to a record October value of +18.3 (the equal-highest October SOI since 1876).

Significant flooding was widespread between September 2010 and March 2011 over large areas of Queensland, northern and western Victoria, New South Wales, northwestern Western Australia and eastern Tasmania. So it's certainly no surprise then that many Australians equate La Niña with flooding.

In contrast, this year's La Nina development started in spring (unusually late timing) and the atmospheric pattern is not as strong to date (the October 2017 SOI was only +9.1). So while we’re likely to have a La Niña summer, it may not be quite what most Australians expect.

More information

To stay up to date with ENSO check our ENSO Outlook, which is updated fortnightly with the ENSO Wrap-Up.

Currents of change: Tracking the El Niño/La Niña cycle

Subscribe to this blog to receive an email alert when new articles are published.

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.