Australia's climate in 2017: a warm year, with a wet start and finish

10 January 2018

The Bureau of Meterology’s Annual Climate Statement, released today, confirms that 2017 was Australia’s third-warmest year on record, and our maximum temperature was the second-warmest. Globally, 2017 is likely to be one of the world’s three warmest years on record, and the warmest year without an El Niño.

Read more: Explainer: El Niño and La Niña

But looking at the big picture can obscure some regional record-breaking features. Victoria experienced its driest June on record, and September saw New South Wales and the Murray–Darling Basin record their driest September since nationwide records begin in 1900. Sydney’s Observatory Hill had its driest September since records started there in 1858.

The southwest of Western Australia had its warmest maximum temperatures on record for June. Northern Australia also recorded its warmest dry season for maximum temperature.

Image: A field in Moree, New South Wales. The state had its driest September on record. Credit: Mark Wilgar

This warm year occurred despite the fact that, unlike 2016, there was no strong El Niño or La Niña pattern in the Pacific Ocean for much of the year, and the Indian Ocean Dipole remained neutral.

Read more: What is the Indian Ocean Dipole?

Wet in the northwest, dry in the east

Australia’s average total rainfall in 2017 was 504 mm, somewhat above average. But the annual average hides large swings from very dry months to damaging downpours, and large differences from the east to the west of the country.

The year began wet, particularly in the west. Tropical lows brought heavy rainfall across the Northern Territory, South Australia and Western Australia during January and February, and many places in Western Australia set new records for their wettest summer day. It was our fourth-wettest January on record nationally.

Severe tropical cyclone Debbie crossed the south Queensland coast in late March and tracked southwards delivering torrential rainfall along the east coast. Several locations received up to a metre of rainfall in two days, and major flooding occurred from Bowen, in Queensland, to Lismore, in New South Wales.

The west of Western Australia was dry for much of autumn and early winter. Winter rainfall was also low across southern Australia under the effect of a subtropical ridge stronger and further south than usual.

Heavy rain across much of Queensland and northern New South Wales during October meant that Bundaberg received more than 400 per cent of its average rainfall for October in the first three weeks of the month.

In late December, tropical cyclone Hilda became the first cyclone to make landfall in the 2017-18 Australian cyclone season, bringing heavy rains around Broome.

Image: Australia’s rainfall in 2017

A hot start

It might not have always felt like it, but 2017 was much warmer than average. It was the third-warmest year on record for Australia, 0.95 °C above average, and the warmest on record for Queensland and New South Wales. Sea surface temperatures were also much warmer than average around Australia, although not as warm as 2016.

Image: Australia’s average temperatures in 2017

New South Wales experienced its warmest summer on record, and heatwaves affected much of eastern Australia during the first two months of the year. At the same time, rain kept summer temperatures below average in the west.

The high temperatures around eastern Australia continued into autumn, over both land and sea. Coral bleaching affected the Great Barrier Reef again, the first time mass bleaching events have occurred in consecutive years.

Warm days but chilly winter nights

As winter set in, the lack of rainfall and clouds led to warm sunny days. The southwest of Western Australia had its warmest maximum temperatures on record for June.

Read more: Australia’s record-breaking winter warmth linked to climate change

However the clear skies also meant frosty mornings across much of Victoria, southern New South Wales, South Australia and Tasmania. Canberra, which is known for its chilly nights, had its lowest winter mean minimum temperature since 1982. Some locations, including Sale in Victoria, and Deniliquin and West Wyalong in New South Wales, had their coldest night on record during the first few days of July.

Meanwhile, northern Australia recorded its warmest dry season on record for maximum temperature. The mean maximum temperature for northern Australia was 2 °C above average for the five months from May to September, beating the previous record set in 2013 by almost half a degree.

A warm finish

In September, northerly air flow brought the warm air over to the east of the country, with the month culminating in a week of exceptional heat. New South Wales recorded its first ever 40 °C in September – not once, but on two separate days – and some places beat their previous hottest September day on record by more than 3 degrees.

Late-season frosts in early November caused damage to crops in western Victoria, but the cold was soon replaced by prolonged heat thanks to a slow-moving high pressure system parked over the Tasman Sea.

The northerly winds and sunny days meant that many places in Victoria and Tasmania had record runs of days warmer than 25 °C, and nights warmer than 15 °C. It was Tasmania’s warmest November on record, with temperatures more typical of late summer than late spring.

The long-lived weather system led to record-breaking November sea surface temperatures between Tasmania and New Zealand, which also had a very warm and dry November. The southeast of the country finished 2017 with our first heatwave of the summer in mid-December.

The bigger picture

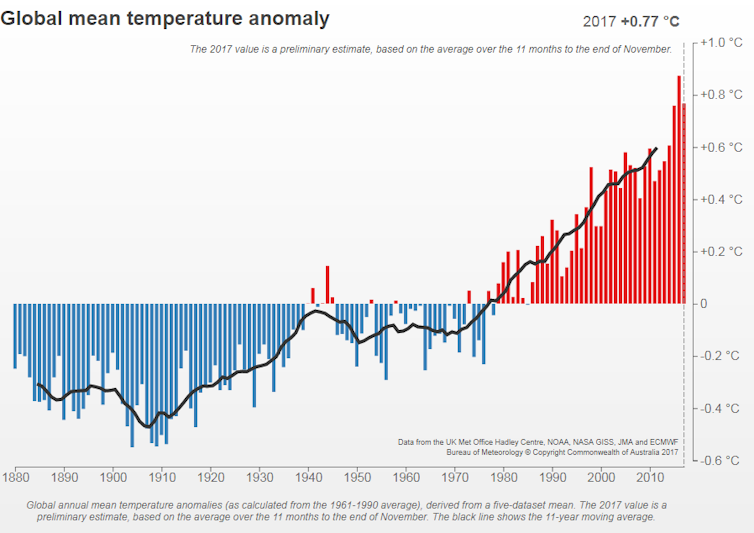

Image: Global mean temperature anomalies relative to 1961–1990, 1880–2017

The World Meteorological Organization releases the final global mean temperature for 2017 in mid-January. This enables it to collect as many observations as possible from different countries. But the January to November global average can give a pretty good idea of where 2017 will sit: one of the world’s three warmest years on record.

The planet has seen plenty of extreme weather events over the past year, including hurricanes, flooding, and devastating bushfires.

![]() Global temperatures have increased by about one degree since 1900. Mean global temperatures have been above average every year since 1985, and all of the ten warmest years have occurred between 1998 and the present. Seven of Australia’s ten warmest years have now occurred since 2005.

Global temperatures have increased by about one degree since 1900. Mean global temperatures have been above average every year since 1985, and all of the ten warmest years have occurred between 1998 and the present. Seven of Australia’s ten warmest years have now occurred since 2005.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Subscribe to this blog to receive an email alert when new articles are published.

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.