East coast lows and other lows

22 May 2019

Updated 4 July 2025

Learn about east coast lows and other low pressure systems that affect Australia's east coast.

What makes an east coast low?

An east coast low is a low pressure system that typically has these characteristics:

- is a 'closed' system – has a central lowest pressure that is surrounded by higher pressure

- forms between 20°S and 40°S (latitude) along the eastern Australian coast.

- lingers within around 200 km of the coast for at least 12 hours.

- has a pressure gradient of 4 hPa/100 km. This means that the pressure drops by at least 4 hectopascals as we move 100 km towards the centre of the low. It may also be an intense cyclonic system – one that is generating very fast winds turning in a clockwise direction.

Expected impacts are also considered when identifying the system. East coast lows are associated with high-impact severe weather, including:

- damaging to destructive winds

- heavy to intense rainfall

- dangerous seas and heavy swells that can cause coastal erosion and inundation.

East coast lows become such intense systems largely due to interactions between:

- surface of the atmosphere

- upper atmosphere

- top layers of the ocean.

These factors determine how intense the low is. They also determine where it develops and how long it lingers there. Both these have a big bearing on the impacts we see.

Video: Watch this short video explaining east coast lows.

An east coast low forms when a strong disturbance in the upper atmosphere moves near the eastern coastline. This is like a wave in the top levels of the atmosphere, around 10–15 km above the ground.

As it moves towards the coast, it causes the development of another wave in the lower levels of the atmosphere on its eastern side. This is a low pressure trough or system. As the low moves over land the temperature change causes rapid development, bringing stronger winds.

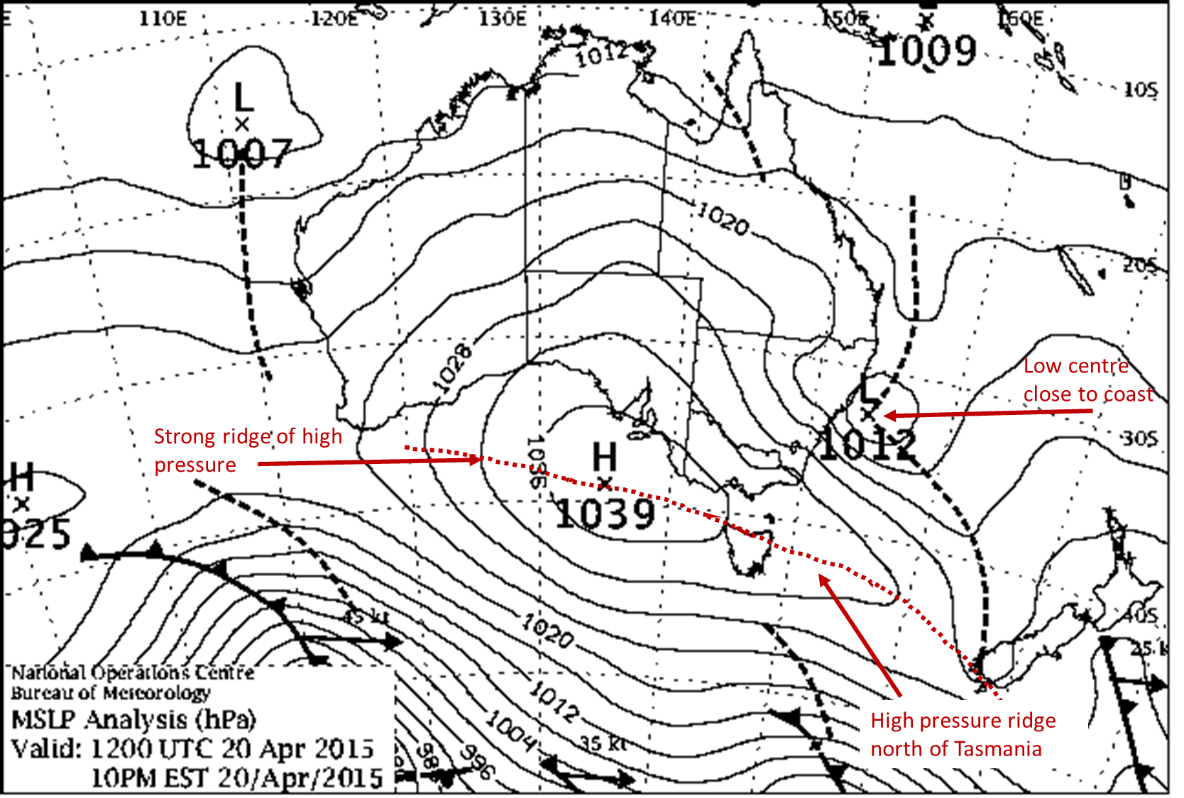

Another key ingredient for an east coast low is a cradling high. This means a high pressure system in the southern Tasman Sea, which blocks the east coast low from moving away from the coast. This makes it a much longer-lived and more significant system. The high also creates a stronger pressure gradient along the southern side of the low, causing stronger winds.

Chart: East coast low, 20 April 2015. During 20–22 April an east coast low affected highly populated areas of the central NSW coastline. Very heavy rain, gale-force winds, and damaging surf battered the coast between Nowra and Seal Rocks.

Other low pressure systems that affect the east coast

So, when is a bad-weather-bringing low not an east coast low? There are other systems over the east coast that can look like an east coast low but have very different structures and impacts. Here are 4 of the most common, along with weather maps showing how they differ from an east coast low.

Ex-tropical cyclones

Tropical cyclones usually originate north of 20°S and need tropical sea surface temperatures to develop. This gives them a unique structure and behaviour, which is very different from an east coast low.

As a cyclone drifts south, it starts to lose this structure but can still cause very dangerous weather with significant impacts. These include intense rainfall, extensive flooding and destructive winds – like an east coast low.

Sometimes an ex-tropical cyclone can transition into an east coast low.

Chart: Ex-tropical Cyclone Debbie, 30 March 2017. Northern parts of the Northern Rivers district saw rainfall totals of more than 400 mm. In the Tweed, Brunswick and Wilsons river valleys, many areas received more than 450 mm. This caused widespread flooding, and large losses to crops, property and infrastructure. Several lives were lost.

Offshore lows

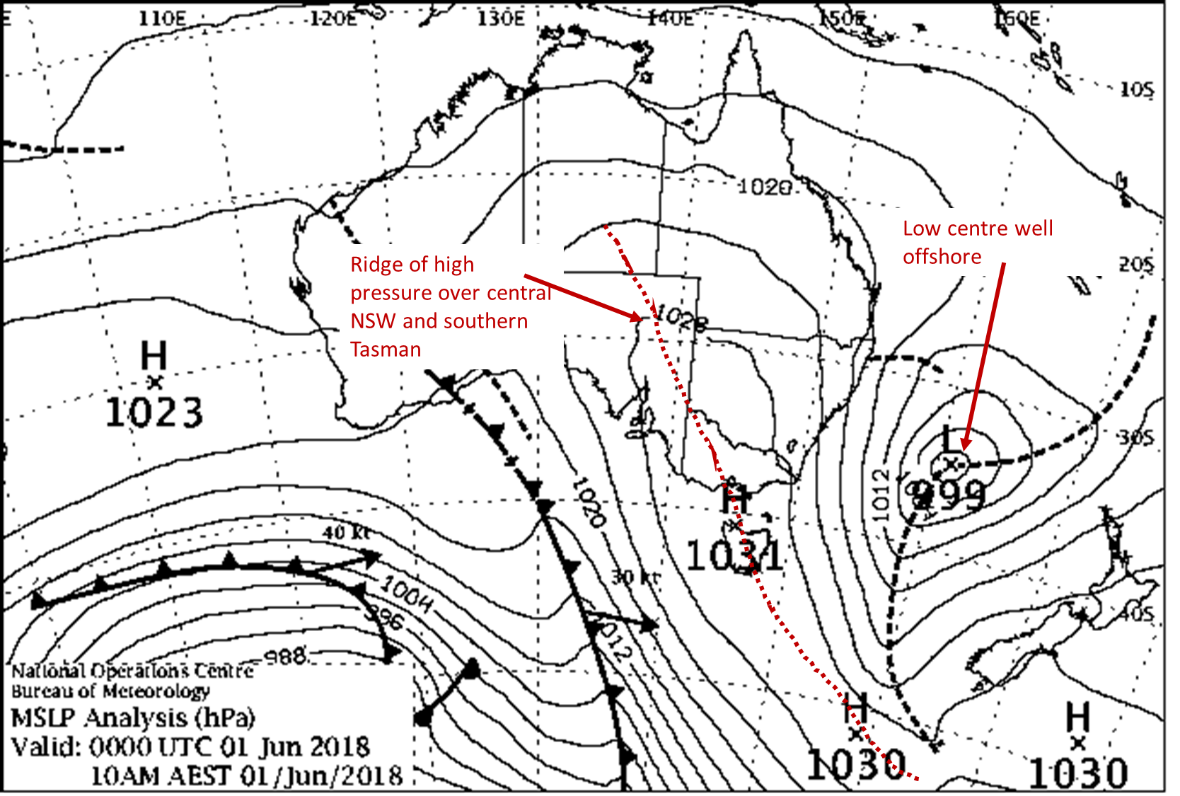

If an intense low pressure system lies further from the coast than around 200 km, we usually call it an offshore (or Tasman) low. Most often, the impacts of a low pressure system are felt closer to the centre of the low. The centres of these systems are much further away. This means they can't create the damaging winds or heavy rain along the coast that we usually see with an east coast low. Wind and rain may still occur, but they're expected to be less significant.

These lows can still cause damaging surf and be very dangerous for boating and other marine activities. They can also cause damage to property and coastal erosion. This is most likely around high tide, when the water is already closer to houses and buildings.

Chart: Tasman Low, 1 June 2018. Showers moved over coastal NSW during the early days of June, with 1–10 mm over most of the coast and up to 30–40 mm in the Hunter region. There were persistent strong southerly winds, up to gale force in exposed coastal locations. There was also large swell along the coast.

Coastal troughs

Sometimes a low pressure trough develops or moves very close to the coast – we call this a coastal trough. These troughs don't have the structure of an east coast low in that they don't have a single closed circulation. Because of this, their impact is usually less than that of an east coast low.

Small lows can develop within these troughs. These can deliver more localised, heavy rainfall and damaging winds.

Chart: Coastal trough, 4 December 2017. Moderate to heavy showers affected coastal NSW, with 40–90 mm recorded along parts of the southern coastal fringe.

Transient lows

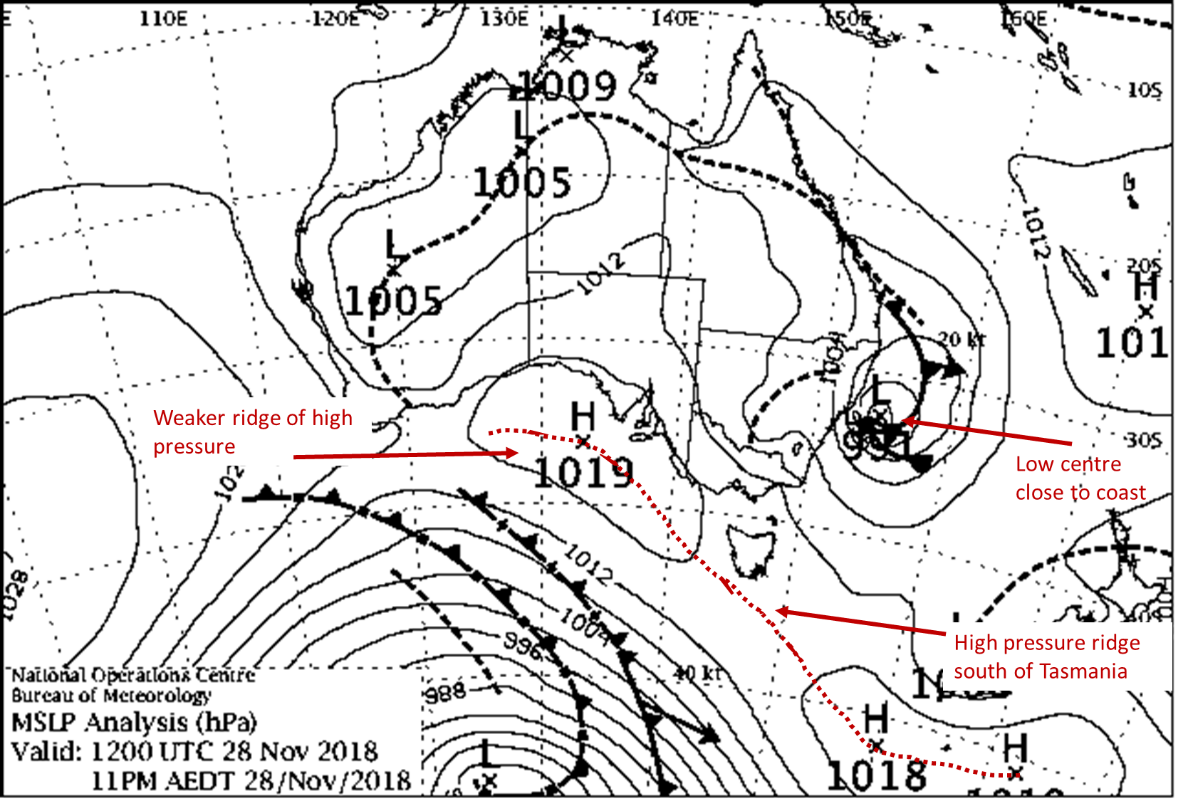

Lows can also develop very close to the coast but move away before they have time to cause widespread damage. We usually call these transient lows. They don't linger along the coast the way an east coast low would. They normally develop over land and intensify rapidly on the coast, before moving off to the east.

While transient lows can cause severe weather, it doesn't tend to be as prolonged or intense as with a more developed and slow-moving east coast low.

Chart: Transient low, 28 November 2018. During 27–28 November, a transient low delivered around 50–100 mm of rain about central parts of the coast and adjacent areas. Some locations around the Blue Mountains, Southern Highlands and Shoalhaven saw totals of 150–222 mm.

Predicting what kind of low will develop

There are often signs of a developing east coast low up to a week ahead of its impact. Whether it will cause severe weather is usually very difficult to determine until it's much closer. We look at intensification factors, such as:

- a strong upper disturbance moving towards the coast

- a strong, lingering, high pressure system in the southern Tasman Sea

- large sea surface temperature gradients near the coast.

These can give us a better understanding of how a low pressure system will develop, how long it will remain near the coast and how severe it will become.

How we warn you about severe weather

The Bureau works closely with emergency services to prepare people for the dangerous weather associated with these low pressure systems.

Over land areas and coastal areas, we use Severe Weather Warnings or Coastal Hazard Warnings to warn of:

- dangerous winds

- damaging surf

- abnormally high tides that can cause coastal erosion

- heavy rain leading to flash flooding.

If needed, we also issue Flood Warnings to warn of river flooding, and Severe Thunderstorm Warnings.

Over the sea we use the standard Marine Wind Warnings to alert people about hazardous conditions.

Always check our website for the latest warnings and listen to advice from emergency services.

More information

Top left (small) image credit: Shelf cloud over Sydney on 25 April 2015 during an ECL event, by Daniel Tran Photography.

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.