From sea to shore: a story of storm surges in Australia

02 November 2015

The barbecues remained unlit, flights were grounded, and holiday events across Darwin were abandoned as the city suffered its wildest Australia Day weather in recent memory on 26 January 2012.

The holiday washout was the result of one of the Australian coastal community's most common hazardous weather phenomenon: a low pressure system crossing over the coast, giving rise to strong, squally winds and often damaging storm surges.

Storm surges are powerful ocean movements caused by wind action and low pressure on the ocean's surface. This raises the sea level and strong winds at the coast that can create large waves, enhancing the impact. These types of events can swamp low-lying areas, sometimes for kilometres inland.

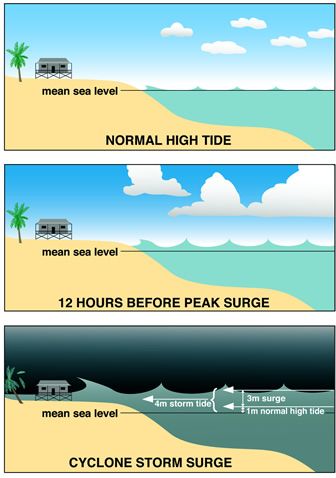

Top: normal high tide

Middle: 12 hours before peak surge

Bottom: cyclone storm surge

The highest combined storm surge and wave action ever to hit Australia was during the Mahina cyclone which struck Bathurst Bay, Australia on March 1899 and claimed over 400 lives. The ultimate high-water line was estimated at 14.6 metres (48 feet) - still claimed in some quarters as being the world record.

While significant surges usually accompany tropical cyclones, storm surges caused by large low pressure systems can also bring dangerous conditions and damage to coastal communities all around Australia - as Darwin witnessed earlier this year.

Collateral damage

While the northern capital's holiday spirits were dampened in late January 2012, damage was largely restricted to downed trees and power lines, along with washed-out events and frustrated holidaymakers. Some surfers even relished the wild weather, risking life and limb in the giant waves that pounded Darwin's northern suburbs.

But it is these very waves that could have a lasting legacy, with sections of the low-lying cliffs at Nightcliff and East Point collapsing in the heavy surf between 24 and 26 January. At the peak of the spring tides on 25 January, waves were breaking over the Nightcliff jetty and wind-blown spray blanketed the coastal road. A storm surge of 0.6 metres combined with two to three metre waves and high tides produced inundation above the highest astronomical tide level - the highest level that usually occurs in general weather conditions. The sand dunes at the popular night-market site on Mindil Beach were also severely eroded, and will require significant repairs.

A 2008 study commissioned by Darwin City Council estimated the shoreline at Nightcliff and East Point is receding at an average of 30 cm a year - with the sea moving ever closer to seafront homes. The council is investigating options for mitigating the damage, including the construction of sea walls - but with rising sea levels, regular six to seven metre tides, and frequent storm surges, erosion remains an enduring concern for Darwin residents. This is a good example of challenges faced by coastal infrastructure managers nationally - as was the case in the southeast of Australia with a storm surge event in 2011, resulting in erosion and flooding.

Coastal cliffs (Darwin) eroded resulting in walking path collapsing into the sea. Photograph by Richard Wardle.

Worst case scenarios

Storm surges are at their most dangerous when they arrive at high tide - when the sea is already at its high point, and the resulting 'storm tide' can inundate inland areas. That's what happened when hurricane Katrina made landfall in New Orleans in August 2005, resulting in the worst floods - and fatalities - in the city in over 100 years.

In Australia, by contrast, the most devastating tropical storm of the last few years - cyclone Yasi in February 2011 - made landfall in northern Queensland at low tide, significantly reducing the size and impact of its accompanying storm surge. Meteorologists say several of the most damaging Australian cyclones in recorded history, including Althea in Townsville in 1971 and Darwin's catastrophic Tracy in 1974, could have been even worse had they arrived during high tide.

Storm surges, like cyclones themselves, are hard to predict. The paths of cyclones are often erratic, making it hard to forecast where and when they will make landfall - or how high the tide will be when a storm surge strikes. Other elements contributing to the risk of storm surge include the cyclone's speed and intensity, the angle at which it crosses the coast, the shape of the sea floor, and local topography.

These multiple variants all make it very hard to accurately predict the arrival and scale of storm surges. This is why the Bureau of Meteorology uses scenario models to inform emergency managers and warn communities about potential storm surge events.

For more about storm surge, see our Tropical Cyclone Knowledge Centre.

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.