Yes, it's been raining a lot – but that doesn't mean Australia's drought has broken

25 August 2020

Heavy rain in parts of Australia in recent months has raised hopes Australia’s protracted drought is finally over. But determining whether a region has recovered from drought is a complex undertaking.

For example, a drought-stricken area may get enough rain that farmers can plant a viable crop, but that same rain may not affect major water storages. We’ve seen that in southern Queensland, where water restrictions remain in place despite recent rain.

And from a social, economic and environmental perspective, one great season of rain does not usually make up for a run of bad seasons.

So today, in World Water Week, we consider the effect of this year’s rain. The upshot is that most drought-ravaged areas still need sustained, above-average rain before streamflow and water storage levels return to average. And in other parts of Australia where little rain has fallen in 2020, unfortunately drought areas have expanded.

Three years with little rain

The Bureau isn't responsible for declaring whether a region is or isn’t in drought – that’s a state government responsibility. But we do analyse rainfall and water data, which indicate whether a region is recovering.

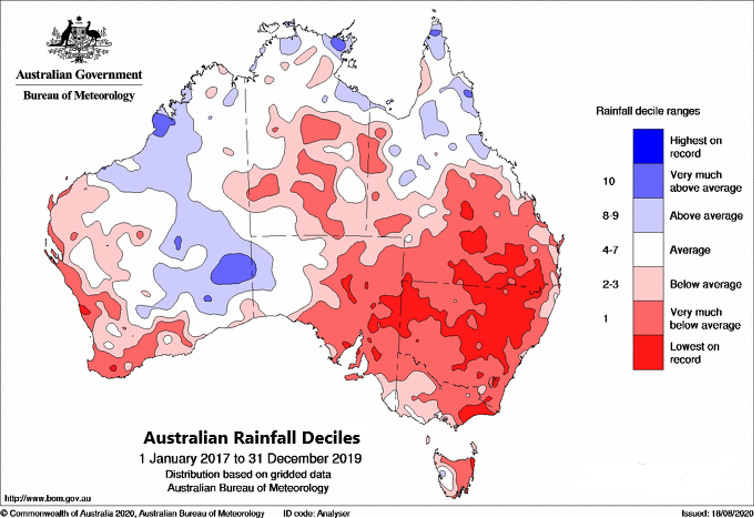

In the three years from January 2017 to the end of 2019, rainfall for much of Australia was greatly reduced – with both 2018 and 2019 especially dry. Rainfall deficiencies were most severe in the northern Murray–Darling Basin; the period was the driest and hottest on record for the basin as a whole.

These record warm temperatures exacerbated dry conditions, at times rapidly drying soils in only a matter of months. This led to periods in 2017 and 2019 that researchers have termed “flash drought”.

Map: Rainfall deciles from January 2017 to December 2019 showing the depth of longer-term rainfall deficiencies over large areas.

2020: partial recovery in the east

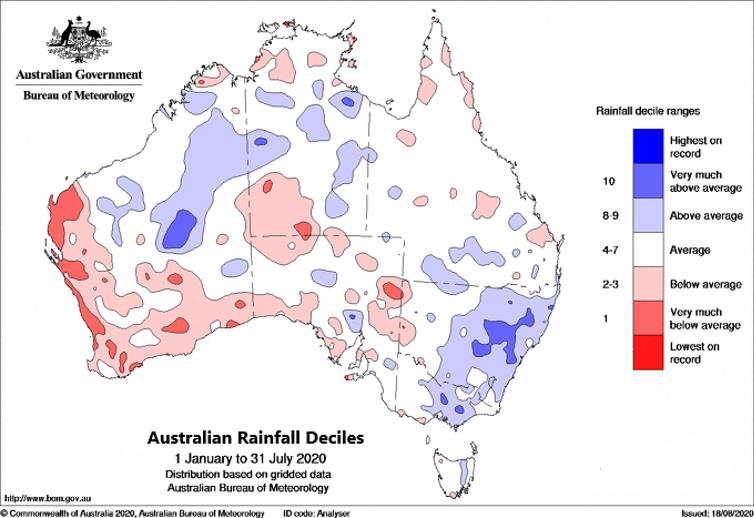

Since January this year, rainfall has been above average in some parts of eastern Australia, particularly across some of the worst drought-affected areas of central and western New South Wales and southwest Queensland. In February, much of eastern NSW experienced heavy rain, while there were more widespread and consistent falls through many parts of southeastern Australia from February to April.

But some areas have largely missed out on recent rains. Southern South Australia and southwest Western Australia have received below-average rainfall in 2020, continuing the dry conditions of 2019. Drought areas in parts of the southern coast of Western Australia and southwestern South Australia have expanded this year, and the regions may face a difficult spring and summer.

Map: Rainfall deciles from January 1, 2020 to July 31, 2020, showing the impact of recent rainfall across Australia.

Wetter soils, better crops

Eastern Australia’s recent rain has helped replenish soil moisture levels, enabling favourable crop and pasture growth in many areas. For August to date, soil moisture is above average across eastern coastal areas and mostly average to above average in Murray–Darling Basin catchments.

This increase in soil moisture is a very positive foundation – catchments are now primed to produce runoff and inflows to water storages if there is significant rainfall in spring.

But soil moisture levels are below average for August across much of southwestern Australia, southern parts of South Australia, northern Tasmania, northern parts of the Northern Territory and parts of central Queensland.

Not all dams have filled up

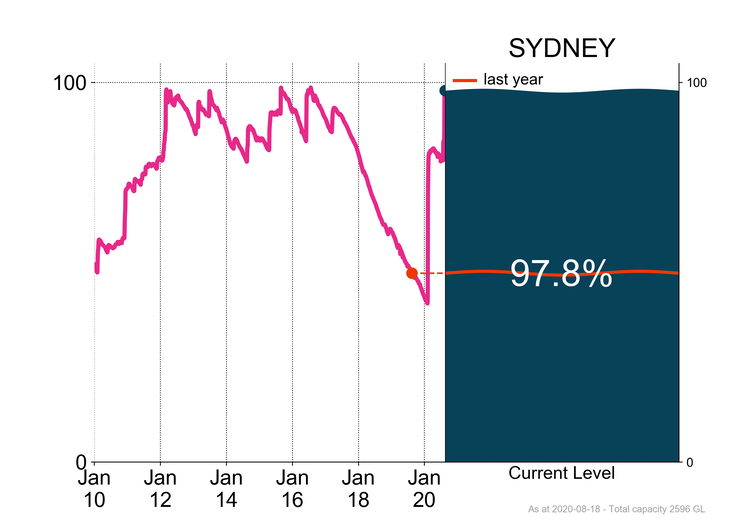

In Sydney, water storage levels had been declining since July 2016. This resulted in level 2 water restrictions introduced in December 2019 and Sydney’s desalination plant operating at full capacity. But heavy rain in February and August this year filled Warragamba Dam to capacity, further increasing Sydney’s storage levels.

Graph: Total storage as at 18 August 2020 (% of total capacity) compared to the last ten years for Sydney storages.

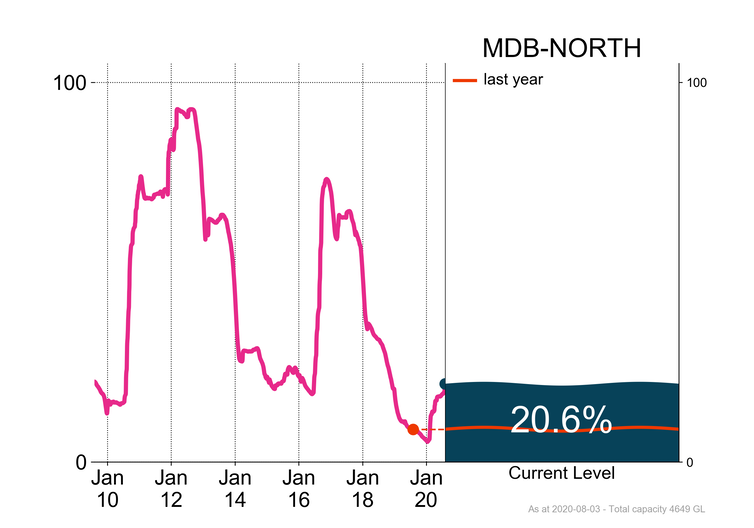

In contrast to Sydney, major storage levels in the northern Murray–Darling Basin remain low, at only 21% of total capacity despite rainfall in recent months. Unlike the significant and rapid recovery of these storages in 2010 and 2016, the current rate of recovery is slow. Significant follow-up rain is needed to replenish these northern basin water storages.

Graph: Total storage as at 31 July (% of total capacity) compared to the last ten years for the northern Murray–Darling Basin.

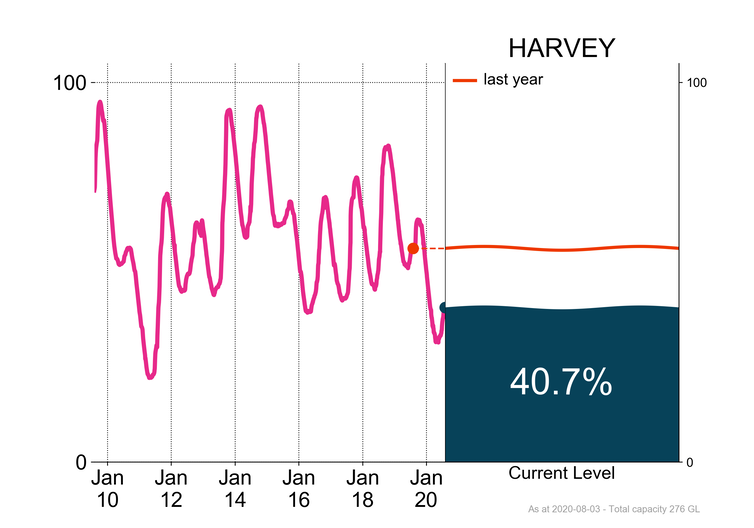

In the west, while Perth’s water supply system relies on desalinated water and groundwater to supplement its storages, the dry conditions are reflected in the Harvey rural supply system south of Perth. It needs a further 100,000 megalitres to replenish the drawdown of the past two years.

Graph: Total storage as at July 31 (% of total capacity) compared to the last ten years for the Harvey system.

So, is the drought over?

For many regions in eastern Australia, rainfall in 2020 has eased drought conditions by wetting soils and helping fill dams on farms. But most drought-affected areas still need sustained above-average rainfall for streamflow and water storages to increase to at least average levels.

Recently we raised the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) status to La Niña ALERT. This means there is three times the normal likelihood of a La Niña weather pattern in 2020. La Niña events typically result in wetter than average conditions over Australia in winter and spring.

Separately, warmer conditions in the eastern Indian Ocean may also boost the chance of a wetter end to the year.

Our latest outlook indicates the eastern two-thirds of Australia is very likely to receive above-average rainfall in coming months. However, southwest Western Australia is less likely to have above-average rainfall.

We'll provide further updates on current rainfall deficiencies through regular reports such as the monthly Drought Statement and weekly rainfall tracker.

More information

The Drought Knowledge Centre provides information about drought in your area.

Water Reporting Summaries for the Murray–Darling Basin provide an overview of water currently in storage and commitments made for this water to different users, including the environment.

The Water Storage Dashboard tracks water storages levels across Australia.

Subscribe to receive our climate and water emails.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.