La Niña and marine heatwaves off Western Australia

19 February 2021

A La Niña event is underway in the tropical Pacific Ocean. Most people know La Niña can bring wetter and cooler conditions to much of eastern and northern Australia. What's less known that it can cause severe marine heatwaves off the Western Australian coast, resulting in coral bleaching and affecting fisheries. So, what's happening off WA's coast now, what's a Ningaloo Niño and why is La Niña to blame?

Western Australia's marine heatwave

Sea surface temperatures on the West Australian coast were up to 2.5 °C warmer than average in the northwest in December and 3 °C warmer than average in the central west in January this year.

Image: Marine heatwaves in Western Australia stress marine life, such as fish and coral. Credit: James Gilmour (Australian Institute of Marine Science)

Why is this warming happening?

La Niña events are associated with strengthened easterly trade winds along the equator and cooler than average sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean. They generally bring more rain and cooler daytime temperatures across eastern and northern Australia in spring and summer.

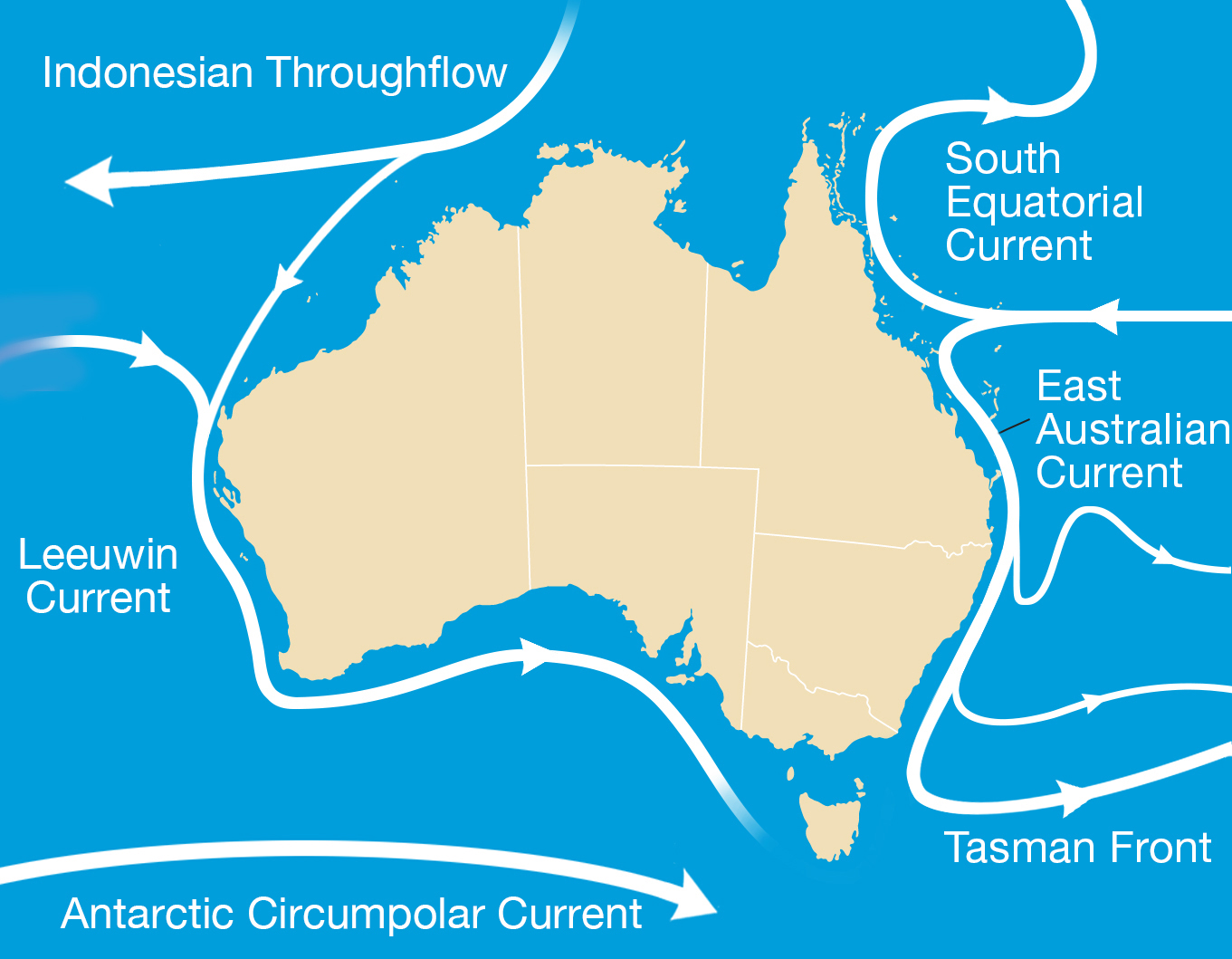

In the ocean, La Niña events typically mean more warm water is piled up in the western tropical Pacific Ocean to the north-east of Australia. These warm near-surface waters flow through the gaps in the Indonesian archipelago and down the WA coast. This strengthens the Leeuwin Current, which flows southward along the WA coast, bringing warm water south. A stronger Leeuwin Current increases the risk of a marine heatwave on the WA coast.

Map: The major ocean currents in the Australian region.

What's a Ningaloo Niño?

The last significant La Niña occurred in 2010–12 and led to a record strong summer Leeuwin Current. This led to record summer ocean temperatures (up to 5 °C above average) down the WA coast in February–March 2011. Marine heatwaves also developed during the 2011–12 and 2012–13 summers along the 1300 km coastline, because of this unusually long La Niña.

Marine heatwaves off the west coast that develop at the same time as La Niña have been dubbed the 'Ningaloo Niño'. They're 'Niño' rather than 'Niña' as they're associated with warming – like El Niño. They may involve local factors that intensify the heating, such as the collapse of the sea breezes that normally slow the Leeuwin Current in summer. This promotes warmer ocean temperatures that feed back to cause weaker winds.

These conditions led to the first significant recorded coral bleaching event on Ningaloo Reef in 2011. There was also coral bleaching at Abrolhos Islands and off the Pilbara coast. The event also affected fisheries and caused seagrass to die.

What's the outlook for this marine heatwave?

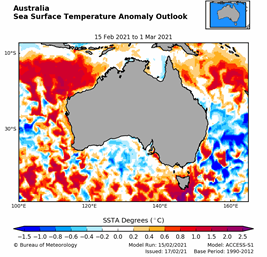

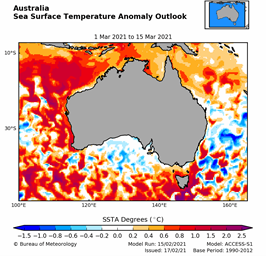

Current forecasts for the rest of February and first half of March show slightly warmer than average ocean conditions. However, the forecasts have cooled off compared to those issued at the start of February. The cooling followed a large low pressure system that passed through in early February, bringing heavy rain and winds to the WA coast. Combined with the gradual breakdown of La Niña in the Pacific, that system may have spelled the end of this marine heatwave. As such, this heatwave is unlikely to reach the severity of the 2011 Ningaloo Niño.

However, monthly forecasts for March and April still suggest considerably warmer-than-average conditions down the WA coast. Recent cool conditions may not have had much influence on the monthly forecasts yet. We'll keep a close eye on the forecasts in the next week or two to assess whether the heatwave has ended.

Image: Seasonal forecasts showing-warmer than-average (yellow and red) temperatures on the WA coast for the last two weeks of February (left) and the first two weeks of March (right).

These forecasts are used by reef and fishery managers to help plan their activities to minimise the impacts of the warm temperatures and monitor the areas affected. They're also used to help plan ocean glider missions by the Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS) to measure marine heatwaves.

Will we see more marine heatwaves in the future?

Australia's surrounding oceans have warmed since 1910, when compared to average ocean temperatures for 1961–90. Climate projections show that this warming trend is set to continue in coming decades. They also show that marine heatwaves are likely to happen more often and be more severe. For more long-term climate information, see State of the Climate 2020.

We're working with CSIRO to develop new seasonal ocean forecasting tools. These will warn of the likelihood, severity and duration of marine heatwaves. They'll build on existing seasonal outlooks for ocean temperatures.

As seen in recent years around Australia, marine heatwaves can have devastating impacts. Marine biodiversity, reefs, aquaculture and fisheries are all affected. Advance warning allows marine managers and industries to take action to minimise impacts on their stocks or marine resources.

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.