Mirrors in the sky: Demystifying the legend of the Flying Dutchman

30 June 2014

Who hath seen the Phantom Ship, Her lordly rise and lowly dip, Careering o’er the lonesome main, No port shall know her keel again... Ah, woe is in the awful sight, The sailor finds there eternal night, ’Neath the waters he shall ever sleep, And Ocean will the secret keep”

– Albert Pinkham Ryder, 1897

Ever since the 17th century, sailors have been haunted by the story of the Flying Dutchman, an airborne ghost-ship that can never put in to port and is forced to endlessly sail the world’s oceans. While the sight of a ship floating above the horizon could unsettle any seafarer, meteorologists can explain it as the result of a Fata Morgana – a dramatic ‘superior mirage’ caused by the air below the line of sight being significantly colder than that above it.

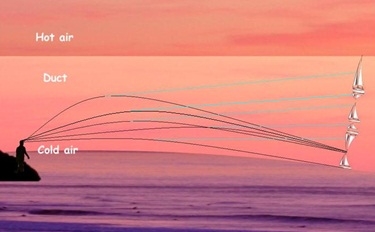

Named after King Arthur’s sorceress half-sister, Morgan Le Fay, Fata Morgana appear to be more common in the polar regions, where the surface is often characterised by shallow layers of cold air. Where this air meets a higher layer of warmer air, particularly in calm conditions, it can create an atmospheric duct that acts like a refracting lens, causing light travelling between the two masses of air to ‘bend’ – and creating some very elaborate distortions.

Our Tasmanian media manager, Mal Riley, was fortunate enough to witness a striking Fata Morgana recently off the western coast of Victoria, while he was travelling – ironically – aboard a Dutch tall ship bound for Sydney.

The reflected cargo ship with the ‘mirage layer’ clearly visible. Photo: Mal Riley

“On the horizon was a huge black square extending 1 or 2 degrees above the horizon,” recalls Mal. “Nobody could make out what it was, until the AIS (Automated Identification System) came to the rescue. It was in fact a car carrier, one of those box-like cargo ships, and our vision of it was stretched to probably three times its actual height. There was an inverted reflection of the ship on top of the real ship: two boxes, one on top of the other.”

During the afternoon, Mal and the crew of the Oosterschelde watched a procession of strange-looking ships, some stretched vertically and with mirror images in the sky, others short and squat. One of these latter vessels was their sailing partner, the elegant barque Europa, which was turned into a short, stubby ship – far less graceful than the original!

The barque Europa is made short and stubby by the bending of the light. Photos: Joep van den Brenk / Mal Riley

Fata Morgana result when two layers of air of distinctly different temperatures come together, forming a strong ‘temperature inversion’ between them. This inversion layer can act as a refracting lens, causing light travelling upwards from a distant object to be refracted back downwards towards the eyes of the observer, and causing the image of the object to appear above it – often elongated vertically or mirrored upside-down.

On the day of Mal’s voyage, winds from the northwest had carried a layer of warm air over the area. The temperature over the land was in the mid-twenties and this air moved over the water of the Bass Strait, which was 13-14°C at the time. The bottom layers of the atmosphere were thus being cooled by the cold sea temperatures.

Fata Morgana not only produce mirror images, but can magnify objects that lie beyond the horizon. Ships can therefore be below the horizon but their reflected light is distorted to such an extent that they appear to be ‘sailing’ in the sky. This is the likely explanation of the Flying Dutchman. Four hundred years ago, sailors were a superstitious lot – and it was easy for them to put two and two together and get six.

|

Diagram of the atmosphere during a Fata Morgana: Black lines represent the path of light through the atmosphere; where these lines cross, the image is inverted. Light blue lines are where you perceive the ship to be. Image courtesy of Brocken Inaglory |

Did a Fata Morgana sink the Titanic?

Historians have postulated that this kind of optical phenomenon may have contributed to the sinking of the Titanic in April 1912. There were reports of a strange haze on the horizon at all points of the compass from several ships on the day of the sinking. The weather records and eyewitness reports have led scientists to suggest that these atmospheric distortions may have been present on that fateful night.

The optical distortions could have reduced the definition of the iceberg or even ‘shrunk’ it visually. Much like the two pictures of the Europa above, the height of the iceberg could have been reduced optically, making it difficult to see. Or the lookouts could have mistaken the top of the inversion layer for the horizon, and seen nothing – as they were looking into the sky rather than at the real horizon.

But this particular mystery may never be solved.

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.