Remembering cyclone Tracy: Lessons from a ‘perfect storm’

10 December 2014

When tropical cyclone Tracy crossed Darwin in the early hours of Christmas Day 1974, thousands of people’s lives were instantly and irrevocably changed—and a new chapter was born in Australian history.

|

‘As daylight came to Darwin that Christmas morning, the people emerged to a sight that seemed to have no place with reality… The suburban streets had no children happily riding shining new bicycles; instead they were strewn with the wreckage of broken homes and shattered lives.’ – Big Blow Up North: A History of Tropical Cyclones in Australia’s Northern Territory, Kevin Murphy, 1984 |

In the meteorology trade, they teach you early on never to say 'never'. But the circumstances that led severe tropical cyclone Tracy to completely devastate northern Australia’s largest city, that left 41,000 people homeless and took 71 lives, convinced many meteorologists that it would remain the most devastating cyclone in Australia in the 20th century.

Greg Holland, a seasoned Bureau forecaster and one of the country’s leading authorities on tropical cyclones, was stationed in Darwin on that fateful night 40 years ago. In many regards, that night sealed the remainder of his career, for he would go on to become a cyclone researcher in both Australia and the United States—co-authoring the Australian Tropical Cyclone Forecasting Manual and editing the World Meteorological Organization’s Global Guide to Tropical Cyclone Forecasting.

‘The world is littered with forecasters who have said that such-and-such a weather event will never happen again,’ says Greg, ‘but we have caught up with Tracy in many respects. When you combine the significant improvements in our cyclone forecasting with the remarkable leaps in our ability to respond to emergencies, the sophistication of our communications and our much tougher building codes, I really can’t see another disaster of this scale happening again.’

Damage from cyclone Tracy

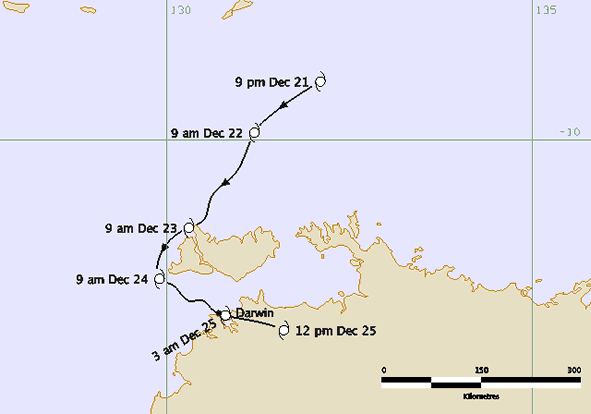

The conspiracy of circumstances that made Tracy the greatest natural disaster of its time is long and complex. For a start, Tracy was a relatively small, slow storm system that seemed to offer little threat as it meandered around the Arafura Sea for three days before rounding Bathurst Island and heading for Darwin. Three weeks earlier, another cyclone, Selma, had been predicted to impact the city but had instead turned around and headed back to sea—giving many residents a false sense of security, if not a tendency to disregard negative forecasts.

In addition, Tracy arrived early in the morning of Christmas Day, when most people were understandably distracted by the usual frenetic rounds of festive parties and family reunions. And it came in the midst of an intensive building boom, when hundreds of new houses had recently sprung up across Darwin, with little regard for building codes and none of today’s rigorous ‘cyclone roofing standards’.

But it was the conspiracy of meteorological characteristics that set the scene for the worst night of storm damage the nation had ever seen.

A direct hit

Tracy was an unusual cyclone in that it formed far north of Darwin—about 8 degrees south of the equator—where a ‘perfect’ combination of warm ocean temperatures, the development of the monsoonal wind flow and the arrival of an upper-level trough helped to intensify its power dramatically. The unified direction of the monsoonal flow and the upper-level trough—both heading eastwards and towards the pole—also helped the cyclone to curve neatly around the edge of the Tiwi Islands, without disrupting either its structure or its escalating force.

Other meteorological conditions were also ‘perfect’, with virtually no vertical wind shear—changes in wind direction between the lower and upper atmosphere, which can weaken cyclones—and an enhanced upper-level outflow, sucking clouds and moisture into the system and expelling them at high speed into the upper atmosphere.

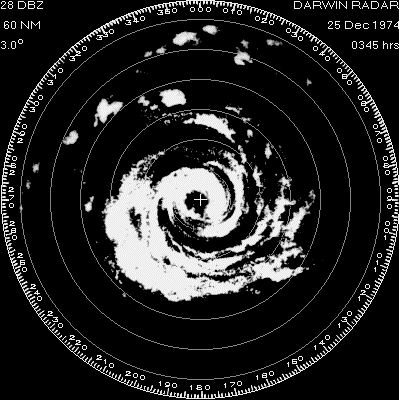

Tracy was a very small cyclone, with an eye radius of just 6 km, and the edge of its gale-force winds extending little over 40 km from its centre. Prior to tropical storm Marco in the Caribbean in 2008, it was ranked as the most compact cyclone of modern times. By the time it made landfall, Tracy was packing ferocious winds, with gusts officially estimated at up to 230 km/h—the Bureau’s anemometer at Darwin Airport reached 217 km/h before it was wrecked by flying debris.

Radar image of cyclone Tracy on 25 December 1974

Although Tracy’s maximum wind speed will never be known, what is certain is that Darwin was extremely unlucky. The eye of the storm had been oscillating back and forth as it approached the coast and, with the smallest change in its track, might have missed the city entirely. ‘If Tracy had passed 40 km either side of Darwin, there would have just been a few trees blown over,’ says veteran meteorologist Greg Bond.

In the event, however, the cyclone scored a direct hit. Its howling winds, jammed into a narrow belt, crawled through the city at less than 10 km/h—allowing time for the fearsome gusts, flying roofing materials, tree branches and other debris to exert maximum damage.

A second wind

After the eye passed over the city around 4 am, providing a brief lull, the second round of wind brought even greater devastation—completely demolishing houses that had been weakened by the first onslaught. Like many survivors, Greg Holland remembers the winds after the eye being even fiercer than those before. ‘I’ll never forget that sound,’ he says. ‘There was a continual high-pitched shriek, with a low-frequency rumble like a train superimposed on top. That was the sound of all the buildings and trees getting thrown around.’

Cyclone Tracy has often been described as ‘a manmade disaster’—a reference to the hastily-built structures and poor adherence to building codes that characterised many of the houses in Darwin at the time. Bureau veteran Mark Williams believes the building boom of the early 1970s was partly to blame. ‘The standard of construction at the time was pretty terrible, with a lot of houses erected very quickly,’ he says. ‘We had some friends living in three new houses in Stuart Park, where the builders had taken the precaution of putting in some diagonal bracing. Although they suffered some damage, all those houses were intact and repairable.’

The same could not be said for most of Darwin’s dwellings, with an estimated 60–70 per cent of the city’s houses damaged beyond repair—rising to over 90 per cent in some of the worst-hit northern suburbs.

Fair warnings

Although the devastation may suggest otherwise, the forecasts for Tracy were actually quite accurate, with comparatively fewer errors than most cyclone forecasts of the 1970s. The Darwin Tropical Cyclone Warning Centre issued its first cyclone formation alert three days before Tracy’s arrival, at 4 pm on December 21, with a full cyclone warning for the Tiwi Islands issued 24 hours later.

Track map of cyclone Tracy from 21 -25 December 1974

This was followed by warnings at approximately three-hour intervals, updating the level of risk to local communities. When Tracy rounded the Tiwi Islands, the first explicit warning for Darwin was issued at 12.30 pm on Christmas Eve: ‘Very destructive winds of 120 km/h with gusts to 150 km/h have been reported near the centre and are expected in the Darwin area tonight and tomorrow.’

Unlike most devastating cyclones—Bhola in Bangladesh, Katrina in the US, Nargis in Myanmar—where the bulk of the death and destruction was caused by storm surge, the vast majority of Tracy’s damage came directly from the wind. While the official estimate holds maximum wind gusts of about 230 km/h, reconstructions of the night have placed the winds at the Radio Australia transmission station at Charles Point, near where Tracy made landfall, as high as 300 km/h.

‘The forecasts for Tracy were actually very good for the time,’ says Greg Holland. ‘It was unusual at that time to have a tropical cyclone under watch for such a long period. We had a very good weather watch radar at Darwin, which was able to monitor it while it was tracking around the Tiwi Islands… we had that information for at least two or three days.

‘I think [cyclone] Selma was partly to blame for the slack attitude to the warnings we were putting out before Tracy. And remember it was Christmas—it was hardly surprising that people were in a relaxed frame of mind.’

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.