The 'Ekman transport' effect—cold water upwelling on Australian coastlines

15 February 2017

Have you ever gone to the beach to find the water much colder than the day before? A range of factors influence sea surface temperatures in coastal waters. This article looks at the 'Ekman transport' effect—a wind-driven process that brings colder water to the coastline.

What is Ekman transport?

Ekman transport is the movement of seawater that occurs under certain wind conditions. It is named after Swedish oceanographer Vagn Walfrid Ekman, who first described the phenomenon in 1902.

How does it work?

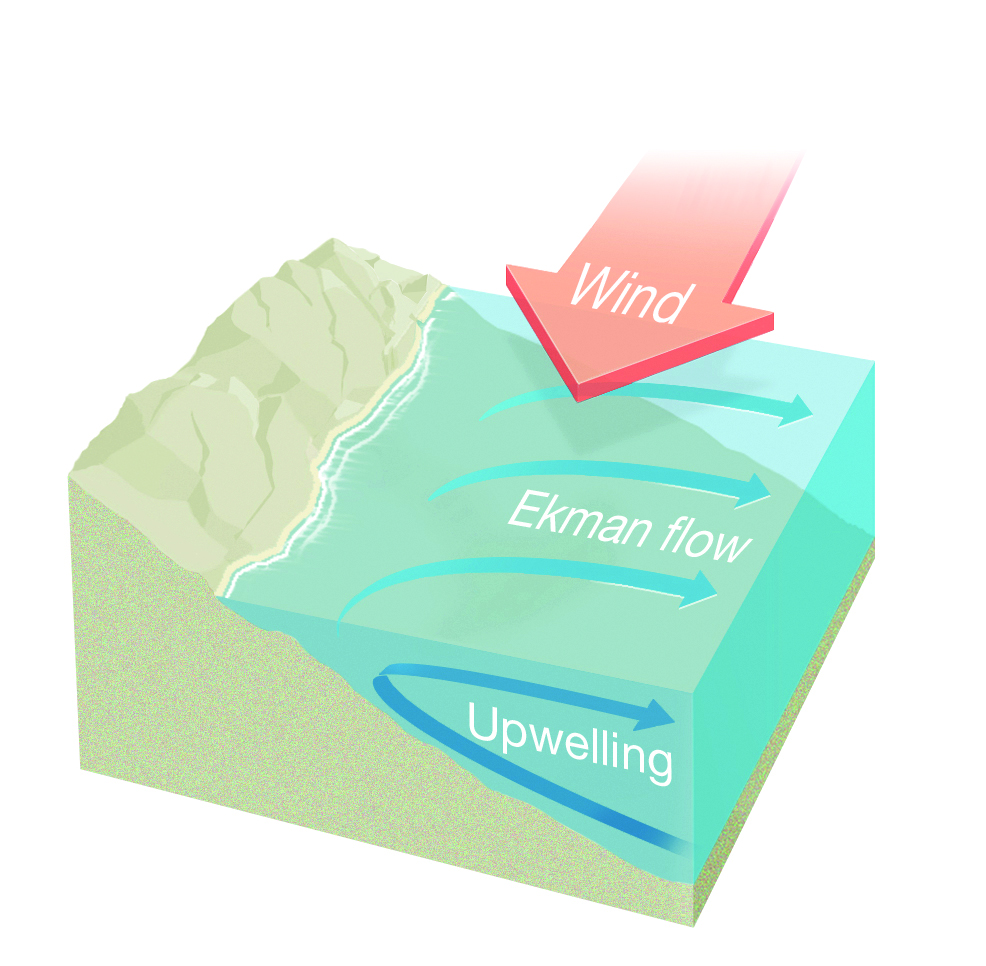

Sustained winds in a consistent direction over the ocean move the top layer (about 30 metres depth) of seawater. In the southern hemisphere, the seawater layer moves to the left of the wind direction, due to the Earth's rotation (known as the Coriolis effect).

As the top layer of water is moved by the wind, it needs to be replaced. If the coast is to the right of the wind direction, and the winds persist for more than a day, an 'upwelling' process draws up colder and more nutrient-rich water from the depths of the ocean to the surface. The longer the winds persist, and the longer the stretch of coastline that experiences a similar wind direction, the colder the water brought to the surface. This upwelled water can last for days (or longer) until wind conditions change and the seawater mixes.

The reverse process (downwelling) can also occur, bringing warmer water towards the coast from boundary currents such as the East Australian Current or Leeuwin Current.

Diagram: Winds blowing along the east coast of Australia can lead to upwelling of colder water to the surface.

Where does it occur?

Upwelling is more likely along certain parts of the Australian coastline, particularly along New South Wales, southeast Queensland and the Bonney Coast (South Australia).

An important factor is the width of the continental shelf, that is the landmass that extends with a shallow gradient from the continent underneath the ocean. Upwelling occurs when the continental shelf is narrow, i.e. where the sea becomes very deep relatively close to the shore, as the deeper water requires less time and energy to reach the coastline. This is why it's observed along the southeast Queensland and far north Queensland coasts, but typically not within the Great Barrier Reef lagoon.

Headlands and bays along the coastline may also vary the effects from beach to beach.

Your location will determine the wind direction required for the upwelling to occur. If you look out to sea from the shore, the wind needs to be consistently blowing from left to right. This means that northerly or northeasterly winds are required along most of the east coast, but southeasterly winds in the eastern Great Australian Bight.

What will you observe?

In an upwelling event, swimmers may notice that water temperatures at the beach get colder from one day to the next. In some cases this has led to hospitalisation for hypothermia.

While swimmers may find this uncomfortable or hazardous, those who enjoy fishing could have cause to celebrate. The cold water drawn up from the ocean floor is typically richer in nutrients and can boost fish numbers.

From an ecological perspective, upwelling of nutrient-rich water is important for attracting and nurturing marine life, including whales.

What other factors influence coastal sea surface temperatures?

A range of other factors influence the water temperature for swimming and other marine activities:

- Geographic location (tropical waters vs Southern Ocean)

- Time of year

- Strength and direction of ocean basin currents

- Climate patterns (such as El Niño/La Niña)

- Winds and tides

- Cloudiness

- Water depth

- River run-off, rainfall or snow melt

More information

- Keep an eye out for sustained winds forecast and observed along the coastline.

- Monitor forecasts for sea surface temperatures and currents.

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.