Clouds: your questions answered

11 May 2017

Are you curious about clouds? There’s something about them—drifting overhead day and night, constantly changing size, shape, height and colour—that captures the imagination. We hear a lot of cloud questions—here are some answers!

To get started, watch this short video to understand cloud basics—how they form, the main cloud types and what they tell you about what’s happening in the atmosphere.

Colourful clouds

Clouds can be a variety of shades from white to dark grey. The amount of cloud that sunlight has to pass through is the reason for their colour. As the light passes through the layer of water droplets, it is scattered in all directions. The thicker the layer of cloud, the more the light scatters, so the less light reaches an observer and the darker the cloud appears.

Arcs and halos

We sometimes see lovely colours in clouds that look like rainbows. Mid-level clouds contain super-cooled (between 0 and –20 °C) water droplets, while higher-level clouds comprise crystals of ice. When white light from the sun is refracted (its path bent) through these droplets or ice crystals, the light is split into its component colours (much like in a rainbow) to producing colourful arcs and halos.

Image: Circumhorizon arc over Rokewood, Victoria. Credit: Teisha Sloane-Lay

Cloud iridescence

As well as refraction (light bending as it enters and exits droplets/crystals), sunlight can also be split into different colours by diffraction—light bending around tiny objects such as water droplets less than a micron across (1/100 the width of a human hair). Diffraction scatters light waves into rings or waves of colours, randomly spread out (unlike the neat, ordered bands of colour in rainbows, halos and arcs). Iridescence is more often visible in newly formed clouds, where the droplets are mostly all the same size. It also helps if the cloud is small or thin, so most rays of sunlight that pass through it are only diffracted once (by a single droplet) each.

Video: What are iridescent clouds? Jointly produced by the ABC and the Bureau of Meteorology

Colours in thunderstorms

Clouds can appear brown before a hail storm. This is likely to be because of dust or dirt particles in the air. Clouds that produce hail are cumuliform clouds which form from the upwards movement of air. If there is dust or dirt on the ground it can get caught in the upwards motion and cause the brown tinge. The same dust or dirt provides a nucleus that water vapour in the air can condense onto and form cloud.

Thunderstorm clouds can appear green. The exact reason for this is still the subject of debate, but it seems that the green component of sunlight is scattered preferentially in stronger thunderstorms that contain large amounts of and/or larger hail—and perhaps also water droplets. It’s widely believed, and supported by anecdotal evidence, that the eerie green glow requires the presence of hail in the storm—but that doesn’t necessarily mean the storm will deliver hail on the ground. If the hail is small (less than 15 mm) and the atmosphere below the storm is quite warm, it might melt before it reaches the surface.

Image: Green-tinged storm cloud over Perth, February 2015. Credit: Ben Clark, Cloudtogroundimages

And what of that ‘red sky at night’ that so delights the shepherds and sailors, or its less delightful morning version? As the sun rises in the east, the visible spectrum of light is scattered, leaving only the longest wavelengths (red) visible. This scattering is enhanced when we have cloud to our west, which is typically where weather comes from in the mid latitudes, and can be used as an indicator of an approaching weather system (that could bring bad weather). The opposite is true for sunsets, with the scattering effect being enhanced with cloud to the east which is a sign of weather moving away.

Image: 'Red sky at night' sunset near Jondaryan, southeast Queensland. Credit: Maurits Gustavsson Photography

Do clouds affect planes?

Clouds can be pretty important for planes: Updrafts and downdrafts (columns of air moving up or down) in cumulonimbus thunderstorm clouds can cause severe turbulence; mid-level clouds can cause ‘icing’—where they freeze on contact with the aircraft and add weight and irregular shape to surfaces; and clouds close to the ground can inhibit visibility. But everyday clouds are not dangerous for planes, which is why we can fly through them.

Can bushfires cause clouds?

Yes—bushfires are a massive source of energy in the atmosphere and can cause their own clouds. One such phenomenon is pyro-cumulus. It is formed as the heat from the fire causes a rising column of air to ascend to the point that condensation occurs. In extreme cases pyro-cumulonimbus (fire thunderstorms) can occur, producing lightning that can cause more fires, and gusty winds that can make fire behaviour harder to predict. Bushfires also increase the amount of fine particles in the atmosphere which can act as condensation nuclei, forming more or thicker clouds.

Image: Pyrocumulus cloud over Pakenham, Victoria, 22 March 2016. Credit: Tadd Alexander

Are different clouds seen at different latitudes?

Yes—high clouds such as cirrus reach higher altitudes in the tropics than in temperate areas. This is down to the thermal expansion of the atmosphere and the heat at the equator forcing the molecules in the air further apart. This causes the atmosphere to extend further from Earth, creating the conditions for clouds of all types to form higher up.

There are also certain clouds that are much more prevalent at higher latitudes (towards the polar regions). The most impressive of these are nacreous and noctilucent clouds. Both are well-named: nacreous clouds are prone to displaying iridescent mother-of-pearl colouring and noctilucent clouds are brightly lit in the dead of night. Nacreous clouds sit around 20 km above the surface (in the stratosphere), while noctilucent clouds sit about 80 km above the surface (in the mesosphere). Noctilucent clouds are so high that the sun can shine on them at night, which is why they can be bright after dark.They sit up to 40 km above the surface, which gives them their unique appearance.

Bureau staff working in Antarctica have observed high clouds forming where mid-level clouds would form over Australia. They’ve also seen what is normally high cloud (ice crystals) forming on the surface and causing a beautiful phenomenon called diamond dust.

Image: Diamond dust at Casey Station, Antarctica. Credit: Justin Wood

Do clouds shield you from UV radiation?

No—so don’t be fooled into forgetting the sunscreen! The droplets of water in a cloud are very good at refracting light, which is why the light seems to be coming from everywhere at once on a cloudy day. A certain proportion of the light will bounce back into space but quite a bit will still hit the surface.

Clouds on Earth vs clouds on other planets

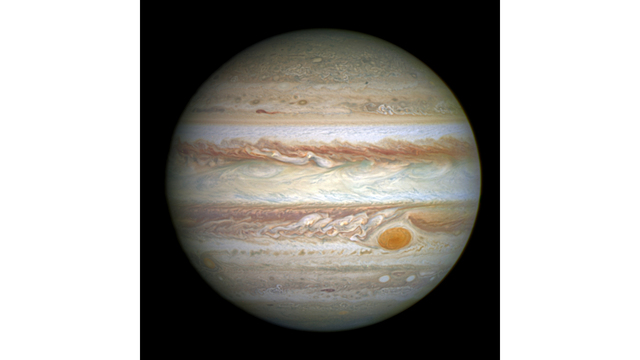

Clouds on Earth form due to the presence of water vapour cooling and condensing to what is called the saturation point and water droplets are then formed. On other planets the lack of water vapour means that clouds form as the result of the condensation of other gases. On Jupiter, for example, the clouds are liquid ammonia and methane.

Image: Jupiter, © NASA, ESA and A. Simon (Goddard Space Flight Center)

Why are there sometimes no clouds?

Clear skies are often caused by descending air or stable atmospheric conditions. The opposite—rising air—will very often cause condensation (cloud).

More information

Most of the questions answered in this article were asked by our Facebook community at a Q&A on 23 March 2017 (World Meteorological Day). You can see the original conversation here: www.facebook.com/bureauofmeteorology/videos/1402645356466027/

Blog: What’s that cloud?

World Meteorological Organization cloud atlas

Video: What is a thunderstorm?

Subscribe to this blog to receive an email alert when new articles are published.

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.