A bolt from the blue: what is lightning?

05 July 2017

Updated 20 March 2019

Snaking through stormy skies, lightning is one of nature’s most spectacular displays—but it can also be spectacularly dangerous. So what causes this high-voltage show and how can you track where it’s happening?

Image: Lightning over Perth. Credit: Andrew O’Connor, ABC News

What is lightning?

The simplest way of explaining lightning is that it is an electrical discharge that occurs within a cloud, between clouds, from clouds to the ground and even from the cloud top into the surrounding atmosphere. But this doesn’t really do justice to its force, magnitude and sheer power.

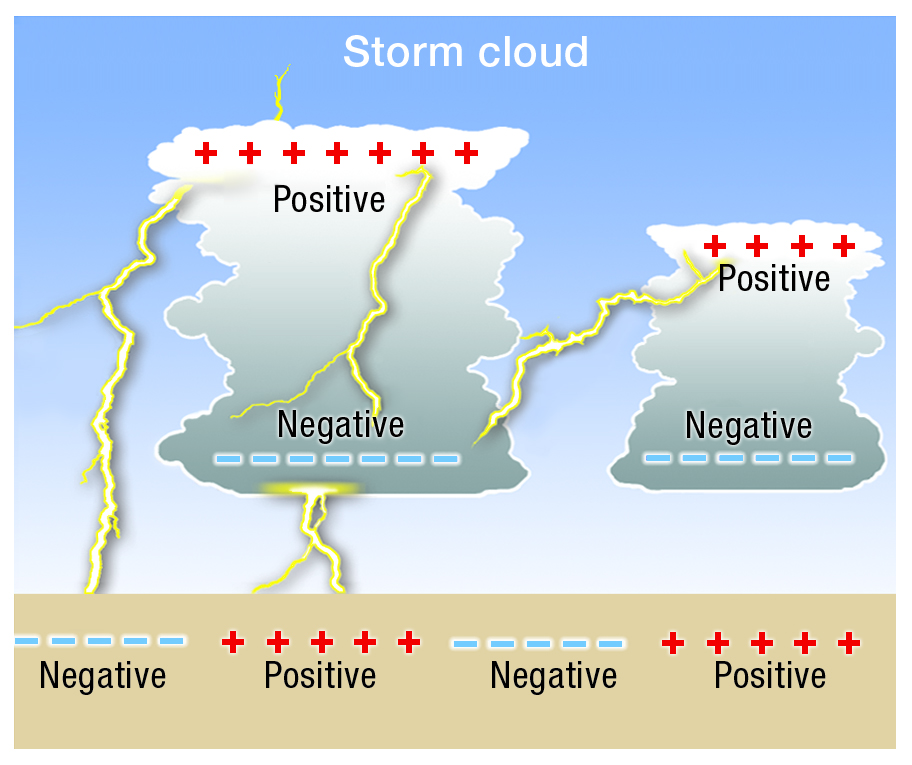

Within a developing thunder cloud (cumulonimbus), there are millions of tiny ice crystals and super-cooled water droplets rubbing up against each other as they move up and down. This causes a positive charge to develop at the top of the cloud and a negative charge at the bottom. The negative charge at the bottom of the cloud moves closer to the ground through a faint, negatively charged channel in a series of steps called ‘leaders’, while coming up from the ground are a series of positively charged channels known as ‘streamers’. When one of the negative leaders connects with the positive streamer, a powerful electrical current races from the cloud to the ground—and this is when we see the lightning bolt.

Lightning heats the air around it to a temperature of approximately 30 000 °C, which is hotter than the surface of the sun! This rapid heating makes the air expand extremely quickly in a shock wave that we hear as thunder.

Image: Lightning formation

Lightning types

Sheet vs forked lightning

People describe lightning as ‘sheet’ or ‘forked’, but the only difference between the two is where they take place. Forked lightning is the shape we see when the bolt hits the ground, and sheet lightning is lightning that occurs within a cloud, lighting it up sheet-style (so we only see the flashes, not the bolts).

Crawler lightning

When it occurs behind a cloud this is just sheet lightning, but clear of clouds you see it 'crawling' out sideways in the flattened top area of the thunderstorm (the anvil), like the branches of a tree. You're most likely to see it if the thunderstorm has a very large anvil that has hung back while the storm has moved away. It's also more likely to happen when there are clusters of thunderstorms over a large area that act as a system (meteorologists call this a meso-scale convective system).

Image: Crawler lightning. Credit: William Nguyen-Phuoc Photography

Dry lightning

This is when the thunderstorm that generates the lightning is producing little, if any, rain at ground level—the rain is mostly evaporating before it reaches the ground. You'll tend to hear about dry lightning in connection with bushfires, where it can be very dangerous. Dry lightning can start fires and the gusty winds connected with the (dry) storm can spread the flames and make existing fires harder to control—all without the relieving rain that a thunderstorm might otherwise bring.

Ball lightning

This is one of the most mysterious phenomena associated with lightning. It has been reported on numerous occasions but there is no explanation for its formation or movement. It appears to be a spherical object ranging in size from pea-sized to several metres in diameter and seems to last longer than the spilt-second lifetime of a lightning bolt.

Ionospheric lightning

Video: Mysterious electrical activity above storm clouds (jointly produced by the ABC and the Bureau of Meteorology)

Lightning is generally understood to happen within and below thunderstorms—where it can be seen, heard and felt—but relatively recent discoveries show there’s also something going on on top of storms. First identified in the late 1980s/early 1990s, ionospheric lightning is the name given to a range of electrical discharges from the top of thunderstorms. Sprites, elves and jets are all different kinds of this lightning. Gigantic jets, like the one shown below, are quite rare and occur over very short time periods—fractions of a second.

Image: Ionospheric lightning occurs from the top of thunderstorms. Credit: Jeff Miles, Snappermiles Photography

![]()

Diagram: Sprites, elves and jets all occur above thunderstorms.

Number of lightning strikes

Around the world it’s estimated that there are as many as 8 million lightning strikes per day, and around 44 strikes per second are recorded at any one time. The most lightning-prone part of the world is Lake Maracaibo in Venezuela, with nearly 300 thunderstorms per year! In Australia, Darwin is the thunderstorm capital with over 80 thunderstorm days per year.

Lightning safety

It’s estimated that there are 5–10 deaths per year from lightning strikes in Australia, and more than 100 serious injuries. If there’s lightning about, it’s important to follow thunderstorm safety advice. This includes:

- stay inside and shelter well clear of windows, doors and skylights;

- don't use a landline telephone during a thunderstorm;

- avoid touching brick or concrete, or standing barefoot on concrete or tiled floors; and

- keep checking the Bureau’s website or app and listen to your local radio station for storm warnings and updates.

Lightning forecasting and detection

There is no way meteorologists can forecast exactly when lightning will strike, or if it will be a cloud-to-ground strike or cloud-to-cloud—but we can predict thunderstorms. Every thunderstorm has lightning associated with it, so if thunderstorms are forecast there is a risk of lightning and you should consider seeking shelter.

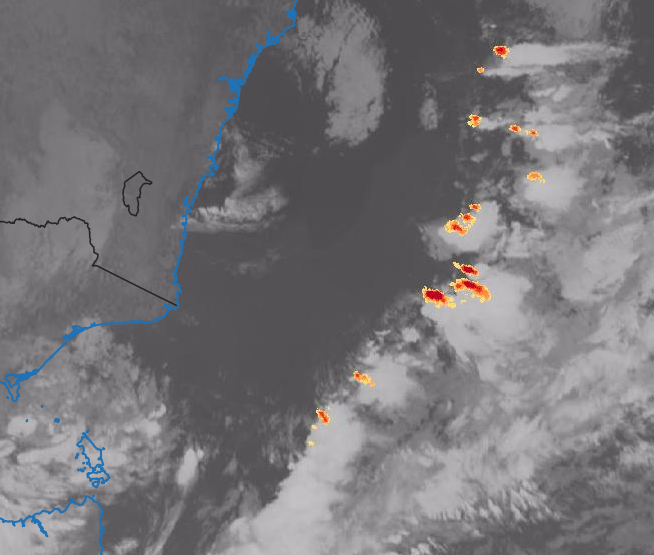

Lightning can also be detected. You can access the Bureau’s lightning detection service on our high-definition satellite viewer. In areas without access to a weather radar this information allows people to track rain-bearing thunderstorms.

In the satellite viewer, click on the bottom left menu ‘Layers’ and select ‘Lightning’ (the display shifts to infrared, rather than colour). You can zoom in or out using the ‘+’ or ‘-’ buttons at the top left of the screen and choose to display other information from the menu, such as cities and boundaries.

The viewer shows the frequency of lightning observed, ranging from two to more than 20 strikes in a ten-minute period. It also shows the most recent four hours of lightning data, in line with the satellite cloud image updates. Note that lightning information for a given ten-minute period may take a further 10–20 minutes to show on the viewer as it needs to align with the satellite image taken at the same time.

Image: Lightning off southeast Australia, 4 July 2017

More information

National warnings summary (for storm warnings)

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.