Explainer: how meteorologists forecast the weather

22 March 2018

It’s daily ‘must-have’ information around the world and for many it’s like an addiction—people tell us they won’t leave the house without checking their weather forecast! So exactly how do our meteorologists forecast the weather?

Being a meteorologist is like being a storyteller. Meteorologists take weather information—some of it highly technical—from many different sources and turn it into a digestible story that people can use to make decisions about their lives.

What information goes into a forecast?

The information and tools meteorologists draw upon to tell the story generally come from three sources: weather observations, computer weather models and meteorological knowledge and experience.

Observations

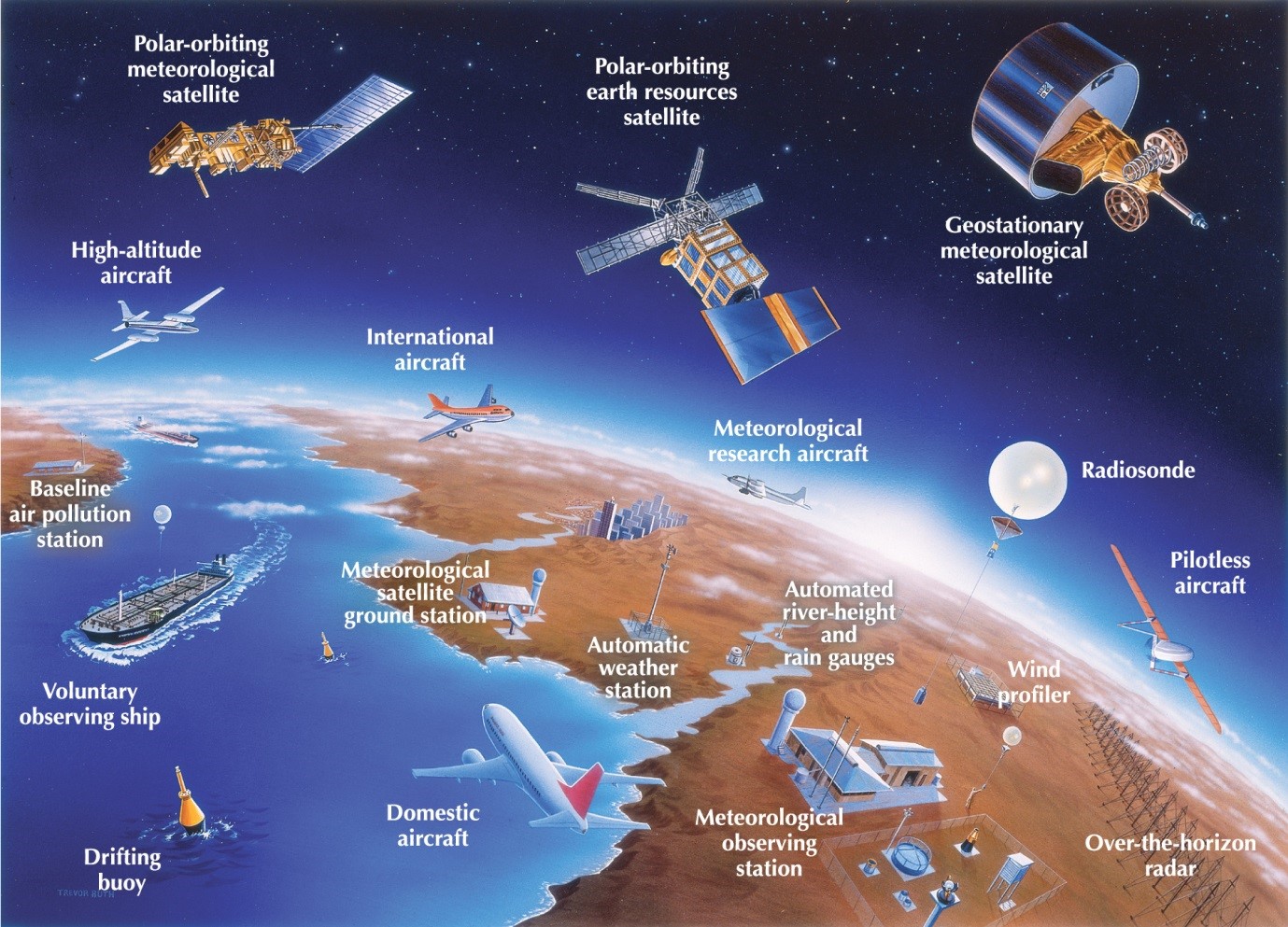

‘Observations’ are the readings of the weather that we take—not only quantities like air pressure, temperature and rainfall at the surface, but measurements in the upper atmosphere from weather balloons and aircraft, and also data from weather radars and satellites. Together, these observations of many different elements that make up the weather paint a picture of how it has been recently, and how it is right now. This information is critical—to forecast the weather into the future, we need to know where to start from!

Image: Meteorological observations are recorded by a complex array of equipment at different levels, from under the sea to far above the Earth in space.

Computer weather models

Computer weather models, or technically, ‘numerical weather prediction’ models, are the main tools we use to forecast the weather. In a nutshell, they take all of the mathematical equations that explain the physics of the atmosphere and calculate them at billions of points within the atmosphere around the Earth. The weather models require enormous computing power to complete their calculations in a reasonable amount of time, meaning they use some of the most powerful supercomputers in the world—our supercomputer, for example, can handle more than 1600 trillion calculations per second! The models take the past and current weather observations of the atmosphere and ocean as the starting point, and plug them into the mathematical equations that calculate the weather into the future.

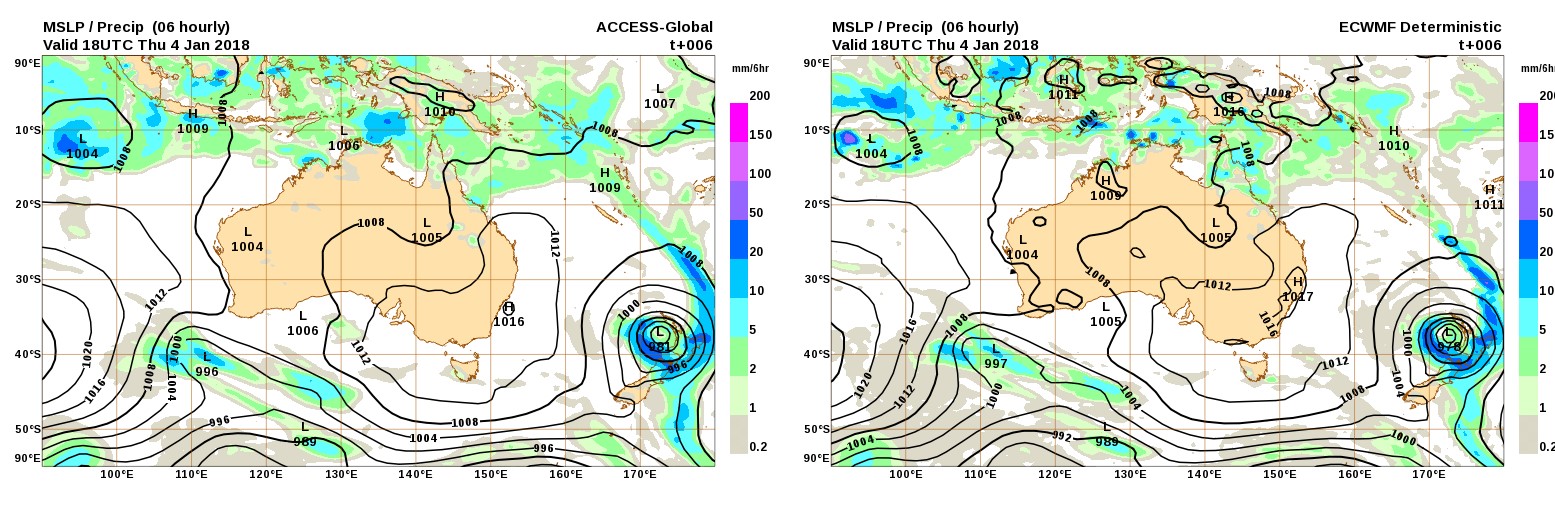

At the Bureau we have our own global numerical prediction model, the Australian Climate Community Earth Systems Simulator, or ACCESS for short. Meteorologists receive updated forecast data from ACCESS four times per day, and use specialised software to view it as maps. Additionally, they compare information from several other weather models from scientific organisations around the world to assess how consistently the forecast conditions are shown across the models.

Image: The ACCESS model (left) and the ECWMF model (right), showing forecast conditions for the same period in January 2018.

Science and experience

Data and models are a powerful force, but forecasting still benefits from the human touch. Meteorologists draw on their own knowledge of how the atmosphere works, gained through on-the-job experience and several years of university study (typically maths, physics, physical sciences and postgraduate studies in meteorology), to produce a forecast. Particular value can be added through knowledge of unique local weather features, e.g. the Fremantle Doctor in Perth and the regular afternoon 'Hector' thunderstorm over the Tiwi Islands near Darwin—or the progression of a southerly buster up the New South Wales coast. During major weather events, an experienced meteorologist's years in the job can be very useful in helping to understand the expected evolution of the weather, based on their knowledge of similar events in the past.

Image: Meteorologists overlay their knowledge and experience onto weather model information and observations to produce the forecast.

Know your forecast

The Bureau issues official seven-day weather forecasts for towns and cities across Australia. Forecasts are issued twice per day—in the early hours of the morning and again in the late afternoon. They may be updated at any time if new information comes to hand that requires a significant change to be made.

We're often asked why we only forecast out to seven days. It’s because that is about the maximum length of time that we can rely on the accuracy of computer weather models. As good as today's weather models are—and they're being improved all the time—they're not perfect. At the end of the day, weather models solve mathematical equations and algorithms that incorporate approximations and assumptions (there's much that scientists are still learning about the atmosphere) for a set number of points around the globe at set times. At this stage it’s impossible to simulate the evolution of weather around the Earth exactly for an infinite number of points at an infinite number of times.

These limitations mean that any calculations the weather model makes that aren’t spot-on at the early stages of the seven-day forecast have an increasing impact as the model calculates further into the future. Therefore shorter-term weather forecasts (say for the next two to three days) are generally more accurate than forecasts towards the end of the seven-day period.

It's also important to remember when looking up the forecast for your town or city that many features of the weather, like rain and showers, can often be on a very local scale—and differ even from suburb to suburb. So the next time you see a forecast for a 'shower or two' but you see mostly blue sky at your place, give your friend on the other side of town a call … they might be sheltering from a downpour!

More information

View forecasts for wherever you are in Australia

Right as rain: How to interpret the daily rainfall forecast

Clearing up the ‘patchy rain’: introducing a more precise forecast language

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.