Explainer: what is a marine heatwave?

07 June 2018

Marine heatwaves happen when sea temperatures are warmer than normal for an extended period. Warmer waters for swimming and surfing—what’s not to like? Unfortunately, quite a lot. The effect on marine life and the aquaculture industry can be devastating. So what causes marine heatwaves and should we expect to see more of them?

It's normal for sea surface temperatures (SSTs) to vary around their long-term average. Sometimes they're cooler than average, such as when winds blow persistently from the south (in the southern hemisphere), which can drive upwelling of cooler deep-ocean water or when there's a lot of cloud cover. And sometimes they're warmer than average, which is usually associated with decreased cloud cover, warmer winds, and reduced cold-water upwelling. But a marine heatwave is a step up from this kind of variation.

At what temperature does a heatwave kick in? Well, it's not that simple. A marine heatwave is commonly defined as temperatures being warmer than 90 per cent of the previous SST observations at the same time of year over a 30-year period, for at least five days in a row. This means that the temperature of a marine heatwave is relative to location and season. A heatwave that affects kelp forests in cooler waters is lower in temperature than a heatwave that affects coral reefs in warmer waters.

What causes them?

Like heatwaves over land, heatwaves in the ocean come about from a mix of factors.

On sunny days, sunlight passes through the atmosphere and heats the surface of the ocean. If there are weak winds this warm water doesn't mix with the cooler waters below; it sits on top and continues to heat. Such warming can be local (such as when a high-pressure system remains slow-moving for an unusual period of time), or large scale, covering much of an ocean basin, as can occur during El Niño/La Niña events.

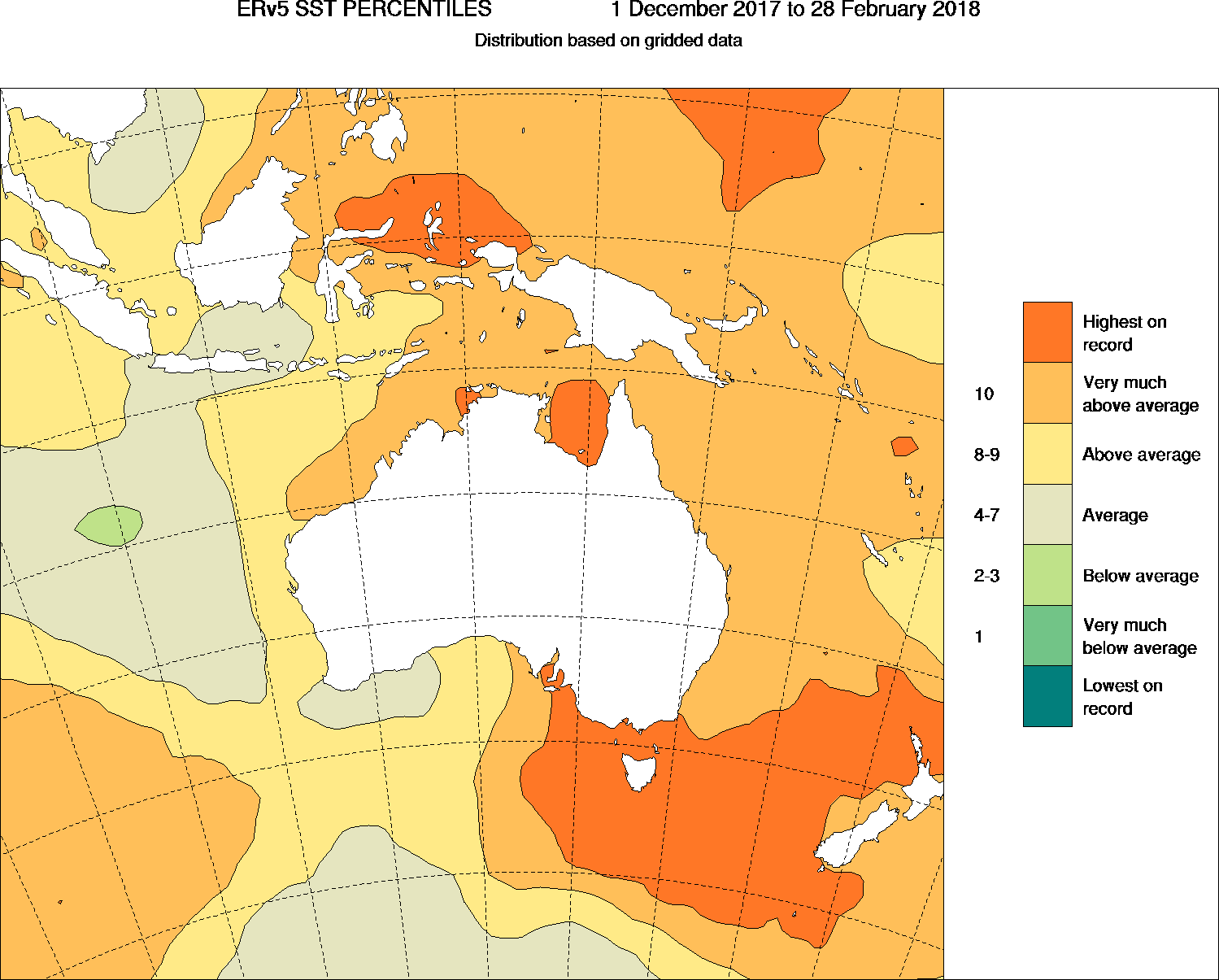

This occurred in summer 2017–18 in the Tasman Sea, between Tasmania and New Zealand. A strong and persistent high-pressure system blocked clouds and stalled winds, causing SSTs to surpass average conditions by more than 4 °C for several months. This event was so significant that the Bureau and New Zealand's National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research released a joint Special Climate Statement about it.

Image: Summer 2017–18 sea surface temperatures were some of the warmest ever recorded in the Tasman Sea.

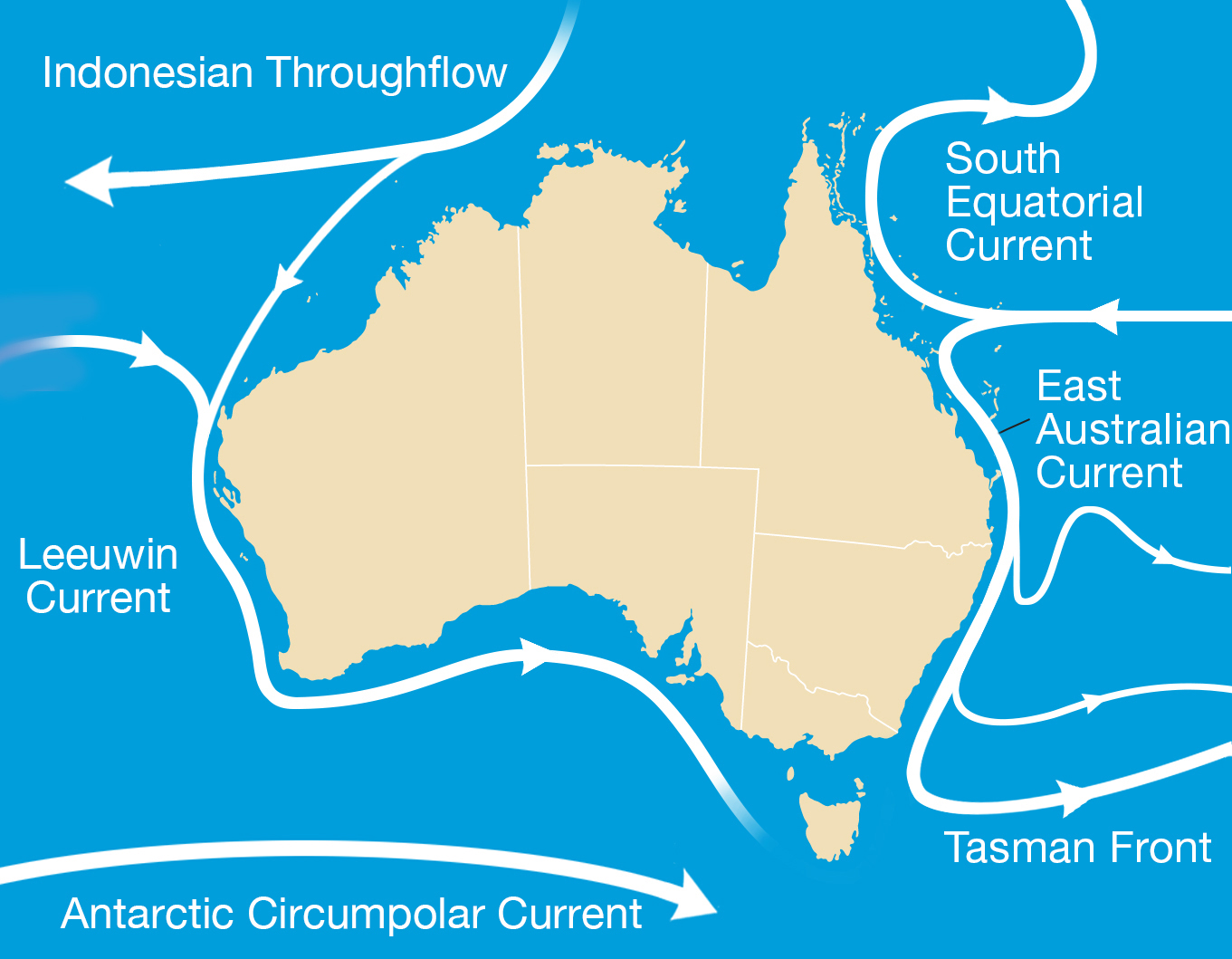

Another contributor to marine heatwaves is warm water moving from one location to another (cooler) location. Ocean currents vary over time and can wiggle around, speed up and slow down, and replace colder water with warmer water. An example is when warm waters from the Western Pacific Warm Pool pass through the Indonesian Throughflow, and down the coast of northern Western Australia via the Leeuwin Current.

We saw this during the strong 2010–11 La Niña, which led to bleaching on Ningaloo Reef in Western Australia. Another significant event occurred in 2014 when the East Australian Current moved warm waters down to Tasmania, changing the fishing conditions and local weather.

Image: Ocean currents can move warmer water into cooler locations, causing marine heatwaves.

What are the impacts?

Warmer waters can bring both good and poor fortunes. While they can create warm surfing conditions and bring new species for fishing, they can also have negative effects, such as:

- slowing the growth of salmon;

- activating deadly viruses in infected oysters;

- stressing immobile creatures like shellfish, oysters and abalone;

- disrupting the natural cycles of temperate seaweeds which then alters habitats;

- collapsing seagrass regions causing the release of carbon dioxide; and

- bleaching corals.

What’s the outlook for the future?

Oceans are incredibly important to our climate as they are the largest ‘sink’ of heat, absorbing up to 90 per cent of the additional energy arising from the enhanced greenhouse effect. Attribution studies have shown that as the oceans take in this heat, the frequency and intensity of marine heatwaves increases. So we are likely to see these events occur more frequently, changing the seascape and causing species to move to different areas.

Sea temperature monitoring and prediction

The Bureau monitors sea surface and subsurface temperatures through a variety of observation platforms, including deep-ocean buoys and floats, and satellites.

There is special interest in the Great Barrier Reef. Reeftemp shows SST around the reef and provides data on when it is experiencing high temperatures for an extended period. We also provide predictions of when the reef should or shouldn't expect marine heatwaves in the upcoming months. This information can be accessed and used by government agencies, reef managers, policy-makers, researchers, industry and communities to help better understand and manage the reef.

More information

Ocean forecasts and model data

Forecast sea temperatures and currents

Subscribe to this blog to receive an email alert when new articles are published.

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.