Cold fronts: your questions answered

25 July 2018

They roll across the country from west to east, causing temperatures to plummet and often bringing rain, storms and strong wind. So why do they happen, how do we know how severe they'll be and how do Australia's compare to cold fronts elsewhere in the world? You asked the questions—here are the answers!

To get started, watch this short video to understand cold-front basics—what they are, what happens as they pass through and why they bring the weather they do.

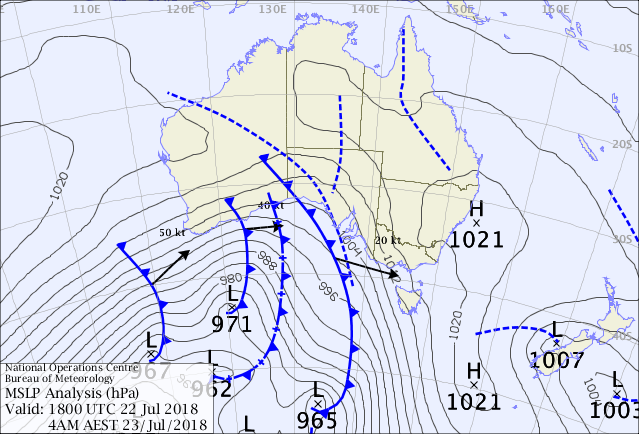

A cold front is the boundary between a relatively cold air mass and a region of warmer air. In the Australian region, warm northerly winds occur ahead of the cold front, while colder southerly winds typically follow behind it. On a weather map you can recognise a cold front as a blue line with small triangles poking out the front.

Image: Weather map showing cold fronts advancing from west to east.

Why do cold fronts form?

To understand why cold fronts form it helps to know something important about how the atmosphere works—it is constantly trying to maintain temperature equilibrium. Heating from the sun causes an excess of warmth at the equator but a deficit at the poles, so the Earth needs to find a way to balance that all out. A cold front is one of the mechanisms that does this.

You can think about the atmosphere as being like when you jump in a hot bath and it's too hot, so you run some cold water and swirl it around. At first there are 'cold fronts' and 'warm fronts' within the bath, then you mix it around so it's an even temperature. This is essentially what the atmosphere is doing within weather systems right across the planet—trying to even up the temperature imbalance.

Why do cold fronts bring bad weather?

Cold fronts slope upwards with height, so as they 'wedge' in under the warmer air, they lift it up. If that warmer air is moist, the water vapour condenses and cloud will form. This process is essentially why rain often accompanies a cold front.

Some of the most hazardous weather is associated with cold fronts and we often issue Severe Weather Warnings. This is generally because of wind (if we expect wind gusts greater than 90 km/h) or if heavy rain is likely.

While many cold fronts bring short, sharp bursts of heavy rain, they don't often bring the prolonged rain that might lead to floods. This is because they tend to move through quite quickly. However if a succession of fronts moves through within a few days, then flooding can sometimes be a concern with high rainfall accumulations.

We usually think about cold fronts in winter and certainly they're the ones that bring snow to the alpine regions, rain across southern Australia and strong winds. However, cold fronts can be significant in summer as well. For example, Black Saturday in February 2009 saw devastating bushfires and loss of life across southeastern Australia. In that case, a cold front saw strong, gusty northwesterly winds followed by a sharp westerly change.

Images: A cold front rolls through Moorabbin airport on 17 July 2018. Credit: Rob Embury

How do you determine the severity of a cold front?

We use several tools to 'diagnose' the strength of a cold front. We can view the state of the cloud on satellite imagery—thicker cloud generally means more uplift, heavy rain and, possibly, storms. We also use a range of different computer weather models sourced from agencies around the world as well as Australia's own Australian Climate Community Earth Systems Simulator (ACCESS) model. It's the job of a forecaster to then analyse information provided by these models, looking at trends and identifying the different attributes of a cold front—or any weather system for that matter.

How far in advance can you forecast a cold front?

The computer weather models that we use go out to around 7–10 days, however we take any information this far out with a grain of salt. We can be fairly confident of a cold front affecting an area maybe a week out, but as we get closer and closer to the event, that's when we can say with greater certainty what we can expect and where.

Why do most cold fronts come from the west?

The Coriolis force, due to the rotation of the Earth, is the reason we see cold fronts move from west to east in the mid-latitudes, including across southern Australia. Southwest Western Australia is normally the first place to get strong cold fronts right off the Indian Ocean. Typically, we'll see that cold front move through to the southeast a day or two later. If the Earth didn't rotate, we wouldn't experience swirling weather systems like low and high pressure systems and the cold and warm fronts that define the boundaries between them.

Are cold fronts forming further south because of climate change?

The extent to which cold fronts push north over Australia depends on a range of factors. The main one is the position of the subtropical ridge (a large belt of high pressure that sits over the centre of Australia)—the further south this ridge, the further south the cold fronts. We saw this in winter 2017 when southern Australia recorded a very dry season (June 2017 was the second-driest on record). Research shows that global warming is affecting rainfall over southern Australia, in part due to the strengthening of the subtropical ridge which leads to more 'summer-like' weather.

However, it's important to remember that climate happens over a long period of time (tens, hundreds and thousands of years), while weather is what happens on a day-to-day basis, and so we can't say that one weather event is evidence for or against climate change. We have to look at long-term trends before we can say that climate change is causing cold fronts to become more intense or to occur further south. This is a body of work that is still growing as we gather more data. We know that the atmosphere is warming, but we're still learning about how that affects the weather.

How do Australia's cold fronts compare to those in Europe or North America?

The cold fronts in Europe and North America bring more snow and cold weather than ours. This is because these regions have large land masses between them and the North Pole, whereas in Australia we only have the Southern Ocean between us and Antarctica. Land masses heat and cool much more efficiently than ocean waters. This means that the cold air following a cold front is extremely cold in the northern hemisphere in winter. Also, Europe and North America are closer to the North Pole than we are to the South Pole.

How does cold air move over water vs over land?

Air tends to move more slowly over land than water due to friction as it encounters mountains and other topography. Friction causes the air to bump, bend and bounce around, whereas oceans are much smoother to pass over.

Interaction with the land can shorten the life of a cold front. For example, southwest Western Australia is often affected by strong cold fronts along the west coast, but as the front moves east and over land, it can be cut off from a moisture source such as the ocean, and then weaken.

However, there are multiple factors that affect cold front movement and duration. As well as interaction with land, these include atmospheric influences such as weather systems like blocking highs that may cause colder air to move slowly or slip away, or the speed of the upper jet stream.

Are cool season tornadoes caused by cold fronts?

Overall yes, cool season tornadoes, or 'coldies', tend to be produced by cold fronts or the showery, unstable air masses behind them. Southwest Western Australia is one of the more tornado-prone regions in the world (but still well behind Tornado Alley in the US), especially with cold fronts during winter.

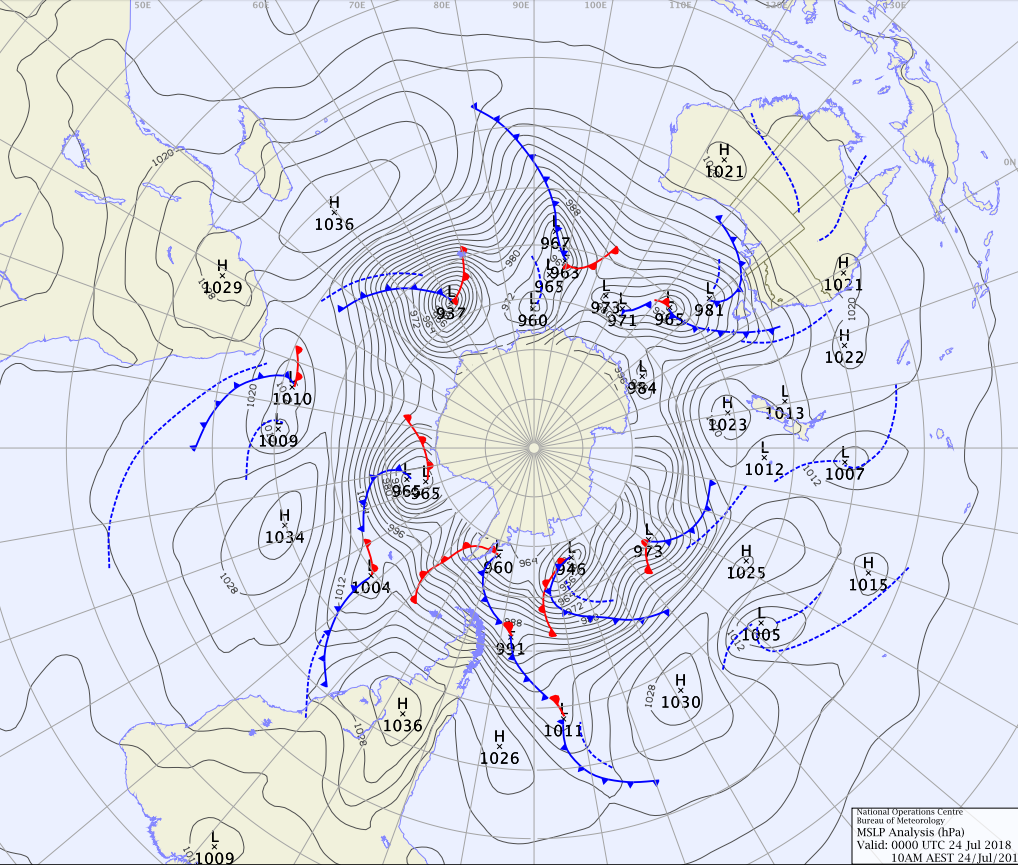

Is there such a thing as a warm front?

Yes. On the weather map these are shown as a red line with small semi-circles protruding out front. A warm front is the opposite to a cold front in that it's warm air pushing out the cold. We don't often see them in Australia as they tend to occur south of us. However, they are common across Europe, North America and Asia. Just like with a cold front, the temperature change can be quite large once a warm front moves through, but it happens more gradually than a cold front. For example, it could go from 10 °C to 20 °C over a number of hours.

Image: This weather map of the southern hemisphere, centred on Antarctica, shows warm fronts (in red) as well as cold fronts.

More information

Most of the questions answered in this article were asked by our Facebook community at a live Q&A on 9 July 2018. You can see the original conversation here: https://www.facebook.com/bureauofmeteorology/videos/1907669942630230/

Blog: The big chill: what is a cold front?

View current weather maps

Subscribe to this blog to receive an email alert when new articles are published.

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.