The wet and the dry: seasons in the tropics

24 December 2018

In Australia’s tropics, the familiar seasons of spring, summer, autumn and winter don’t apply. Instead, it’s all about the wet and the dry. So why are there only two seasons and what’s behind the weather we experience in each of them?

Why do the tropics only have two seasons?

Weather is driven by the sun and the uneven distribution of heat between the equator and the poles. In essence, weather is the atmosphere reorganising itself to try and smooth out this temperature difference. The Earth's axis also has a tilt relative to the sun, meaning a location will receive a different amount of heat at different times of the year: some parts of the year will be warm (summer) and others will be cool (winter). This gives rise to the four seasons we are familiar with.

However, since tropical regions are close to the equator, the difference in the heat they receive over the course of the year is only small, leading to small variations in temperature. A more noticeable change between these two times of the year is the amount of rain that falls, with a distinct wet and dry season. So it's more appropriate to describe the season in the tropics by rainfall amount than the temperature.

Image: The northern dry season is the envy of Australia's southern regions. Credit: Nicholas Loveday

Paradise: the dry season

The dry season in northern Australia, what a time of the year! With abundant sunshine, an average maximum temperature in the low 30s and minimum temperatures reflecting the maximums in southern Australia, it sounds like paradise to windblown, shivering, drenched southerners.

As the name suggests, the dry season is characterised by dry weather (or drier than the wet season). It occurs between May and September in the southern hemisphere. During this time of the year, the sun is located over the northern hemisphere, so the southern hemisphere receives less heat and starts to cool down. This means that the high pressure systems that circle the Earth move to lower latitudes. In the Australian winter season high pressure systems migrate from the eastern Indian Ocean through the Great Australian Bight into southeastern Australia.

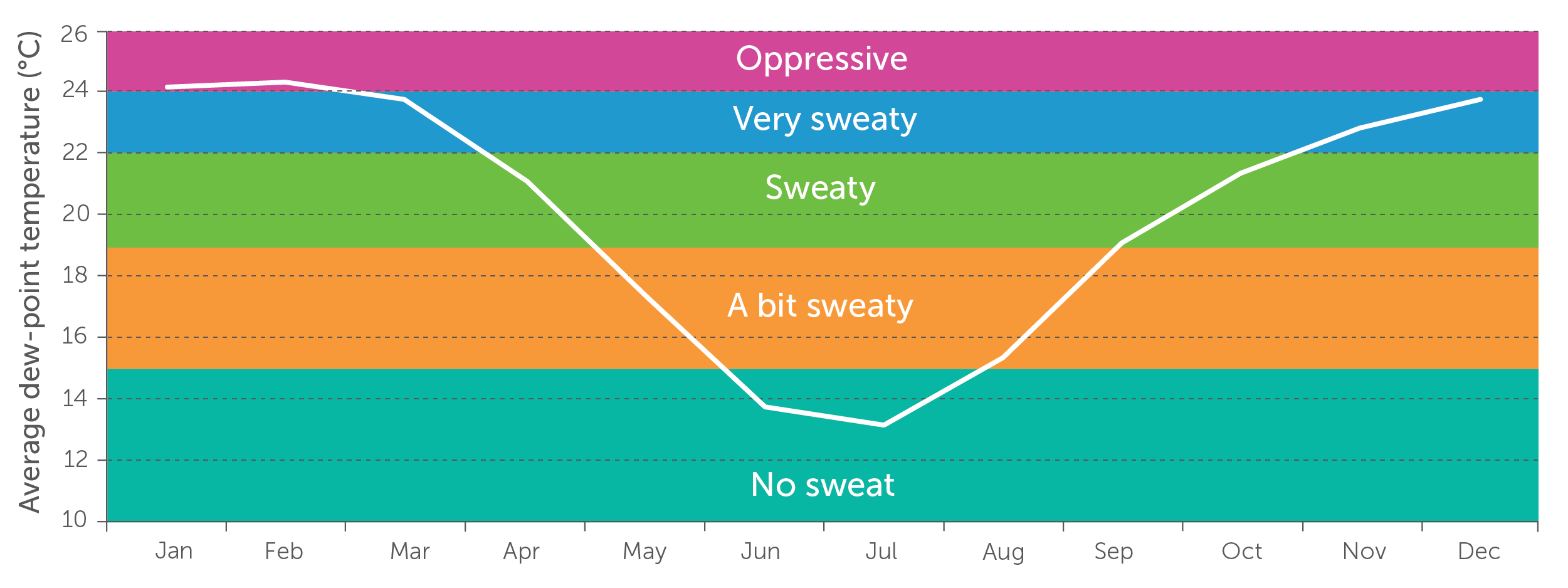

Cold air doesn’t hold as much water vapour as warm air. The amount of water vapour defines the dew-point temperature—the temperature at which water vapour in the air would condense into liquid if the air was cooled. A high dew-point temperature means there is lots of water vapour in the air and it’s likely to feel humid. Cold air can’t hold much water vapour so the dew-point temperature is generally quite low.

Image: Darwin's average dew-point temperature (and sweaty feeling!) is lowest in the dry season.

So we have cold, dry air and high pressure systems sitting south of the tropics. How do these combine to give us our dry season? When a high moves into the Great Australian Bight and southeastern Australia, the trajectory of the winds around the system drag relatively cool, dry, mid-latitude air north into the tropics, resulting in the cool, dry weather. Though there is one thing missing. If the high is dragging southern weather north, why isn’t it freezing cold and raining in the tropics too? The answer is Australia is a big country. There is 3000 km between Adelaide and Darwin, so the air will take several days to make the journey. This whole time it is being warmed by the arid desert in central Australia. There are no water sources across central Australia where the air moving north can pick up moisture. Therefore, when the air arrives in tropical Australia, it is warm and dry…very much like paradise.

A natural sauna: the wet season

The wet season in northern Australia—also a great time of the year! The grass is lush and green, and the waterfalls are pumping. However, the wet season isn't for the faint-hearted—there are six months where the temperature rarely drops below 21 °C (or even worse, 24 °C near the coast) and the humidity is constantly above 60 per cent.

The wet season is characterised by wet weather (no surprise there) and occurs between October and April in the southern hemisphere. The wet weather results from the hot and humid conditions that develop across the north of Australia. With the relentless sun beating down on the moisture-starved land after months without rain during the dry season, heat is transferred to the atmosphere above, causing it to expand. When the atmosphere at the surface expands, it can only rise, resulting in lower pressure and causing what is called a ‘heat low’. A heat low typically develops over the Kimberley region of Western Australia around October with a trough extending across the base of the Top End into inland Queensland and along the Pilbara.

Image: This chart shows a heat low, with the trough across the Top End shown by the dotted blue line.

The development of the heat low and trough is the first sign of the pending wet season. Once these features develop, northern Australia is cut off from the mid latitudes as the cool southeasterly winds to the south struggle to push through, leaving the tropics to swelter under the approaching sun. To make things worse, winds travel clockwise around low pressure so a prevailing westerly wind develops north of the heat trough, meaning for most of the tropics the wind blows onshore from the warm ocean. This warm maritime air is full of moisture so not only does the temperature rise north of the heat trough, the humidity does as well. Another factor that increases the humidity is the stronger sea breeze that occurs during the build-up—the first few months of the wet season between October and December, where temperature and humidity rise and rainfall is very isolated. The wet season is 'building' during this time. With high humidity, an unstable atmosphere and a heat low/trough, conditions are prime for showers and thunderstorms—a common feature of the wet season.

Image: Wet-season thunderstorm, Legune Station, Northern Territory. Credit: Elise Lawry

The monsoon

As the sun moves further south towards the Tropic of Capricorn, the area of low pressure over northern Australia grows. At the same time, the northern hemisphere winter is starting, so pressure rises, in particular over Siberia in Russia. Since the air flows from high pressure to low pressure, there is a transport from the Siberian high, through Southeast Asia, across the equator and towards the low pressure heat trough over northern Australia. In a similar fashion to the southeasterly winds of the dry season, the winds warm as they head towards the equator and pick up moisture from the tropical oceans. We call this warm, moist air the monsoon and it typically arrives in late December.

Over the months of December–April, the monsoon varies across northern Australia due to a complex mix of factors such as tropical waves in the atmosphere (Madden–Julian Oscillation or MJO, equatorial Rossby waves and Kelvin waves), the subtropical ridge (both northern and southern hemisphere) and the upper weather pattern (conditions above the surface). At times the monsoon flow can be strong, resulting in severe monsoon squall lines, tropical cyclones and lots of rain. At other times it can be weak with sunny skies and very little rainfall. If conditions are right, the prevailing westerly wind of the wet season might even turn around and become an easterly as the heat trough weakens or is pushed offshore. This is called a monsoon break and often feels like the build-up.

More information

Australia’s Indigenous peoples recognise different seasons across the Top End. Visit Indigenous Weather Knowledge to find out more.

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.