When the temperature isn’t the actual temperature

22 August 2014

The Bureau has begun to include the ‘Feels like’ temperature in several of its forecasts. So how precisely should we be using this ‘new’ weather measurement?

We all know what the air temperature means, don’t we? It’s the warmth or coldness of the outdoor air, measured in degrees Celsius, and a figure we all use to work out what activities we can do and what we should wear from day to day. It’s as simple as that.

Or is it?

In the 100-plus years that the Bureau has been issuing weather forecasts, the daily minimum and maximum temperatures have always been central to the process. Together with rainfall, they’re one of the most widely used datasets among our multitude of weather and climate information. They’re the key statistics we need to stay warm in winter and cool in summer, to keep our animals safe and our crops flourishing.

What happens when the temperature isn’t the actual temperature – when the humidity or wind speed are so high that they significantly change our personal experience of the weather?

What the air really feels like

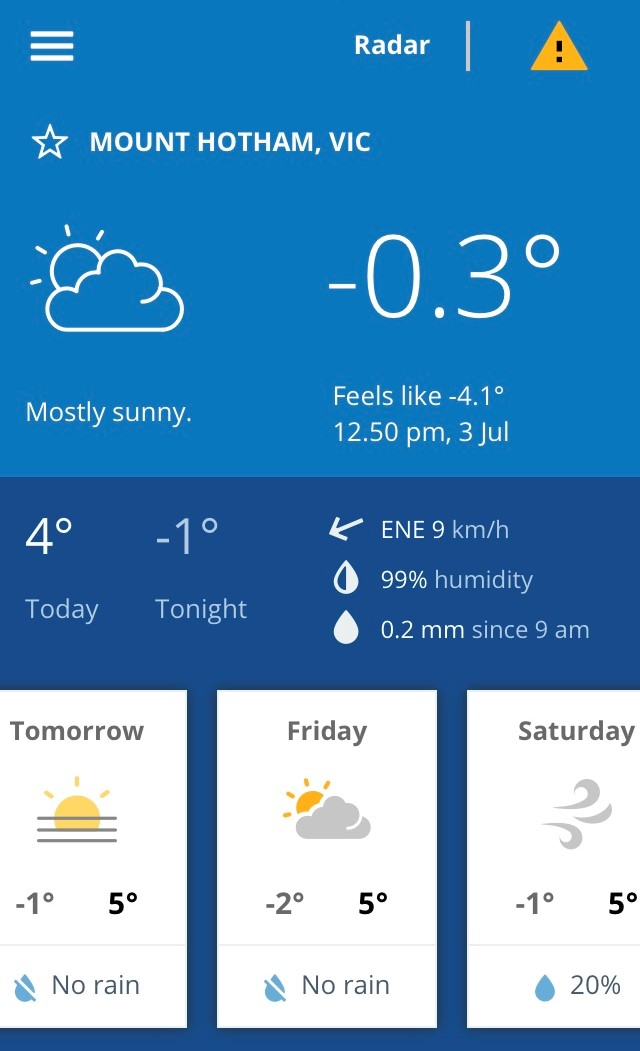

Up on Mount Hotham, a group of snowboarders is carving up Victoria’s newly coated alpine slopes when they decide to stop for lunch. They’ve checked the Bureau’s mobile website, and noted that the ‘air temperature’ is a chilly but bearable –1°C. But they’re in for a shock. With a 35 km/h wind blowing and low humidity, they soon become freezing cold. When one of them double-checks the website, they get the full story: ‘Feels like –11°C’.

|

On the other side of the country, beachgoers have been enjoying a sunny early summer morning in Perth. Locals know from experience that if they stay at the beach in the afternoon, they’ll begin to feel the chilling effects of the sea breeze. By 2pm, only the tourists are left on the beach. At the top end of the country, a group of intrepid hikers visits Kakadu National Park late in the wet season. Although the 29°C forecast that morning looked perfect for a lengthy hike, they didn’t count on the very high humidity, which prevents their sweat from evaporating and makes everyone extremely hot. Again, a quick check of the ‘Feels like’ temperature—an oppressive 38°C—could have spared the hikers much of their discomfort. In situations like these, it’s common—and entirely understandable—for people to simply think that the Bureau’s forecasters got it wrong. Left: Example of a much colder 'Feels like' temperature at Mount Hotham. |

||

Two distinctive temperatures

The Bureau has adopted the term ‘Feels like’ to describe exactly that: what the outdoor air feels like, as distinct from the actual air temperature. By checking both figures, you can make a much more informed decision about where you should go, what you can do, and what you should wear – especially if you’re going to be outdoors a lot, or somewhere that is particularly exposed to the weather.

Most of our air temperature readings are measured by thermometers in the distinctive white Stevenson screens that hold the instruments of our 600-plus automatic weather stations. These wooden boxes are fitted with slats that allow air to flow freely over the thermometers, but protect them from the sun and rain.

So while the Stevenson Screens provide accurate readings of the air temperature in the shade, they cannot tell you what that temperature actually feels like in their general location. This must be individually calculated according to local conditions, including wind speed, humidity and sometimes radiation from the sun.

The ‘Feels like’ temperature is a prominent feature of the BOM Weather app. In conjunction with the actual air temperature, wind and humidity levels, and three-hourly rain forecasts, the ‘Feels like’ temperature is another tool that mobile users can take with them anywhere—and double-check before they venture outside.

More information

The ‘Feels like’ temperature is also known as the ‘apparent temperature’, and was first described in the late 1970s to include the effects of sun and wind. A handy definition is available under the Temperature tab of our Weather Words glossary, which explains apparent temperature as ‘a measure of the discomfort caused to an appropriately dressed adult, walking outdoors, in the shade, by the current wind and humidity levels’. The Bureau's apparent temperature calculation does not include the effects of solar radiation.

A further definition is available on the Bureau’s glossary page, with links to ‘thermal comfort observations’ for major towns and regions across Australia. More detailed information about how weather factors affect human comfort is available on a special page about thermal comfort, along with tips and guidelines for working, playing and exercising safely in hot weather.

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.