Remembering Black Saturday: the extraordinary weather behind Victoria's 2009 bushfires

07 February 2019

The Black Saturday bushfires of 7 February 2009 were a devastating and historic disaster. They caused the deaths of 173 people and many more suffered the loss of their homes, with entire communities and huge areas of forest ravaged by flames. Record-breaking heat and unprecedented dryness combined with very strong winds set the scene for these horrific fires—and made them exceptionally challenging to fight.

Black Saturday dawned in an extreme heatwave, part of a longstanding and severe drought. An intense cool change later in the day was due to bring relief from the heat, but the wind associated with it would be extremely powerful—and where fires were burning, hugely hazardous. The predicted fire danger was literally off the charts—it exceeded the scale designed to measure it. Premier John Brumby warned that this would be, 'the worst day in the history of the state', with conditions even worse than those that preceded the terrible fires of Ash Wednesday (1983) and Black Friday (1939).

Image: After the flames: burned forest in Strathewen, Victoria, March, 2009. Credit: Mia Schoen

The long dry

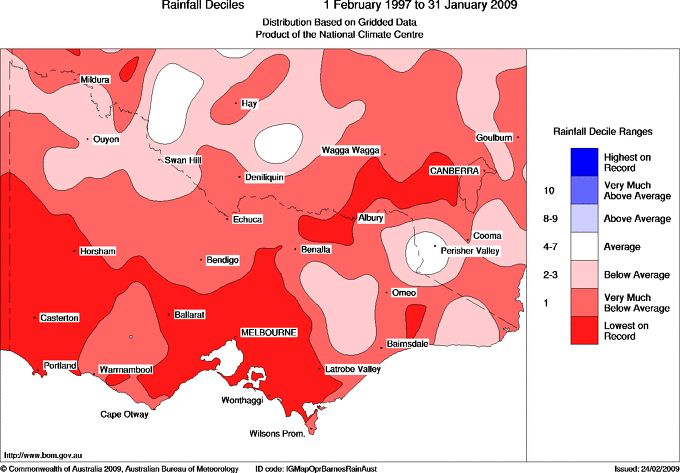

At the time of Black Saturday, southeast Australia had been in the grip of the merciless Millennium Drought for more than 10 years. Many parts of Victoria had received their lowest rainfall on record for a 12-year period and the loss of rainfall across the state over that time was equivalent to two whole years' worth of average rainfall. This was drought on a scale that Australia hadn't recorded before and the dryness of the landscape that resulted was a key ingredient in the cocktail of dangerous weather factors that contributed to the terrible events of the day.

Map: Rainfall for the 12 years preceding Black Saturday was the lowest on record for large parts of Victoria.

The long-term lack of rain was reinforced by very dry weeks leading up to the Black Saturday. Melbourne had seen no rain for 35 days—its equal second-longest dry spell on record. The city also had its second-driest January on record and its driest start to a year on record (with only 2.2 mm of rain to 12 February). A number of locations around Melbourne (including Preston and Ballarat), set new January records for low rainfall. Many places in Victoria's north and west of Melbourne, and in South Australia and southern New South Wales, had no rain at all that month.

The dryness of the landscape is one factor that influences fire danger. For Black Saturday, many predicted Forest Fire Danger Indices (FFDI) and Grass Fire Danger Indices (GFDI) were well over 100. The fire danger indices are based on fire-behaviour algorithms that use meteorological as well as fuel (forest or grass) inputs. They were originally designed with a scale of 0 to 100, where a rating of 100 was expected to be the worst conditions possible. Following Black Saturday, the indices were redesigned to create a new category for values of more than 100 (subsequently raised to greater than 150 for FFDI)—and so the 'Catastrophic' ('Code Red' in Victoria) fire danger rating was created.

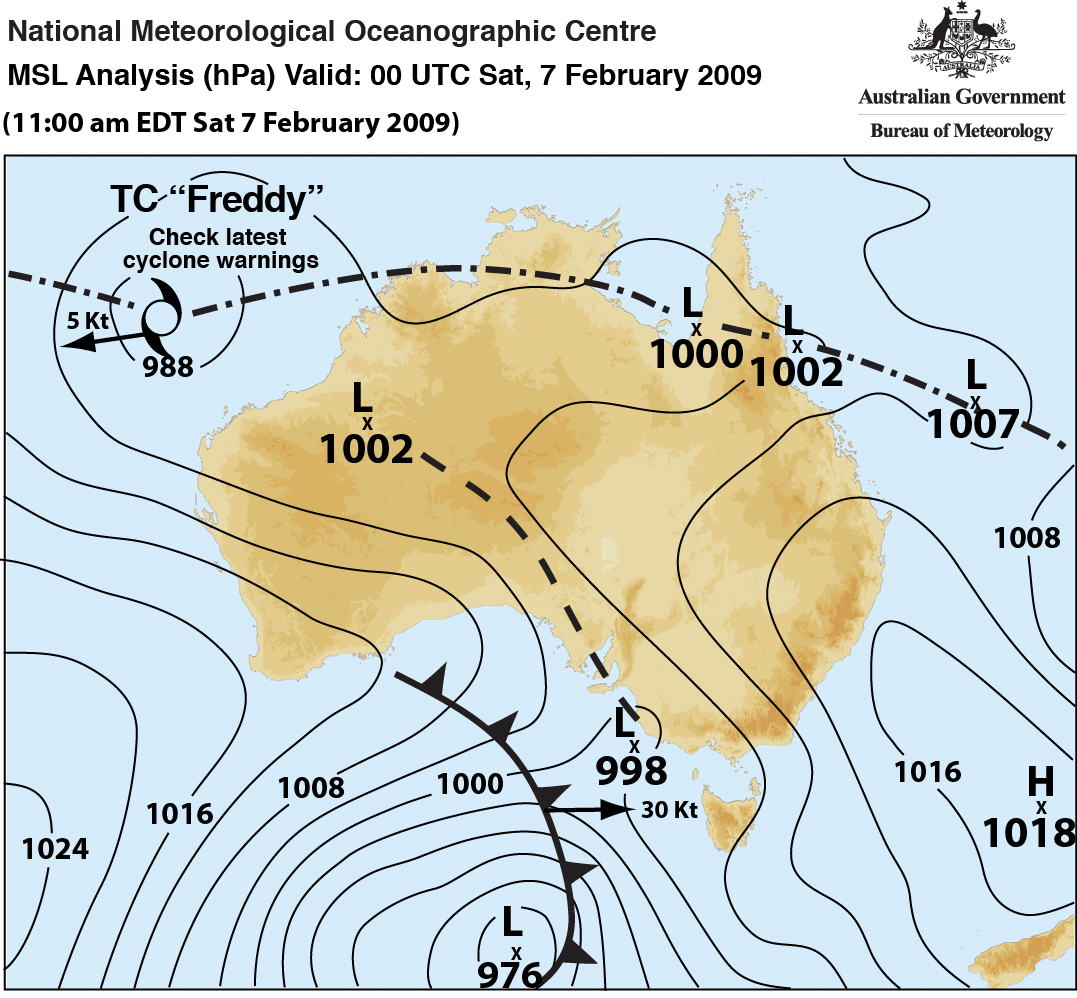

The searing heat

Across this long-term dry landscape rolled a long, blistering heatwave. This was remarkable heat, with many records set for high day- and night-time temperatures as well as for the duration of the heat. There were two 'pulses' of exceptional high temperatures (28–31 January and 6–8 February). Temperatures in between those dates were slightly lower near the coast, but still very high inland. The reason for the heat was the combined effect of three meteorological features happening at once: a slow-moving high pressure system in the Tasman Sea, an intense tropical low off the northwest coast of Western Australia and an active monsoon in the north. These were the ideal conditions for hot air from the tropics to be directed to the south. The heatwave culminated in record high temperatures across most (more than 87 per cent) of Victoria on 7 February, before the high in the Tasman Sea moved away the next day.

Chart: The synoptic chart from Black Saturday shows the intense low pressure system off Western Australia (by now tropical cyclone Freddy), the monsoon trough (dotted line running from the cyclone across the Top End and Cape York Peninsula and the high pressure system in the Tasman Sea. You can also see the strong cool change in the Great Australian Bight (the bold black line with 'teeth'), and a pre-frontal trough (dashed line) extending from northwest Western Australia through to southeast South Australia, moving across from west to east.

On Black Saturday most of northern Victoria and large parts of central Victoria sweltered through maximum temperatures above 45 °C, with only small areas near the coast and at higher elevations failing to top 42 °C. An all-time Victorian record was set at Hopetoun, in the northwest, where the temperature reached 48.8 °C. With meteorological records more often broken by tenths of a degree, this was a huge leap from the previous record of 47.2°C (Mildura, 1939). In fact, Hopetoun saw the highest temperature ever recorded in the world this far south. Eight other sites, in the Mallee, Wimmera and in the area immediately west of Melbourne, also broke records.

Many all-time records were set in Victoria that day, including Melbourne (154 years of record), where the temperature reached 46.4 °C, exceeding the previous record of 45.6 °C, set on another terrible day, Black Friday (13 January) 1939. It was also a full 3.2 °C above the previous February record, which was set in 1983—this is an extraordinary margin for a site with such a long record. Geelong (47.4 °C) and Wilsons Promontory (42 °C) were among long-term sites that broke all-time records which had been set only the previous week.

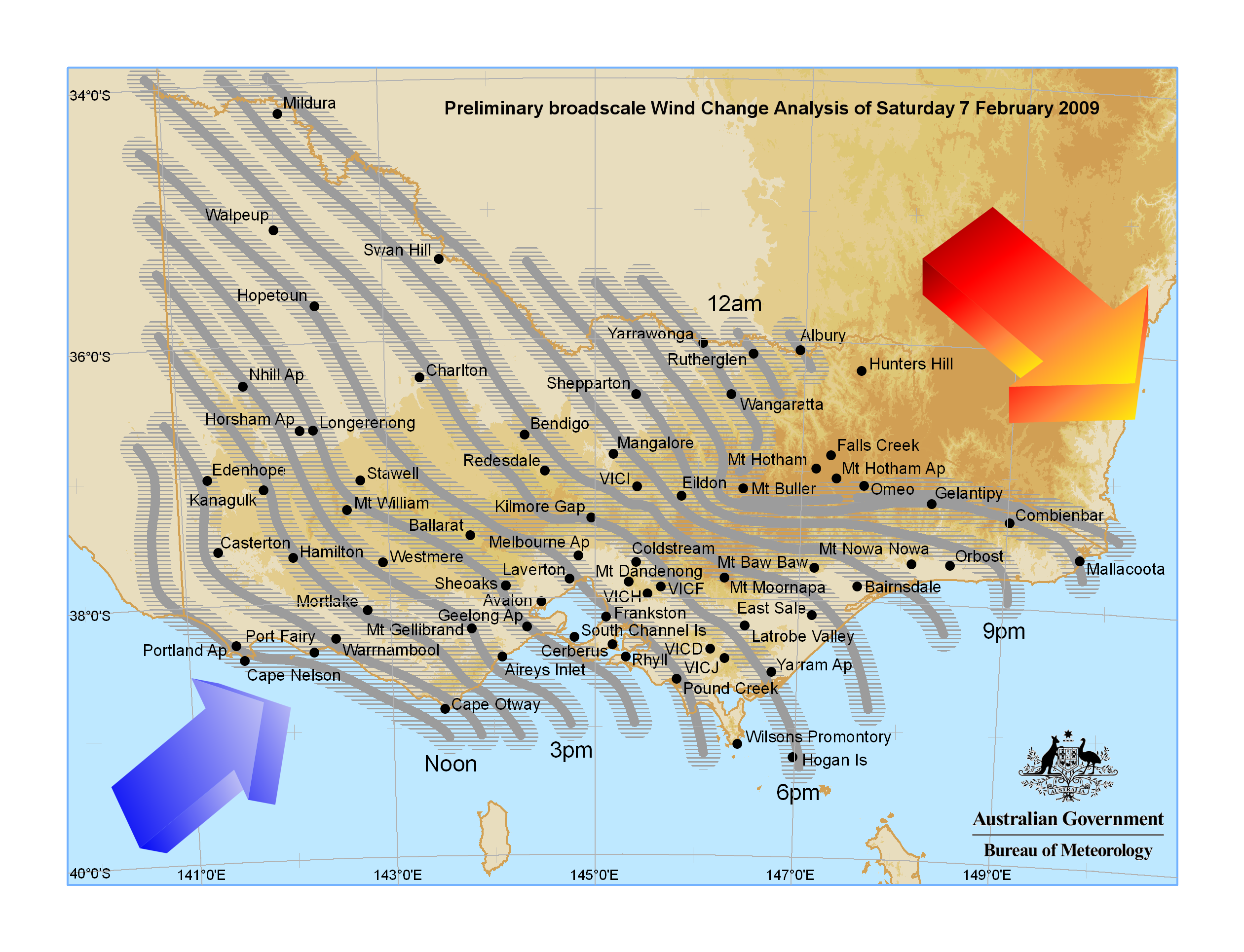

The driving wind

There was very strong to gale-force wind all day on Black Saturday, both ahead of the change and behind it. This had a catastrophic impact on the fires. The northwesterly wind ahead of the change drove fires ahead of it, and the southwesterly wind behind the change hit those relatively long and narrow bands of flame broadside on, opening up massively wide fire fronts on their eastern flanks that moved at terrifying speed. Some fires also created their own thunderstorms (a phenomenon known as pyrocumulonimbus), sparking lightning that is likely to have created new fires.

Black Saturday's near-constant strong wind was remarkable, even in the context of other fire disasters. Historical records suggest that on Black Friday the northwesterly winds were of comparable strength to Black Saturday, with those behind the change weaker, while on Ash Wednesday the southwesterlies after the change dominated.

In some ways, meteorologically speaking, this wind change was ‘business as usual’. It’s a characteristic weather pattern in the region to see hot northwesterly winds shift to cooler southwesterlies. However, this particular change moved unusually quickly. A standard southwesterly change moves from Port Fairy to Melbourne in about seven hours. On Black Saturday it took less than five.

It didn't take long for Black Saturday's weather to establish itself. By 11 am there was a hot wind blasting from the northwest, recording speeds at Mt Gellibrand of 87 km/h (near storm force). Temperatures were already near 40 °C in many places and relative humidity was below 20 percent. By the early afternoon, average wind speeds of 40–60 km/h were being reported in many areas and fire danger had risen to extreme in almost the whole State. Meanwhile, in the far southwest, a strong, gusty, southwesterly change was moving through, dropping temperatures and increasing humidity.

The wind didn't let up. By 5 pm, gusts to 115 km/h were recorded at Mt William and Mt Gellibrand, and gusts over 90 km/h were occurring in a number of other places. Fire danger remained extreme (it didn’t drop until up to an hour after the change in parts of central Victoria). Thunderstorms formed with the change as it rolled through, but also in the smoke plumes above fires east and northeast of Melbourne. By 8 pm lightning from these storms was very active—it would also start in Gippsland as the night wore on.

By 11 pm the change had moved out of Victoria in far east Gippsland. In the northeast it had weakened and reached Wangaratta, but it didn't extend to greater altitudes in the alps. The northwesterly winds ahead of the change had finally slowed, but temperatures remained in the mid- to high 30s. In Melbourne, winds had become light and variable, and temperatures rose slightly again—not what you’d usually see at that time of night and after this type of change. It took 3–4 hours before the general southerly wind overwhelmed the variable wind flow and allowed a second southerly surge through the city and west Gippsland, dropping temperatures.

Diagram: The grey lines show the approximate times the the wind change reached various places across Victoria during Black Saturday. Locations labelled 'VICD, VICF' etc were portable automatic weather stations used by fire agencies to provide data close to fires. The red arrow shows the direction of the wind before the change and the blue arrow shows its direction after the change.

The Bureau’s role

Our meteorologists worked closely with emergency managers on Black Saturday, and in the days leading up to it—as they do during and prior to all severe weather events. They issued forecasts and warnings to the public, briefed authorities and emergency managers, supplied information and interviews to the media and provided specialised advice such as detailed spot forecasts and wind-change information for fire-fighting purposes.

You can read more about how the Bureau works with emergency management in this blog, about our meteorologist embedded in Victoria's State Control centre.

In the case of Black Saturday, we also provided detailed information about Black Saturday's weather to the 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission, in its inquiry into the tragedy.

More information

Line of fire: How a catastrophe unfolded (ABC)

What makes a horror fire danger day? (ABC)

Black Saturday: The bushfire disaster that shook Australia (BBC)

Bushfires in Victoria: 7–8 February 2009

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.