Explainer: avalanches

18 June 2020

Avalanche risk can be underestimated in Australia due to our relatively flat and dry landscape. But avalanches can and do occur in our alpine regions, sometimes with devastating consequences. So, what causes avalanches, when are they most likely, and how can you tell if there's an elevated risk if you're heading to the snow?

What's an avalanche?

An avalanche is a rapid flow of snow down an inclined slope such as a mountainside or even the roof of a building. Although we're focusing on snow avalanches here, they can also comprise rock, ice, soil, or other materials—in which case they're called landslides.

Avalanches vary greatly in size. In North America, they use a size scale of:

- 1—small slides generally not deep enough to bury a person;

- 2—enough to bury a person;

- through to 5—major snow avalanches that could bury or destroy a village.

The avalanches we see in Australia are usually size 1 or 2 on this scale. This is mostly due to the amount of snow we get, which typically reaches 1–2 m in depth.

Image: Avalanche on Etheridge Ridge, near Mount Kosciuszko. Credit: Alpine Access Australia. In August 2019, a series of cold fronts dumped a metre of snow across Australia's alpine regions in a relatively short period. This led to an elevated risk of avalanches.

What causes avalanches?

Avalanches can be triggered by natural forces, such as the pull of gravity on a steep slope or warming temperatures destabilising the snowpack. They can also be caused by human activity, such as the load of a skier across the snow, or explosives as part of avalanche control. They can occur when one layer of snow slides off another (surface avalanche) or the entire snow cover slides on the ground (full-depth avalanche).

Avalanches are typically only a concern in Australia’s alpine regions. These are the southeastern mountain ranges of New South Wales and Victoria (1200 m or more above sea level) and in the Central Plateau of Tasmania (900 m or more above sea level).

What factors make avalanches more likely?

There are a number of factors that lead to an increased risk of avalanches, although they don't guarantee one will happen.

Snow layers with different compositions

As snow falls during the season, the snow accumulation (or snowpack) is made up of different layers. The physical composition (thickness, density and crystal type) of these layers can vary within the snowpack, as they're affected by weather conditions when the snow is falling, as well as after it has accumulated. This changes the structures of the ice crystals in the snow. We see layers with different compositions when:

- fresh snow falls on snow that has recently melted and re-frozen as a slippery, icy layer;

- fresh snow has freezing rain or 'graupel' (soft hail or snow pellets);

- 'surface hoar' (a type of feather-like frost on the snow) develops with fresh snow falling on top, which creates a weak air-filled layer; or

- snow within the snowpack changes with ice crystals becoming rounded or developing into facets, creating weaker layers.

In these cases, the layers may have weaker bonds with each other than usual, meaning the snowpack has greater instability.

Large accumulations of snow

Avalanches are most likely to occur after a fresh dump of snow, particularly large amounts in a short time. The snowpack may become overloaded by the weight of the new snow, setting off an avalanche. The risk increases even more if new snow is falling on top of an icy layer or surface hoar, which makes it difficult for the fresh snow to bond to the older layers below.

Large and unstable accumulations of snow may also happen on the sides of rooftops and other sloped surfaces.

Wind

Wind can transport falling snow or surface snow. These deposits can be much larger than the amount of snow falling and can form a wind slab, most commonly on 'lee' slopes, which are oriented away from the wind (and therefore more sheltered, allowing the snow to deposit). An avalanche can occur when this slab overloads a weak layer underneath.

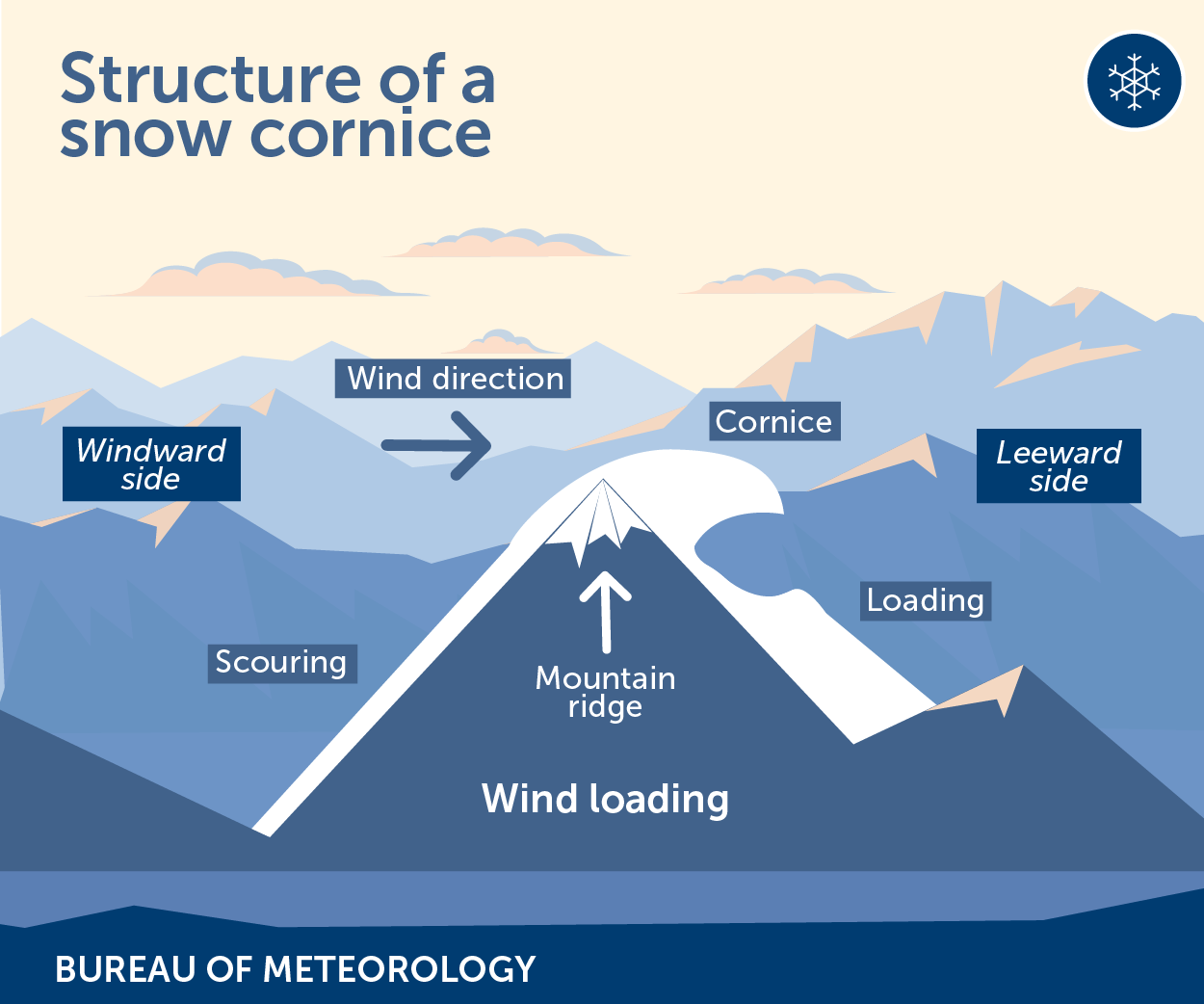

Wind can also form unstable snow features such as 'cornices'—an edge of snow, often overhanging, on a ridge or crest of a mountain or sides of gullies. While they can be beautiful, cornices can also collapse unexpectedly.

Illustration: Structure of a cornice.

Sun exposure

Sun exposure increases avalanche risk by changing the temperature gradients in the snow layers, which causes instability. As it warms up, the snow layer can break, particularly at its shallow points. Caution should be taken during springtime or unusually warm bursts during winter, as the layers can also release as a wet slab of snow.

Terrain

Terrain plays a central role in avalanches, particularly in relation to:

- angle of the slope: there's a risk of avalanches on any slope over 28 degrees. Wet slides can occur at even lower angles.

- slope aspect: a north-facing slope may be more unstable than a south-facing slope since it has sun exposure to melt the snow. Lee slopes are more likely to have wind slabs.

- surface type: some slopes can be self-supporting (concave) while others hold more tension (convex). If you can't see over the edge then you are on a 'convexity', and there may be an increased risk of avalanche.

- Surface features: elements such as trees and rock outcrops can act as anchors, or alternatively, create trigger points for avalanches by creating a different temperature gradient in the snowpack.

Image: Snow cornice above Lake Cootapatamba, NSW.

When do they usually occur?

Avalanches can happen at any time of year when there's a snowpack, typically winter and spring in Australia.

Importantly, they can occur when the weather is sunny, often referred to as 'blue bird' skiing days. The weather system that led to instability in the snowpack (for example a large fall of fresh snow) may have passed, but the risk remains for days or weeks afterwards. Skiers and boarders should allow sufficient time for the new snow to bond to existing layers and understand how to assess the risk of not just avalanches but other hazards posed by blizzards, ice or reduced visibility.

Where can I find out about avalanche risk?

Although Australia doesn't have an avalanche forecast or warning service, there's a lot of useful information to help you reduce your risk when venturing outside of patrolled ski areas.

Watch for mentions of avalanche risk in any communications from park operators (e.g. NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, Parks Victoria), ski resorts, emergency services, or recreation organisations such as the Mountain Sports Collective who collect observations on the state of the snowpack and conditions in the backcountry.

Keep an eye out for weather conditions that could increase the risk of avalanche.

What actions should I take?

Australia's snow resorts monitor and mitigate avalanche hazards within their boundaries. However, if you're skiing or snowboarding in resorts, it's important to be aware of avalanche risk as conditions can change quickly.

If you're undertaking activities in backcountry areas, we recommend you:

- make conservative decisions when choosing the terrain to travel and ski on if avalanches or the conditions that lead to them are possible

- bring the right equipment (transceiver, shovel, and snow probe) and know how to use it (by doing an avalanche safety training course)

- never go out alone, and let someone know where you're going and when you'll be back.

Image: Avalanche awareness training. Credit: NSW SES Alpine.

More information

- Know your weather: skiing and snowboarding

- Don't be left out in the cold—weather safety in Australia's alpine regions

- BOM Weather Guide: Snow (short video)

- Snow alert: How to make sure you stay on top of the snow this ski season

- Winter weather: what you need to know

- NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service: alpine safety

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.