Amazing weather photos: art and science join forces

09 November 2021

It's weather as you may never have seen it before. A year's worth of unusual, creative or rarely photographed weather sights. These spectacular photos are the winners of our competition and feature in the 2022 Australian Weather Calendar. Find out what's happening in the atmosphere to produce these fascinating and beautiful displays.

Spectacular auroras

Image: Aurora australis over Davis station meteorological office, Antarctica. Credit: Barry Becker

Barry Becker was in Antarctica working for the Bureau when he took this photo. He overcame challenging conditions to share an amazing sight most people will never see with their own eyes.

The glowing green light shown here is a space weather phenomenon called aurora australis or the southern lights. Auroras are the result of events that begin on the Sun. The Sun is so hot that high-energy plasma (a gas of electrically charged particles) can escape from its gravitational field. As the plasma approaches Earth, it can interact with the planet's magnetic field, accelerating charged particles towards the north or south poles. Upon entering the atmosphere, they collide with atoms and trigger light emissions.

The aurora's colour is influenced by how energetic the collisions are, where they happen in the atmosphere, and which atoms and molecules are involved. Oxygen releases greenish-yellow or red light, while nitrogen releases dark red or blue light.

Image: Aurora australis from Norring Lake, Wagin, Western Australia. Credit: Grahame Kelaher

Grahame Kelaher drove for 3 hours and slept in his car to capture this beautiful aurora, resplendent in mauve, pink and green.

The multicoloured light shown here is the aurora australis or southern lights. It's a common sight in Antarctica that's sometimes also visible from Australia, as in this photo. Where you can see the aurora depends on the size of the space weather storm that causes it. The more intense the storm, the further away from the pole the aurora is visible. This aurora on 23 June 2015 was caused by one of the larger storms of the solar cycle.

Another factor that affects aurora viewing is how much light is around. Ideally you need to be standing on a dark beach or hill, on a clear night, with an unobstructed view to the south.

More about auroras:

Powerful thunderstorms

Image: Supercell thunderstorm, Gympie, Queensland. Credit: Bet Wright

Gympie sees plenty of storms. The weekend Bet Wright captured this menacing example she watched 3 storms come in.

Thunderstorms can happen at any time of year, but in Queensland, where this photo was taken, they're most common from September to March. The frequency of storms during this period is primarily due to the increase in energy from the sun during the warmer months, and extra moisture coming in from the sea. Both are critical ingredients for huge storms like this supercell thunderstorm.

A supercell is a particularly strong, long-lived type of thunderstorm. They can sustain themselves for many hours and cause huge amounts of damage. The rotating base seen here is a clear giveaway that it's severe and a sign that potentially dangerous conditions were on the way.

That was certainly the case with this storm, that battered south-east Queensland on 1 December 2016. It brought very strong winds, heavy rainfall and in some areas, hail up to the size of tennis balls. It caused damage to properties and many houses lost power.

Image: Afternoon thunderstorm, Gunn Point, Northern Territory. Credit: Louise Denton

Louise Denton took an afternoon drive out to Gunn Point from her Darwin home and 'got lucky' with this beautiful storm and sunset.

In the tropical Top End of the Northern Territory, where this photo was taken, the seasons are broadly categorised into the 'dry' and the 'wet'. However, the Larrakia people in the Darwin region observe 7 main seasons. These recognise both changes in the weather and changes in the local plants and animals.

Afternoon thunderstorms like this one are common during the wet season, which typically begins in October and runs until the end of April. The wet season is also the tropical cyclone season. The warm waters around the Top End provide the fuel to form and sustain these severe systems.

More about tropical seasons: The wet and the dry: seasons in the tropics

More about thunderstorms:

Isolated downburst

Image: Downburst seen on descent into Normanton, Queensland. Credit: Will Long

Will Long had a birds-eye view of this isolated downburst, complete with rainbow. He took the photo from the cockpit of the plane he was flying from Mornington Island to Normanton.

Downbursts are localised areas where air, and sometimes rain, descend rapidly from thunderstorms or heavy showers. As the developing rain or thunderstorm cloud rises vertically, strong updraft winds lift raindrops and hail high into the atmosphere. When the updraft can no longer support the weight of the rain core, it quickly falls back down. It gains speed and strength as it falls, then spreads out at the surface.

This smaller downburst (called a microburst) in Normanton wasn't too much cause for concern. But downbursts can cause damage to aircraft. The stronger the updraft, the stronger the wind and rain coming back down.

Whirling dust devil

Image: Dust devil near Whim Creek, Pilbara, Western Australia. Credit: Coral Stanley-Joblin

Coral Stanley-Joblin was on a storm-chasing holiday when she spotted this mighty dust devil twisting above red-dirt country in the Pilbara.

Dust devils, or willy-willies, form when a localised pocket of hot air rises quickly through cooler air above it. This can happen on hot, clear and calm days. The rapidly rising air is replaced by air rushing in below it. The inflowing surface air often arrives in an uneven manner and can start to rotate. As the air pocket continues to rise and stretch vertically, the speed of rotation increases. It's the same way a twirling ballet dancer spins faster as they draw in their arms and legs. In dry areas, dust is drawn into the rotating air column, giving dust devils their name and distinctive appearance.

Dazzling lightning

Image: Lightning strike near Forster, New South Wales. Credit: Cliff Gralton

Cliff Gralton watched this storm grow on the radar in the BOM Weather app. Then he headed out and photographed lightning so bright it illuminated the surrounding landscape.

When photographing lightning, timing is everything. A sudden burst of light and sound, and in the blink of an eye it's gone. This shot of cloud-to-ground lightning was taken during a summer storm outbreak in January 2021. These storms brought large hail and intense winds to the region.

How often you experience a thunderstorm depends on where you live in Australia. Hobart is the least lightning-prone capital city, with an average of around 5 thunder days per year. Sydney sits around the 20–25 mark. But the clear winner is Darwin. Its residents normally see more than 80 thunder days per year, concentrated around the wet season (October to April).

Image: Lightning over Mt Coot-tha, Brisbane, Queensland. Credit: Chris Darbyshire

Chris Darbyshire loves to chase storms near and far, but he captured this breathtaking sight from his Brisbane balcony.

Lightning is one of nature’s most spectacular displays, but it can also be spectacularly dangerous. The high-voltage show seen in this photo is caused by negatively charged channels leaving the cloud, attracted to positively charged objects at the surface. The flash of light we see is the return stroke as the current heads back to the cloud.

It's a common misconception that lightning always strikes the tallest object. Lightning currents prefer the path of least electrical resistance so favour taller, metallic structures, like these transmission towers. However, surrounding objects may also be struck.

More about lightning: A bolt from the blue: what is lightning?

Extraordinary clouds

Image: Mammatus clouds, Daylesford, Victoria. Credit: Martina Nist

Martina Nist was urgently summoned from a Sunday morning sleep-in to get out of bed and take a look at the sky. It was well worth it to see these extraordinary clouds.

Mammatus clouds appear as sagging pouches of sinking air which hang from the underside of a parent cloud. They indicate instability in the atmosphere. They're distinctive in that they're formed from downward motion, while most other clouds are formed from upward motion.

Mammatus are usually associated with cumulonimbus (thunderstorm) clouds. They can be a sign that that the storm is particularly intense. The classic example in this photo was captured on the wild morning of 15 November 2020. Storms that day caused damage across the region.

Image: Asperitas clouds, Strathgordon area, Tasmania. Credit: Dotan Beck

Dotan Beck had been traveling in Australia for 3 months in his van. On his last sunrise in Tasmania he captured this stunning image.

This rare, lumpy-looking blanket of cloud is known as asperitas and it's a relative newcomer to classification. It was added to the World Meteorological Organization's International Cloud Atlas in 2017. The cloud's full name is altocumulus stratiformis opacus asperitas. Altocumulus refers to the height and cloud type – cumulus cloud in the middle level of the atmosphere. Stratiformis indicates it has formed in a layer. Opacus means it's thick enough to mask the sun. Asperitas, from the Latin for roughness, refers to its wave-like appearance.

More about clouds:

Drifting salt dust storm

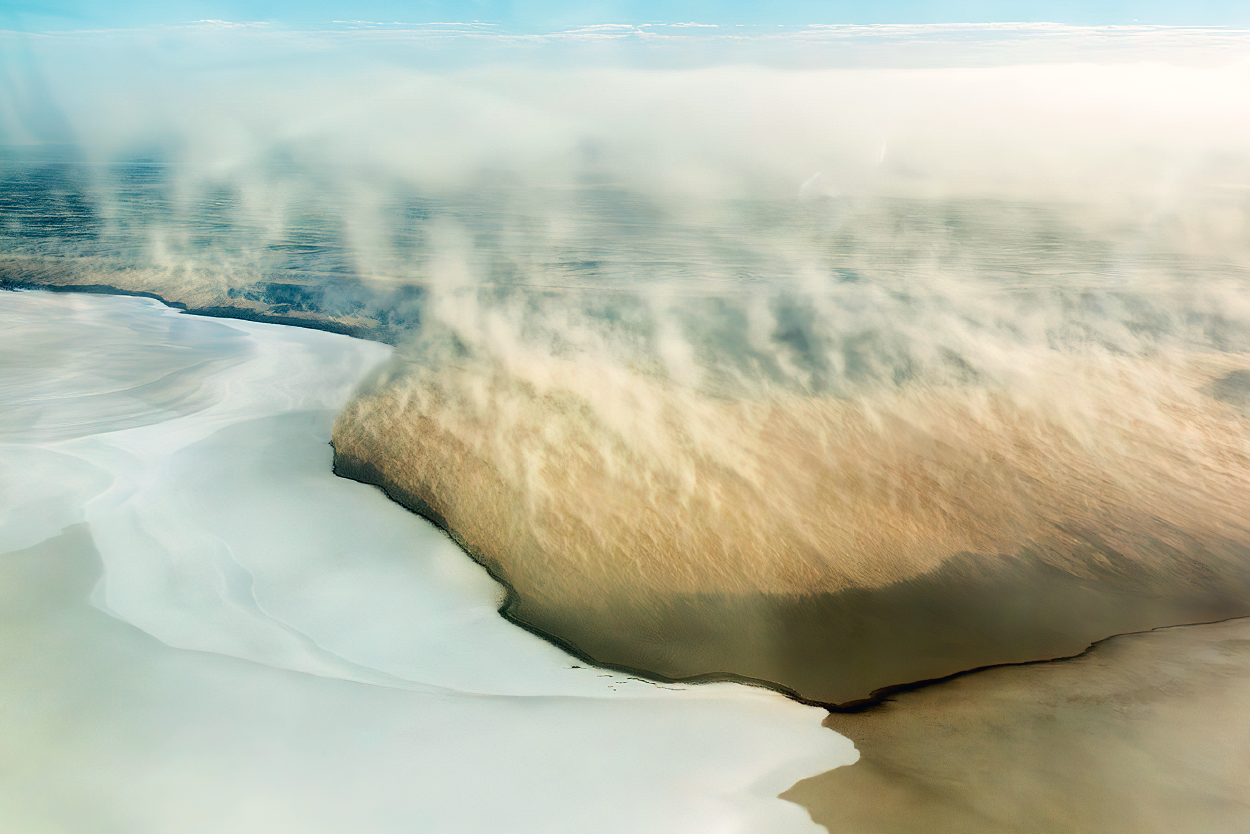

Image: Salt dust storm, Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre, South Australia. Credit: Cathryn Vasseleu

Cathryn Vasseleu took a scenic flight over Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre in 2019. That's where she saw this rare and beautiful scene of raised salt drifting over the lake.

Dust storms are common throughout arid Central Australia. Sometimes they can even make their way hundreds of kilometres to cities near the coast. Salt storms, like the one in this photo, are caused in a similar way to dust storms, although they're much less common. An expansive area of dry salt is needed, and there are relatively few such sources. Strong and gusty winds pick up the salt and raise it into the atmosphere to create a milky cloud-like expanse. Salt particles tend to be much larger than dust. This makes them harder to lift and transport across the continent like dust storms.

In 2019 heavy rain in Queensland the Northern Territory made is way south over several months, gradually filling Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre.

More information about Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre filling: Queensland floods: the water journey to Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre.

More about dust storms: Explainer: what is a dust storm?

Wind-blown rime ice

Image: Rime ice on vegetation, Mt St Phillack, Baw Baw National Park, Victoria. Credit: Jason Freeman

Jason Freeman captured this beautifully detailed 'frozen moment' while cross-country skiing between Mt St Gwinear and Mt Baw Baw.

Rime ice forms when supercooled liquid water droplets in the air freeze on contact with exposed surfaces. It occurs during periods of freezing fog, mainly across alpine regions during winter.

These are different weather conditions from those that cause frost. It usually requires clear, calm nights to form.

The shape in which rime ice freezes tells us about the weather conditions at that time. In this example the ice has formed in the direction the wind was blowing, creating a mini wall of ice behind this plant.

Crashing waves

Image: Large swell along the coast near Port Campbell, Victoria. Credit: Andrew Thomas

When Andrew Thomas saw the Bureau forecast for large swell, he jumped into his car and drove for 2 hours to take this evocative photo.

Wind is the main cause of waves. Waves caused by local weather conditions are called sea waves. As they move away from the weather system that caused them, their appearance changes and we call them swell waves. Swell waves, like the ones in this photo, play a big part in shaping Australia's constantly evolving and eroding southern coastline.

The large expanse of the Southern Ocean allows winds to blow over a long distance of water, called the 'fetch'. The longer the wind blows over the water, the more energy is transferred, allowing bigger swell waves to develop. When these waves crash into the shore, all that energy needs to go somewhere, so it goes up.

More about waves: Explainer: dangerous ocean waves

You may also be interested in

Buy the 2022 Australian Weather Calendar

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.