Don't be left out in the cold—weather safety in Australia's alpine regions

08 June 2017

Our alpine regions are some of the most beautiful parts of Australia. Yet the features that attract visitors—stunning mountains and snowy landscapes—mean activities there are very exposed to hazardous weather. Understanding alpine weather can help you to be better prepared, or change your plans, for a safer and more enjoyable visit.

Australia's alpine regions

Most of Australia’s alpine regions are along the southeastern mountain ranges of New South Wales and Victoria (1200 m or more above sea level) and in the Central Plateau of Tasmania (900 m or more above sea level).

Snow can fall in alpine regions all year round. In fact, there has been a white Christmas several times since records began—most recently in 2006 when 15 cm of snow was recorded over the Australian Alps. Snowfall in Australia is dependent on cold-air outbreaks coming from the Southern Ocean and can be influenced by Australia’s climate drivers. The snow can be notoriously fickle, with some years bringing deep cover and others amounts that barely cover the grass.

Image: Alpine National Park, Victoria

Peak tips for alpine weather safety

- Outdoor activities in alpine regions are very susceptible to the weather—use caution all year round.

- Always check the weather forecast before you go out into alpine regions.

- Keep a watch on the weather while you're out, as conditions can deteriorate quickly.

Watch out, hazards about

The higher altitude and mountain terrain of alpine regions bring with them a range of hazards. Whether you're skiing, snowboarding, bushwalking, driving or just out and about in alpine regions at any time of year, watch for these hazards.

|

Hazard |

Potential impacts |

|

Blizzards—violent and very cold wind loaded with snow |

Reduced visibility makes it easier to lose your bearings, even if you're familiar with the area. White-out conditions (uniform whiteness) in a snowy landscape can take away all reference points. |

|

Heavy snow |

Reduced visibility of paths, signs and hazards makes travelling, navigation and/or rescue difficult. Large snow accumulations may slip off rooftops, or cause trees or their limbs to fall. Increased risk of hypothermia, especially if snow combines with wind. Compacted snow and ice on roads increases risk of accidents. Increased avalanche danger. |

|

Heavy rain |

Water levels in creeks and rivers can rise quickly with sudden downpours. Slippery terrain and roads increase risk of accidents. Increased risk of hypothermia, especially if rain combines with wind. |

|

Strong wind, particularly at high points and exposed places |

Walking, skiing and staying upright can be difficult or impossible. Trees or large limbs may fall. Heat is carried away from the body at an accelerated rate, lowering body temperature. Infrastructure and equipment (such as tents) may be damaged. |

|

Fog and low cloud |

Reduced visibility of reference points makes navigation and driving difficult. White-out conditions can occur when combined with a snowy landscape. |

|

Cold temperatures and wind chill |

Prolonged exposure can result in hypothermia and/or frostbite. Wind can make the air temperature feel even colder on exposed skin (wind chill). |

|

Ice |

Walking, skiing or driving may be extremely dangerous, with loss of grip leading to accidents. Black ice (a thin, clear ice coating on road surfaces) can be very difficult to spot, increasing accident risk. |

|

Lightning strikes, particularly at high points and exposed places |

Injury or death from being struck by lightning. |

|

Strong UV levels, particularly when reflected off the snow, and at altitude |

Damage to skin (sunburn) and eyes (snow blindness). Cool temperatures can lead to people underestimating UV levels. |

Image: Kosciuszko National Park, New South Wales

What about snow in non-alpine regions?

Cold fronts can bring heavy snow to non-alpine regions, causing disruption and creating dangerous conditions for outdoor activities and driving. While the amount of snow is often small overall, it can fall to low levels, even down to the coast. On 28 June 1836, snow 2.5 cm deep covered the streets of Sydney!

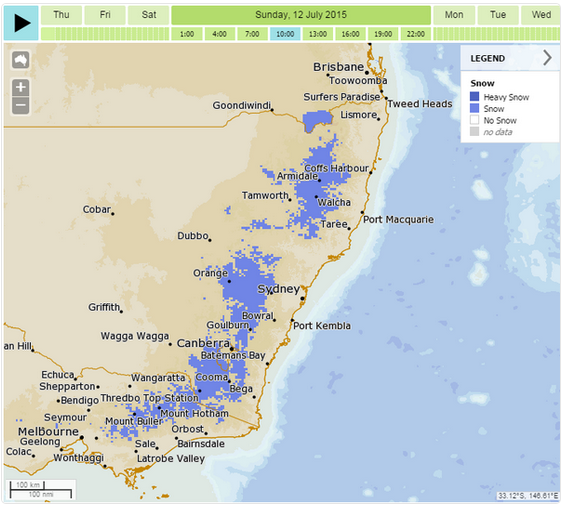

More recently, a series of strong cold fronts in July 2015 brought widespread snow to non-alpine parts of southeastern Australia. The extent and depth of snow was highly unusual and resulted in disruption at several major centres from west of Sydney to southern Queensland. Find out about the 2015 snow event and 100 years of significant weather events in NSW.

Image: MetEye snow forecast 12 July 2015

Where to find alpine weather information

Australian Alps Weather webpage—forecasts and observations for locations within this region. Watch for this symbol in forecasts, indicating snow:

![]()

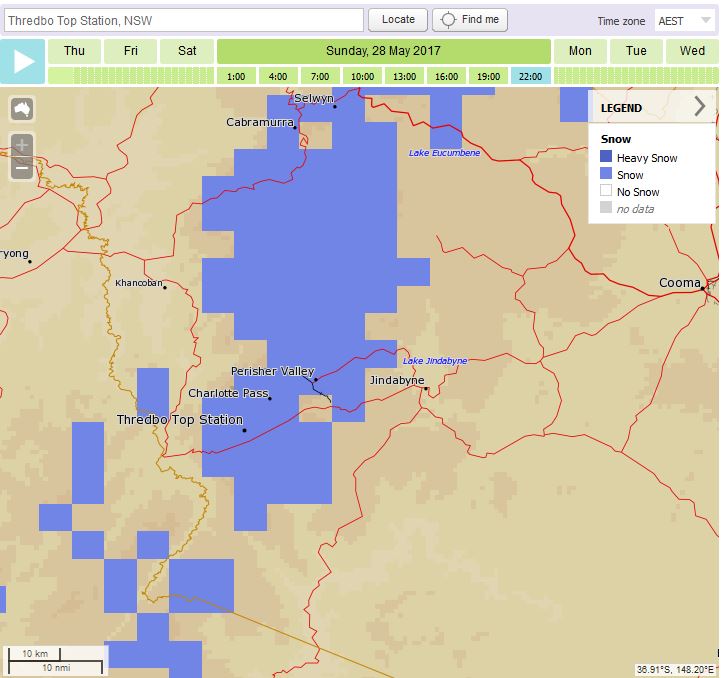

Online tool MetEye—detailed snow forecasts showing where snow is possible at any specific location over three-hour intervals during the next seven days. Read about using MetEye for snow forecasts.

Image: MetEye snow forecast (28 May 2017)

Snow depth

The Bureau does not provide observations of snow depth. Snow depth is difficult to measure because snow density varies greatly from place to place. Snowy Hydro has long-term weekly snow depth measurements from a number of sites, with the longest record at Spencer's Creek (measurements since 1954). Many resorts also record snow depth within their ski areas.

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.