Explainer: how is rain forecast?

11 February 2020

'Is it going to rain?' It's one of the most frequently asked questions of our meteorologists, and rain is one of the most challenging weather elements to predict. So, how does the Bureau forecast rainfall, and how will you know whether to pack an umbrella—or batten down the hatches?

What causes rain?

Clouds are simply millions of tiny water droplets suspended in the air. These tiny water droplets form when the water vapour in the atmosphere cools and condenses. Cooling of the water vapour in the atmosphere occurs when air is forced to rise.

Mechanisms to make air rise include broadscale systems such as cold fronts and tropical cyclones leading to large cloud masses. Showers and thunderstorms from small (less than 10 km in diameter), isolated clouds formed by local effects also cause this.

Once the cloud forms, the droplets collide with each other and grow. They eventually become too heavy to remain suspended in the air, and so they fall to the ground as rain. The process by which droplets merge is known as 'coalescence'.

Image: The nature of thunderstorms means rainfall can be very isolated. Thunderstorm near Windorah, Queensland. Credit: Australian Sky & Weather.

Types of precipitation

Generally, we see two types of precipitation: convective and stratiform. Convective precipitation is usually associated with showers and thunderstorms—often producing those isolated bursts of heavy rainfall.

Stratiform precipitation on the other hand is usually light to moderate, and associated with stratiform 'layer' type cloud found in the low and middle levels of the atmosphere. Stratiform clouds tend to produce uniform, widespread rainfall—you'll often see this type of rain with cold fronts and northwest cloud bands, for example.

Forecasting rainfall amounts

To work out the amount of rainfall, computer models and forecasters use 'precipitable water', which provides information about how much water vapour is available in the atmosphere for any approaching weather systems to draw in. Precipitable water is measured using information from weather balloons and water vapour imagery from weather satellites.

Our weather models forecast precipitation guidance at 3 or 6 hourly intervals, indicating the areas where rain might fall, and how much. We look at a number of different models and if they're all in consensus, this gives us more confidence in rain happening. However, if they're showing different scenarios, this gives us less confidence.

In very basic terms, high values of precipitable water occur when the atmosphere is warm and moist, and high precipitable water values can lead to heavy rainfall totals, such as those in northern Australia in summer.

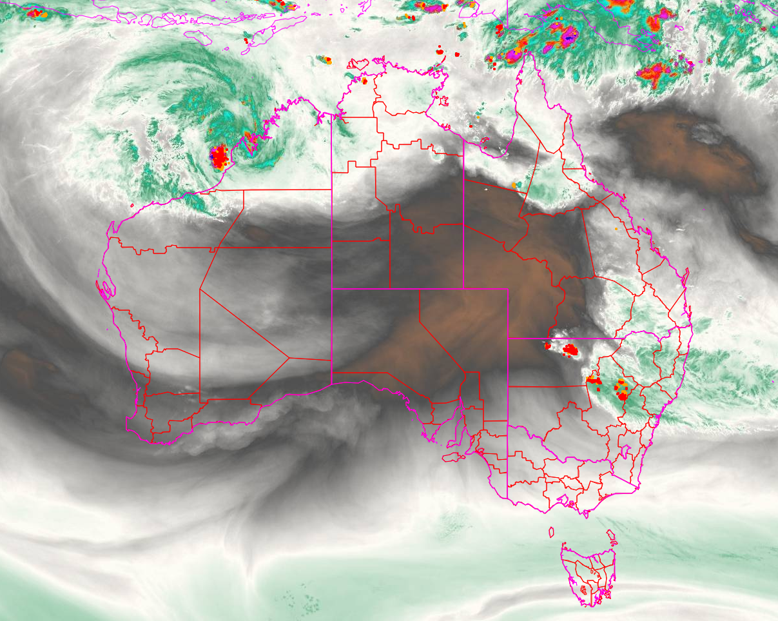

Image: Satellite imagery showing water vapour in the atmosphere

Where is it likely to fall?

To determine whether rainfall is going to be widespread or isolated, we look at the vertical stability of the atmosphere. This is an indication of how high the clouds can grow to.

If the atmosphere is stable this leads to flat, layer-type cloud which typically means large areas of mostly uniform rainfall totals. If the atmosphere is unstable then we get clouds that can be very tall, have gaps between them and produce rainfall that is much more variable in nature.

This type of variable, isolated rainfall is referred to as showers and is usually the reason why one town can receive significant rainfall and another town just 20 km away can get nothing.

You can usually tell to whether to expect showers by looking at the forecast. The rainfall range will be large, for example, 2–15 mm. When the rainfall range shows reasonably large totals but a relatively small range like 15–20 mm, there's usually widespread rain falling from a broadscale cloud system, not just showers or thunderstorms popping up here or there. Read our blog on how to interpret the daily rainfall forecast.

Image: heavy rain over Noonamah, Northern Territory. Credit: Chris Kent Photography

Why rainfall forecasts can sometimes change

Our rainfall forecasts use a combination of computer model output and forecaster intervention. When the forecast is for 4 days or more, there is often no physical evidence on current weather charts of the mechanism predicted to cause the cloud and rain on that day (such as a cold front). At this time scale, forecasters are heavily reliant on the model output, and there may be variations each time the models are run. As newer observations become available to be fed into the models, this can lead to changes in the rainfall forecast. So it's best to check back regularly for the latest updates.

As the timeframe for the forecast becomes shorter, then the rainfall forecasts become more certain, because there's more physical evidence fed into the forecasting process.

The value of the human touch

The isolated nature of thunderstorms poses significant challenges in forecasting the exact locations of where the heaviest rain will fall. In particular, summer storms are notoriously explosive and erratic. At that time of year there's extra heat and energy in the atmosphere. There's also plenty of moisture and instability in summer to fuel the development of showers.

For a thunderstorm to form it needs a trigger, and this is where a human forecaster adds real value. A forecaster has an in-depth understanding of converging winds and local topography, such as surrounding mountains or hills, that can initiate thunderstorm formation. By applying their local knowledge and experience to the model output, forecasters can better reflect likely conditions on the day.

How is rainfall measured?

The standard instrument for measuring rainfall is the 203 mm (8 inch) rain gauge. This is a circular funnel which collects the rain into a graduated and calibrated cylinder. Rainfall is measured to the nearest 0.2 mm. Anything less than this is recorded as a trace.

In modern automatic weather stations a tipping bucket rain gauge is used. These never need to be emptied and allow readings to be sent automatically.

We collect daily observations from approximately 6600 rainfall stations across the country. These rainfall observations not only feed into our forecasting models to predict the weather into the future, but also help strengthen our long-term understanding of Australia's past climate.

More information

Find weather forecasts, including rain information, on our website or on the BOM Weather app.

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.