Severe thunderstorms: your questions answered

10 December 2018

All thunderstorms are pretty severe aren't they? Well no, only some are officially classified as 'severe'. So what exactly sets these storms apart and when are they most likely to happen? You asked and our meteorologists answered these – and lots more – of your storm questions.

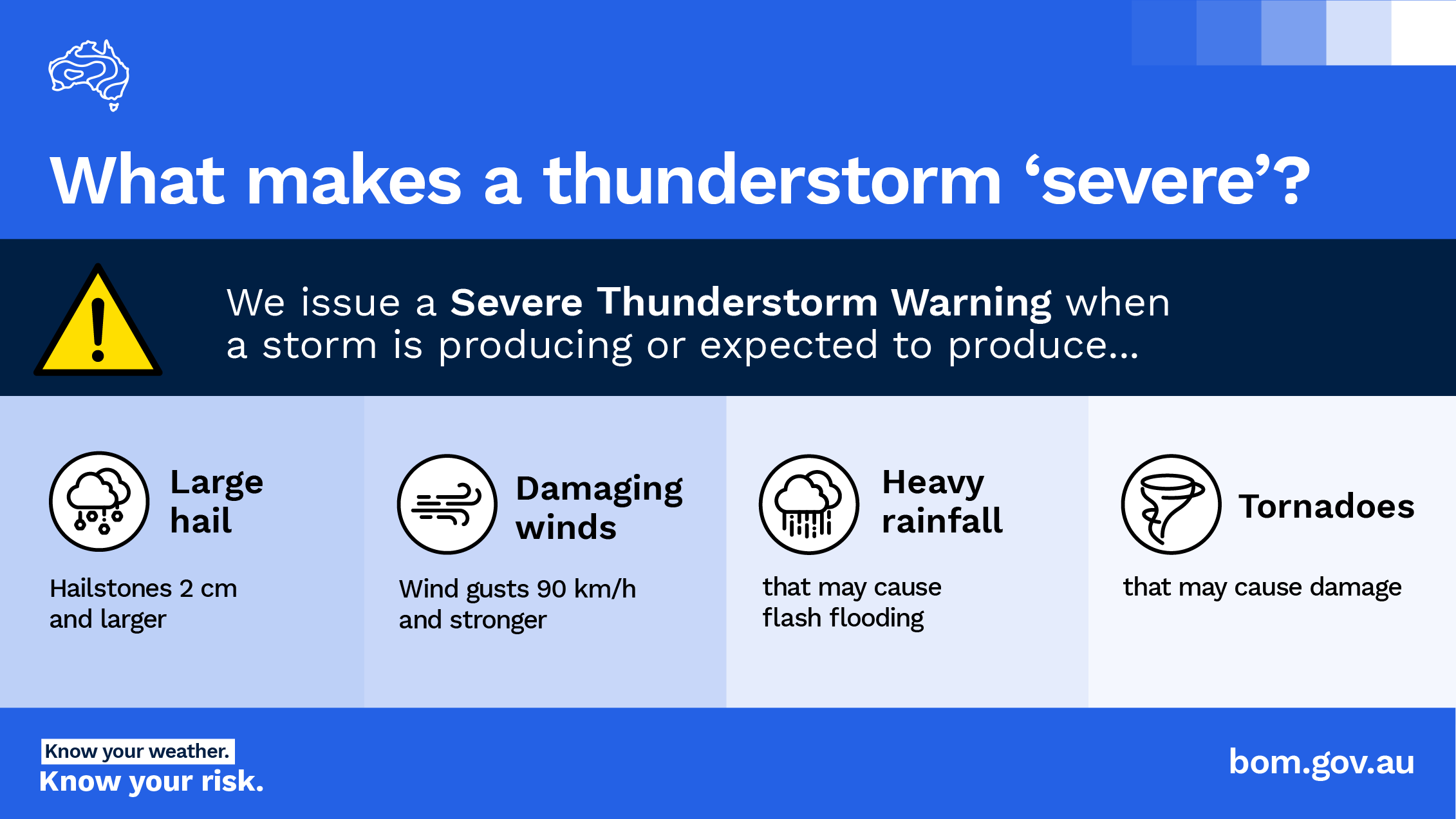

What makes a thunderstorm 'severe'?

We see a lot of thunderstorms with rain, lightning and thunder, but a 'severe' thunderstorm is when we might start seeing those storms cause damage or impacts to people and infrastructure. We classify a thunderstorm as 'severe' if we expect or observe that the storm is producing any of:

- 2 cm hail (about the size of a $2 coin) or larger, which can damage crops and property

- wind gusts of 90 km/h or higher, which can cause damage to vegetation and buildings

- heavy rainfall that could cause flash flooding, for example, flooding roads or creeks

- tornadoes.

It's these potentially damaging thunderstorms for which the Bureau issues Severe Thunderstorm Warnings.

When hail 5 cm across or larger is expected, we add the words 'giant hail' to our warning. National and international studies have shown that hail of that size increases associated damage by several orders of magnitude – mostly because roofing tiles start to break.

When wind gusts reach or exceed 125 km/h, we add the words 'destructive wind gusts' to our warning. We may also include 'intense rainfall that may lead to dangerous and life-threatening flash flooding' for rainfall rates that are unusual for the affected area.

Why doesn't the Bureau warn for lightning?

Every thunderstorm has lightning. Some have more than others, which can make a thunderstorm appear significant or severe but if we warned for lightning would have to issue warnings for every single thunderstorm. While lightning can be dangerous if you're outdoors, our warnings focus on those storms that are more likely to cause damage or other impacts.

Learn more about lightning here.

What is a supercell?

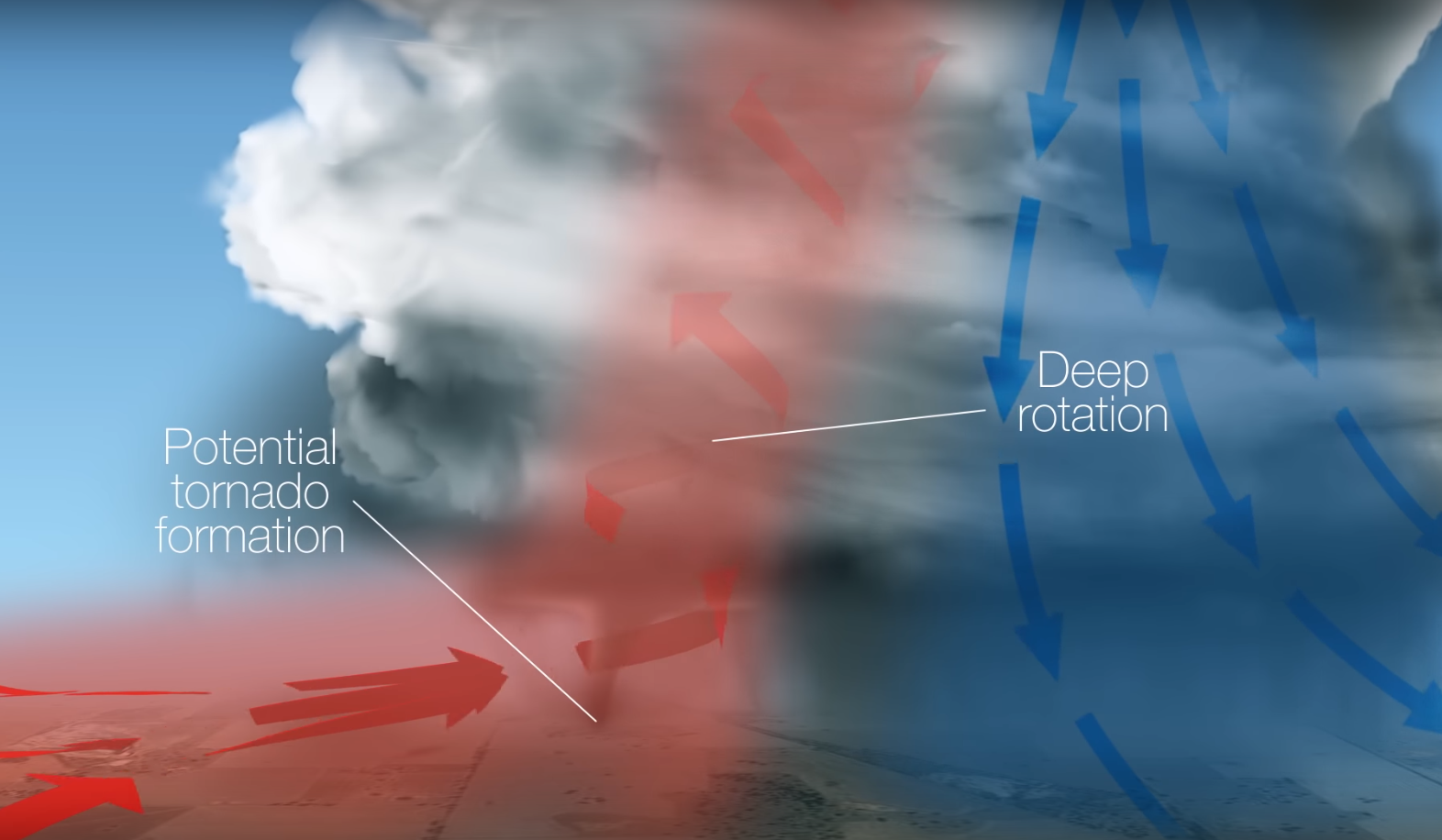

Any thunderstorm requires 3 basic ingredients to form: moisture, a lifting mechanism, and instability in the atmosphere. The addition of a fourth ingredient, wind shear, can organise a thunderstorm into a supercell. Wind shear is the increase in wind speed with height, and the change in wind direction as you move up through the atmosphere. This leads to tilting and rotation of the updraft in a thunderstorm, into a kind of sloping corkscrew structure. This 'organisation' means the cool downdraft is separated from the warm updraft, so you don’t see any of the interference between the two that weakens non-severe thunderstorms.

These organised thunderstorms can last many hours and travel long distances, potentially causing considerable damage. The deep rotating column of air, tilting away from the downdraft, is also what can form tornadoes beneath the storm – see below. So when the Bureau observes or forecasts conditions that support deep rotation and separation of updrafts and downdrafts in storms, we may issue Severe Thunderstorm Warnings.

Non-supercell thunderstorms can also produce some of the dangerous effects listed above, such as damaging winds and flash flooding, albeit for shorter periods. Whenever such hazards are observed in a storm, we consider it 'severe' and issue warnings.

What causes storms to split?

Severe thunderstorms can 'split' due to the influence of strong vertical wind shear, which the change in speed and direction of the wind as you move from the ground/surface higher up into the atmosphere (see above). This can cause the top of the storm to move in one direction (with upper-level winds) while the base of the storm moves in another direction (with winds closer to the ground). A vertical pressure gradient is set up, causing a strong upward force within the storm. Either side of this upward force, 2 separate updrafts develop and move away from one another, becoming 2 separate storms.

Do we get tornadoes like in the USA?

Australia does see around 30 to 80 tornadoes per year, but most of them are in areas with very low population. If there's no-one around to see it, we don't get a report of a tornado. They can't be identified from satellite imagery, as they're underneath clouds.

Australia has had some significant tornadoes (those rated as 2 and above on the enhanced Fujita scale) including:

- an F4 (Fujita scale 4) tornado in Bucca, Queensland, in the early 1990s

- an F3 tornado in Mulwala, Victoria, in March 2013.

The USA, due to different atmospheric conditions, sees around 1200 tornadoes per year. Of these, one or 2 might be rated EF5 on the enhanced Fujita scale. There's also a much larger population there to photograph and report the tornadoes that do form.

What turns a thunderstorm into a hailstorm?

In any type of thunderstorm, there is likely hail well above the ground (5–7 km up), but most of it melts as it falls and reaches the ground as rain. In a more 'organised' thunderstorm, stronger updrafts hold more rain and hail above the 'freezing level' (the height at which rain starts to freeze) for longer. This allows freezing rain to clump together into larger and larger hailstones. Read more in our Explainer: how hail forms.

Do we get hail in the tropics?

It is quite rare to hear reports of hail in Darwin, for example, and when it does occur it's very small. The freezing level is the height above which raindrops in a cloud start to freeze and form hail (see above). In southern Australia, that's usually around 3–4 km up. In the tropics it's around 5–6 km up, giving hail much more time and air to pass through before it reaches the ground, so it mostly melts and falls as rain.

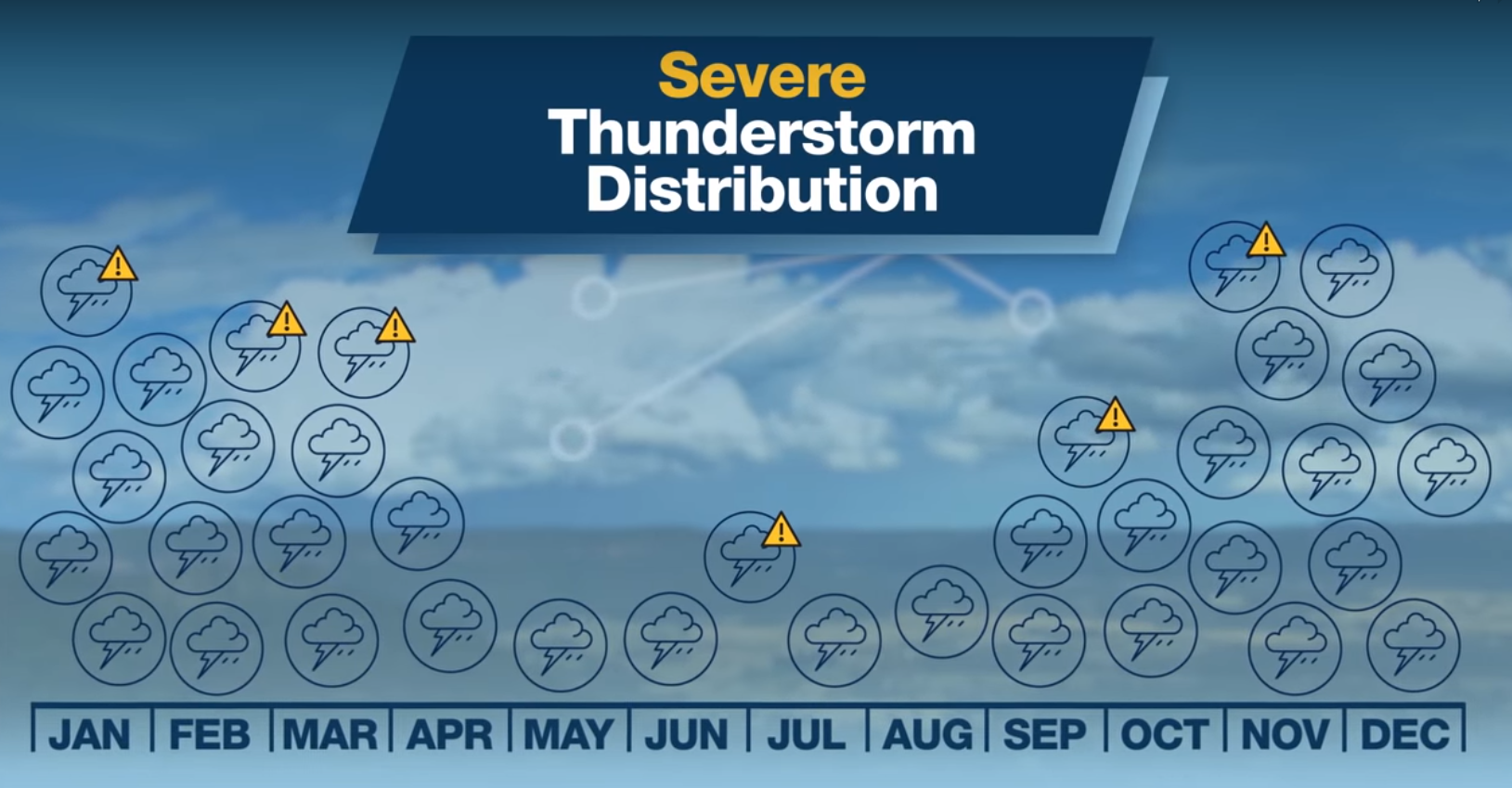

What time of year do we normally see the most severe thunderstorms in Australia?

The warmer months from September to March are the peak season for severe thunderstorms, due to the added warmth and moisture in the air. We can get severe thunderstorms in the cooler months, though, mostly connected to cold fronts that cross southern parts of Australia.

Are thunderstorms in Australia becoming more severe or more frequent?

Consistent with global studies, an increase in the proportion of heavy rainfall has been detected over Australia. Since the 1970s, we've seen an increase in how much of Australia receives more than 90% of its annual rainfall in the form of 'extreme rain days'. That is, days in the top 10% of 24-hour rainfall totals. Read more on the Climate Change in Australia website.

Does the colour of storm clouds say anything about what type of storm it is?

The colours seen in thunderstorm clouds depend on the ice content in the clouds, but also on the angle of the sun and how the sunlight penetrates the storm. Storm clouds generally appear dark blue or black, but sometimes you can see brown, green or red tinges:

Clouds can appear brown before a storm, particularly in the interior of Australia, when the updraft has picked up a lot of dust from the ground. That dust or dirt in the air can provide the 'nuclei' onto which water vapour condenses to form cloud, raindrops and hailstones.

The reason some thunderstorms appear green is still the subject of debate, but it seems that the green component of sunlight is scattered preferentially in stronger thunderstorms that contain large amounts of hail and/or larger hailstones – and perhaps also water droplets. It’s widely believed, and supported by anecdotal evidence, that the eerie green glow requires the presence of hail in the storm. But that doesn’t necessarily mean the storm will deliver hail on the ground (see above).

Early and late in the day, the sun's rays have travelled through more atmosphere and had more of their blue and green wavelengths scattered before they reach clouds, so it's mostly orange and red light that reflects off clouds around sunset and sunrise.

Do fish really fall from the sky in some storms?

It can happen! When tornadoes in a thunderstorm form over water (known as a waterspout) or briefly cross a pond or lake, they can pick up a lot of water – and along with it, some small marine life such as frogs and small fish. These can be carried for some distance in the storm, depending on the strength of the updrafts.

More information

- As part of our AskBOM video series, most of the questions answered in this article were asked by our Facebook community at this live Q&A.

- Stay up to date with weather warnings

- Severe thunderstorm knowledge centre

- AskBOM: what is a thunderstorm?

- Clouds: your questions answered

- Explainer: how does hail form?

- Explainer: what is thunder?

- A bolt from the blue: what is lightning?

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.